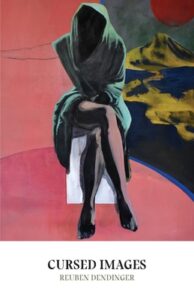

Maybe you’ve heard, but horror is having a bit of a moment. For whatever reason, as the world has grown darker and scarier in recent years, and all available news coverage has grown darker and scarier in covering it, our collective desire for even darker, scarier entertainment has quite noticeably increased right along with. There are any number of theories as to why this is. Maybe we need to feel validated in our increasing existential dread. Maybe we need to be reminded that, however bad things seem, the worst we can imagine is still (mostly) fiction. But whether it’s catharsis or reassurance we’re after, one thing is clear: horror isn’t just for weirdos anymore. It’s a diversified portfolio. A labyrinthine catacomb of subterranean subgenres. From cozy to comedic to cosmic, political to philosophical to psychological, body to transgressive to splatterpunk, it’s a big spooky tent full of killer klowns and carny contortionists and virtually everyone you know is buying some version of the ticket and taking some version of the ride.

And yet, somehow, Reuben Dendinger is still doing something a little different. From all of that.

The stories in Cursed Images feel… not “out of time” exactly – they are all pretty clearly tied to our present moment – but rather more like they expect to be anthologized, read, and even taught somewhere down the line, and it’s their duty to represent the miasmic unease of said moment accurately, for canonical posterity. Where so much modern horror is indebted (often to the point of insolvency) to Stephen King and the slasherific 80’s, Dendinger’s work seems inclined to skip over that done-to-death era, as well as the next six to ten, until he’s rubbing elbow patches with the likes of Robert W. Chambers and Edgar Allan Poe. In his depressive trust fund kids, aimless radicals, and myopic hipster artists we see the mad aristocrats, haunted soldiers, and hopeless romantic poets of yore, as well as the deathly cyclical nature of the human experience on doomed repeat. Only the sets and costumes have changed (and even those not all that much).

In the powerhouse opener, The Brooms of Carlack, an idly rich young man seeks out his long-lost sister and her critically reviled, psychologically destabilizing artwork. Whether she’s in league with the devil, or just running a long con for the ages, is largely left up to the reader to decide. In the brief I Am Looking for a Very Specific Video an unnamed narrator gives voice to the dark side of media obsession, repeatedly trying and failing to explain himself in direct address to the reader. A complete cipher, he could be anyone from an anonymous YouTube comments section poster to a lonely cinephile at a video store to a shifty-eyed seeker of illegal pornography, but in our age of constant feed-fed screen saturation, the larger point might be that that dubious spectrum now includes all of us.

Xibalba(R) feels like something of a thesis statement as it traces the rise of SCAD, or Social Collapse Anxiety Disorder (and also, in what I’m guessing is a bit of a winky joke, the Savannah College of Art and Design – the kind of splashy institution that spits out the kind of characters Dendinger writes about in droves). Essentially the pervasive angst of the 21st century writ diagnosable, SCAD presents as an extreme, often suicidal depression afflicting the fearful, futureless young, and the titular drug its suppose cure. In charting the effects of mass inoculation on the populace, Dendinger builds a world of metaphor for all those aforementioned theories on the exponential rise of popular horror, and raises fascinating questions as to whether the balms of escapist desensitization and, increasingly, collective shrug nihilism are really worth the price of alleviating our fears.

Despite these heavy themes, there’s a certain wry levity that animates many of Cursed Images‘s best stories. The absurdist The Real Simon Dick follows a group of wannabe radicals who find themselves unable to shake a semi-famous neo-Nazi clinging to their social circle, seemingly out of little more than garden variety loneliness. Reminiscent of that hilarious viral video of Richard Spencer getting punched in the face, it’s by far the funniest and most bizarre story in the collection, and serves as a welcome reminder that even the most theoretically terrifying bogeymen often prove little more than toothless nuisances in practice.

Finally, in a neat bookend with the opener, the lengthy piece de resistance Milo’s Commute explores, via a deep dive into the sadboi ethos (a type the book pokes oodles of fun at throughout), one man’s descent into full-on psychosis as he struggles to rectify his own dangerous artistic ambitions with his heartbreak and sexual hangups. Going through a bad breakup with a woman who has already moved on in spectacular fashion, Milo throws himself into his work in a way he’s never managed before, effectively Kübler-Rossing himself through his lowest point toward results that could either destroy or resurrect his entire life. And in the end, just as with the crazy-making paintings from The Brooms of Carlack, art, and sanity, are very much in the eye of the beholder.

If I were to use one word to describe Dendinger’s style, it would probably be “disciplined.” These are taut, sinewy tales of the macabre without an ounce of fat on their sacramental bones. Indeed, as its title suggests, the stories in Cursed Images often feel like meditations on a specific focus object. A broom. A video tape. A train engine. A skull. They bloom outward like tendrils of sentient smoke, and tickle your brain via every orifice – infecting you, healing you, and yes, possibly even cursing you with their ominously comfortable gloom; their vaguely hopeful despair. He writes about dark magic and the occult in such a matter-of-fact way, seamlessly integrating the real and the surreal, that one finds it easier than usual to believe such things might actually be influencing the world today; that ghosts and necromancers and succubi might well be walking among us right now; that perhaps it is the artists, in all their self-serious, self-conscious, self-centered mania, that keep them alive, embodying our old world fears for all our new world sakes. After all, we’re all afraid of something these days. It’s the nature of our big tent horror times. We may as well keep our options open as to which fears we dwell on; what darkness we let in.

-Dave Fitzgerald

No Comments