[This article contains major spoilers.]

Being human is a real horror show.

We’re all just a bloody mess of feelings and needs, inhabiting dumb bodies full of organs with their own ideas—competing, and often conflicting, with one another. Head and heart. Gut and groin. Or, to state it even more plainly: “You can decide who you wanna love, but not who you wanna screw. Attraction’s out of our control; it ain’t healthy keeping those feelings locked away inside.”

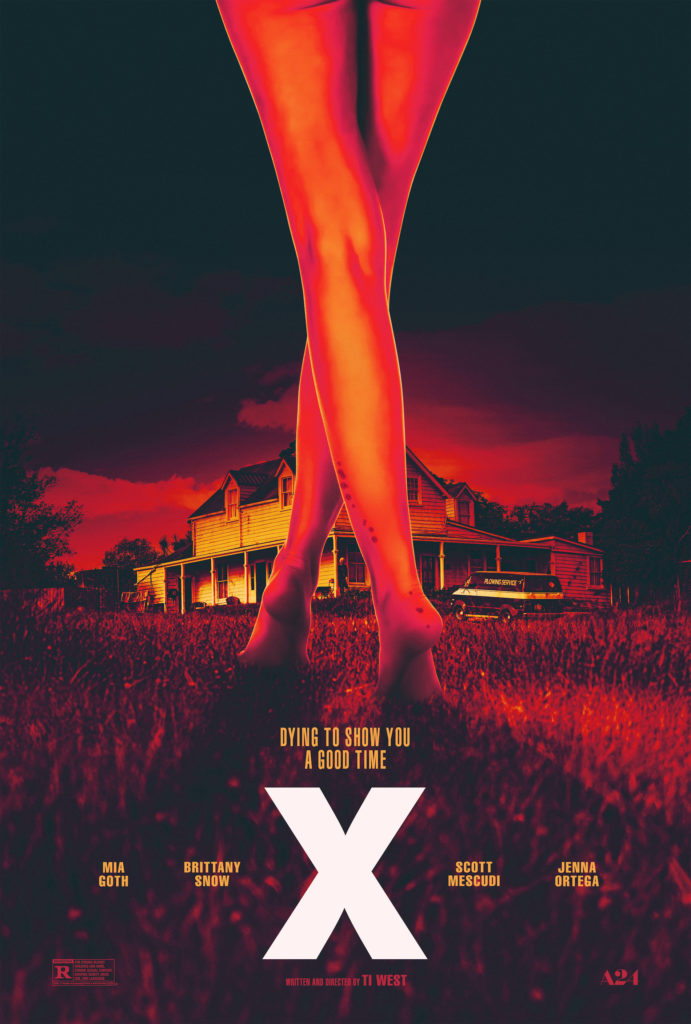

So says Maxine, the heroine of Ti West’s newest horror film, X (2022), a 1970s grindhouse-style slasher that captures the decade both visually and thematically, with plenty of nods to horror movies of the time (THE TEXAS CHAIN SAW MASSACRE (1974) in particular), and a rebellious spirit worthy of taking place in 1979, smack during the Golden Age of Porn. Hoping to get rich on the cusp of what producer Wayne (rightfully) predicts will be the “explosion” of the home video market by shooting a porn film on a bare-bones budget, Wayne and his cohort of performers rent a guest house on a farm for a few days. Wayne does not inform Howard, the cantankerous property owner, of what the crew intends to do on his property, however. His philosophy? “Better to ask forgiveness than permission.”

The crew consists of a likeable gang of scrappy amateurs: Wayne, the genial patriarch of sorts who dispenses advice as easily as jokes; Bobby-Lynne, a convivial actress who wants to become famous enough to “tan her titties” in her own pool; the supremely confident Jackson (the only male performer, and a former Marine); RJ, a writer and videographer who is at turns pretentious and insecure about his work; his girlfriend Lorraine, a reluctant assistant to the shoot; and finally, Maxine Minx, Wayne’s girlfriend and a self-described sex symbol.

It’s all sex and young, uninhibited fun, except for one wild card: Howard’s wife, Pearl, a frail old woman who wanders the property with a cloud of white hair and a beckoning hand.

While the others get busy shooting the first sex scene of the film (a lively romp between Bobby-Lynne, playing a farmer’s daughter, and Jackson, a wayfaring stranger), Maxine meanders to the nearby water for a swim. There does seem to be something special about Maxine, who complains of her cosmopolitan tastes not being met and her need to be famous now, something that keeps her both coveted and protected. In an almost mystical way, her ethereal beauty seems to shield her from the dangers of life itself. While taking a swim, for example, she is unwittingly stalked by a crocodile, only pulling herself onto the safety of the dock moments before it reaches her. She walks away, unaffected.

Pearl also takes a particular shine to Maxine, and lures the young woman into her home with a glass of lemonade. Once inside, Pearl haltingly tells Maxine a truncated version of her life, one in which she was a beautiful dancer with a husband—Howard, though an old photo shows how much time has worn on them both, and earlier dialogue suggests that he can no longer satisfy his wife’s sexual needs—who would “do anything for [her] back then.” But, “not everything in life turns out like you’d expect,” Pearl concludes in a voice aching with remorse.

Turning her attention back to Maxine, Pearl’s hunger for the younger woman’s youth and beauty, for Maxine herself, is immediately apparent. In a few moments intercut with the sex scene between Bobby-Lynne and Jackson, Pearl reaches towards Maxine’s exposed side and runs a finger along her skin. “It’ll be our little secret,” she says cryptically as Maxine makes her exit.

When Maxine shoots a scene with Jackson in the barn, we again witness the unique power of her allure. As she moans and writhes, seductive and snakelike atop Jackson, there’s awe in his expression. Likewise, Lorraine, who called the production “smut” only hours earlier, dons a look of newfound curiosity, maybe even respect. And peeking in through a window to watch the entire production is Pearl, imagining herself in Maxine’s place.

In this scene and so many others, X deftly explores the ways people relate to sex—the baggage and shame we carry around our sexual selves, as well as the many ways sex can be healthy and therapeutic, even transformative. It can also expose some of our worst impulses and deepest insecurities.

After concluding the first day’s shoot, Lorraine questions the other two women about their profession, and Bobby-Lynne explains her decision to do porn: “Queer, straight, black, white, it’s all disco. You know why? Because someday, we’re gonna be too old to fuck. And life’s too short, if you ask me.” Maxine is a smidge more eloquent, and in a “toast to the perverts” who pay their bills, she neatly summarizes her mentality: “To living life on our own terms, and never accepting what self-righteous naysayers have to say.”

Bobby-Lynne and Maxine are also quick to reach the crux of the issue: “We turn people on, and that scares ’em,” Bobby-Lynne tells Lorraine. “And they can’t look away, neither,” adds Maxine. Therein lies the rub; most of us want sex but are conditioned by society to be terrified of it. To look away even when we’re enjoying what we see, and to feel guilty when we give in.

Apparently inspired by the conversation, Lorraine confesses to the group that she wants to be in the movie. RJ, a stand-in for insecure guys everywhere, makes an instant about-face. Although earlier in the day he berated his girlfriend for being a “prude” due to her discomfort shooting sex scenes, his distress at the idea of her actually participating in one is evident. Vacillating between condescension and irritation (a tactic he employs on Lorraine throughout the film), he tells her she can’t possibly be in the film because it wouldn’t work with the plot.

RJ chose the wrong crowd for that kind of reasoning, though, and Lorraine points out that no one watches a porno for the plot – they come to see “tits and ass, and a big dick.”

The owner of said phallus, Jackson, is RJ’s obvious foil. A man so self-assured that he takes it in stride when Bobby-Lynne tells him she faked her orgasm during their scene together (“It’s called actin’!”), Jackson actually lives out the bohemian ideals of free love and no judgment that RJ can only pretend to inhabit. Jackson has an open relationship with “sometimes”-girlfriend Bobby-Lynne, and he agrees with Wayne that the presence of a camera makes things all business, nothing more.

Wayne himself is somewhere in the middle, permissive of Maxine’s career (insomuch as he hopes she’ll make him rich) but still holding his own sexist views of women. When RJ storms off over Lorraine’s decision to be in the film, lamenting the fact that she’s a “nice girl,” Wayne tells him, “Ain’t none of them nice girls.”

X is not concerned solely with our relationship to sex, but also with the inevitable intersection between our aging bodies and the desires that can outlast those bodies. As a moving rendition of the song “Landslide” sung by Bobby-Lynne reminds us, this film is concerned with examining all the phases of life. About halfway into X, our main characters, in all their glory and aggressive libidos, finally collide with Pearl and her pent-up appetites.

While Lorraine is shooting her scene, RJ decides to drive off in the middle of the night and leave the entire crew behind in order to teach Lorraine the lesson he thinks she deserves. He’s stopped on his way out by Pearl, who begins shedding her clothing and begging to show RJ what she’s “capable of.” Unfortunately, RJ is not the least bit interested in what the strange old woman is capable of, and he says as much, repulsion etched into his face.

Unable to sate her all-consuming needs through sexual intercourse, Pearl instead penetrates RJ with a knife, stabbing him over and over again, rubbing his blood up and down her arms sensually. The murder is visceral, sexual, and deeply uncomfortable—but the cathartic act transforms Pearl. As she gazes at the blood on her hands, she’s momentarily transported, her arms lilting and floating in the air as she begins an eerie, graceful dance. The moment is shockingly poignant as we get a small glimpse of the woman Pearl once was.

Pearl and Howard go on to kill the rest of the crew—by shotgun, crocodile, and various other methods, none of them nearly as sexually charged as RJ’s death—except for Maxine. In a bit of pointed irony, Pearl and Howard continually admonish the performers for being “whores” and “deviants,” all while seeking out the very same pleasures as their younger counterparts, as well as far more transgressive ones.

Once again, Maxine’s exceptional youth and beauty save her—for the time being, anyway. Although Pearl sneaks into Maxine’s bed and caresses the woman’s naked body enviously, she doesn’t hurt her. It’s almost as if she can’t bear to disfigure someone so perfect, someone who reminds Pearl so much of herself back when she was a “beauty,” and so she simply marks Maxine’s body as hers by painting the woman in blood. Ultimately, Maxine gets away physically unharmed.

The murders unleash something in the couple, and Howard gains the ability to have sex with his wife for the first time in ages. “Tell me I’m yours. That you still want me. Make me feel young again,” pleads Pearl, succinctly encompassing all that sex can be, and mean, and how excruciatingly we feel its loss. Not only the loss of sex, but of connection to another person, and the sense of self-worth that comes with a satisfying relationship.

In the end, it’s almost a tragic irony that Pearl and Howard find one another again, only to be brought down by their own crumbling bodies: Howard succumbs to a simple heart attack, and Pearl is overcome by a broken hip caused from using her own shotgun. As Maxine drives away, Pearl shouts after her, “You’re not special. It’ll all be taken from you!”

She might be right. Time robs us all of our charms, eventually. Throughout X, however, Maxine repeats a mantra to herself: “I will not accept a life I do not deserve.” We hear this same chant emanating from dimly-lit TV screens haunting the backgrounds of multiple scenes: In the convenience store, accompanying the judgmental but curious stare of the clerk; playing ad nauseum inside Pearl and Howard’s house. It’s a televangelist program, spouting hypocrisies about the power of Satan and the evils of the degenerates and whores supposedly forcing their ways upon polite society.

At the end of the film, it’s revealed that Maxine is the daughter of that same televangelist, and that she has perverted his mandate, “I will not accept a life I do not deserve,” into something self-empowering rather than oppressive. She proves throughout X that she’s already living according to her own principles. Perhaps it’s not just Maxine’s beauty, but her faith in herself, and her unshakable belief in her right to happiness and a good life, that has kept her thriving for so long.

Beauty can feel like a superpower, like a bubble of protection in a harsh world. But it’s a double-edged sword when everyone wants you, and then one day, suddenly, they don’t. Sometimes the things you were protected from become different, even bigger, problems. With Pearl’s youth and beauty also went her sense of self, and all she was left with was regret for the things she didn’t do. X leaves us to ponder if Maxine will manage to avoid the same fate.

If you ask me? I have hope for her.

Tags: A24, Brittany Snow, Chelsea Wolfe, David Kashevaroff, Eliot Rockett, Horror, James Gaylyn, Jenna Ortega, Kid Cudi, Martin Henderson, Mia Goth, Owen Campbell, Scott Mescudi, Stephen Ure, Ti West, Tyler Bates

No Comments