True crime has historically focused on middle-class and wealthy white women. Examining crime statistics in the US, one sees that queer people, women and men of color, trans people, sex workers, and the homeless are at substantially more risk than white women of means. True crime, and drama based on true crime, in its most exploitative form, will often trade on the myth that it’s some kind of quasi-educational service to society. Drama based on real crime, in my estimation, is best when it forgoes the notion that it’s any kind of public service. It’s best when it looks at the society that demands these stories. David Fincher’s ZODIAC is less a tale of the Zodiac Killer and more an examination of the cost of obsession. Spike Lee’s SUMMER OF SAM is about the cultural permissiveness and leftism of the 1970s reaching a breaking point and the American desire for paranoia and scapegoats.

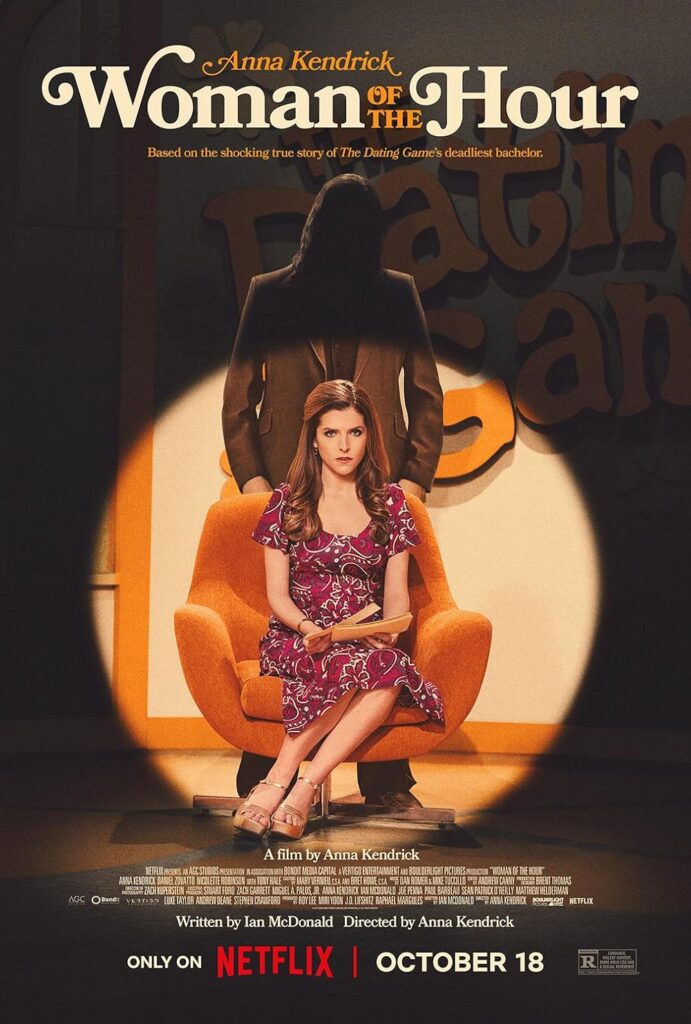

Anna Kendrick’s WOMAN OF THE HOUR belongs in the conversation with Fincher and Lee’s work. I watched the film twice in preparing this and devoured every interview with Kendrick I could find on the film. When speaking with Deadline, she spoke about her internal conflict about taking on directing: “…it was a thought that I was actively shoving down, and I guess it would no longer be silent.” We’re better for her no longer being able to tamp down those thoughts.

Kendrick uses WOMAN OF THE HOUR to comment on the cruel cultural reality that women are observed, they’re watched, but they’re never heard. Kendrick and screenwriter Ian McDonald populate their story with a variety of shitty men whose first instincts are to possess, commodify, and ignore the women that surround them. When we meet Sheryl Bradshaw (Anna Kendrick, pulling double duty), she’s at an audition where casting directors are casually discussing and dissecting the qualities of her body. When they dismissively ask if she’s willing to do nudity, they respond by assuming her refusal must be rooted in shame. Tony Hale, in a particularly great and slimy performance, plays the host of The Dating Game. He has Kendrick’s character re-costumed without consent, repeatedly touches her without consent and tells her to pretend to be stupid to coddle the bachelors.

The film orbits around killer Rodney Alcala (Daniel Zovatto) between 1971 and 1979, shuffling back and forth in time. Often a shuffled chronology is simply narrative sleight-of-hand used to disguise thematic flimsiness. (I’m looking at you, STRANGE DARLING.) Kendrick and McDonald use shuffled chronology here to show a dance of intimacy between Alcala and his victims. The film is explicit in stating the truth that every time a woman offers trust, she’s making herself vulnerable, and much of day-to-day to life is managing and placating male egos to stay safe.

The film opens in the Mojave Desert, where Alcala is photographing his intended victim. The sky is filled with rolling clouds and swirling hues of pinks and blues. The terrain is covered with rough texture, craggy alien shapes, and hungry Joshua Trees. It’s within a natural mise-en-scène worthy of Andrea Arnold that Alcala’s victim opens up to him. She tells him about a miscarriage and a broken relationship. She laments that trust is always a risk. Then the camera backs up to a wide shot, framed from inside the car that brought them there. The car’s window forms a television-like frame around Alcala’s murder. Kendrick is explicit here: The violation of women’s trust and the violence that follows is perceived as entertainment.

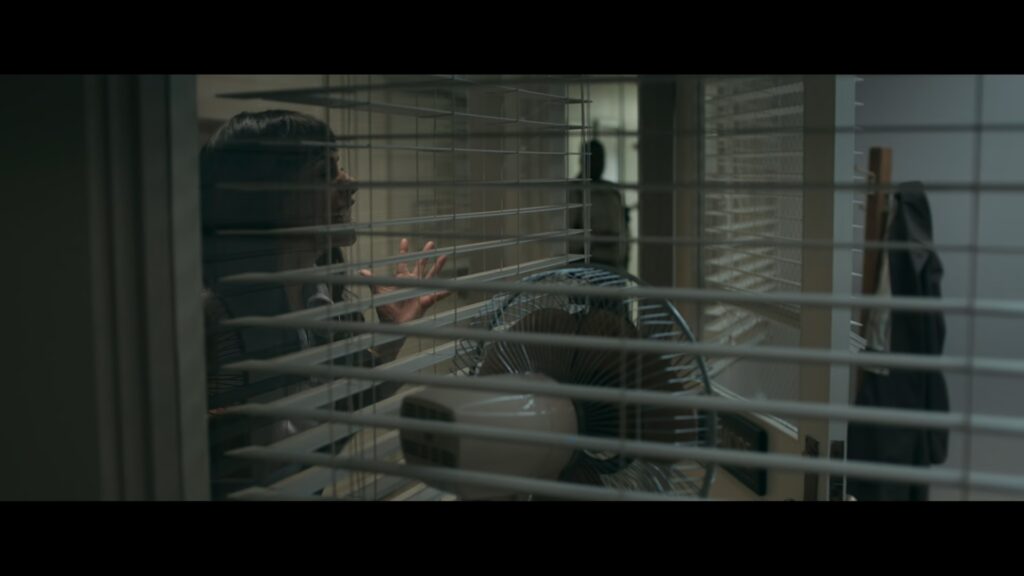

Kendrick returns to the TV-like framing around her female characters throughout the film. Whether it’s peering through windows or looking in mirrors, Kendrick finds frequent reasons to be framed in TV-like rectangles. Sheryl Bradshaw may be on The Dating Game, dangled in front of a serial killer, but women have to perform every day.

Kendrick finds fascinating ways of drawing further attention to this television-like frame. When Laura (Nicolette Robinson) is at a police station begging for someone to follow-up on her identification of Alcala, her final moment of frustrated horror frames her through a window as she beats on it, begging for a cop to do his job.

The final leg of the film follows a homeless runaway, a member of one of those marginalized groups I mentioned earlier. Amy (Autumn Best) is a version of the runaway that eventually led to Alcala’s capture. After she’s placated his ego by asking him to keep his assault of her a secret, they walk back from a desert clearing to his car. The camera patiently pushes in as they get into Alcala’s car, following Alcala as he climbs into the driver’s seat. When he slams the door, our angle on his driver’s-side rear-view window reveals Amy filling it as if she was posed on a television.

Shortly thereafter, they’re idling at a four-way stop, and she locks eyes with a driver in another car. Her face is a portrait of desperation. The other driver, a man, drives off without a second thought. Women are watched, but never heard.

The more said about Zach Kuperstein’s excellent cinematography, the better. Kuperstein shot BARBARIAN, THE EYES OF MY MOTHER, and THE VIGIL. Here though, the guiding voice seems more assured and more confident in what they want to accomplish. Last year, Matt Ruskin directed BOSTON STRANGLER for 20th Century. All Ruskin was able to do was ape the work of Ridley Scott and David Fincher without examining why those filmmakers maker their choices. It left BOSTON STRANGLER, another true-crime drama focused on women, feeling like an aesthetic exercise. If someone glances up from Instagram, they might mistake it for ZODIAC.

Kuperstein understands that Kendrick is using the natural world to reinforce the tragedy of the situation and increasingly smaller rectangular frames to show how women are trapped and observed by a violent paternalistic society. The camera skulks and follows; it emphasizes a sense of the viewer’s own inaction. After Bradshaw and Alcala finally cross paths on The Dating Game, they go for drinks. Once she’s creeped out, she responds to his request for her telephone number by giving him a fake number. Alcala, realizing she’s shaken free of him, stalks her across the parking lot. It’s evident he plans to kill her. The camera dollys slowly, matching their pace. We feel the voyeurism of our own observation. When Alcala finally retreats into the night, it’s because a nearby factory has an end-of-shift, and men start pouring out of its doors within eyeshot, all deftly shot to bring the point home.

Despite its grim subject matter, WOMAN OF THE HOUR is not entirely without hope. Amy is able to escape Alcala, which leads to his arrest, and Sheryl ultimately escapes Hollywood. Three times in the film, men buck the reinforcement and permissiveness of rape culture. Laura’s boyfriend realizes he was wrong to doubt her account and then accompanies her to the police station. A custodian at the TV studio realizes Laura has been tricked into waiting for help that will never come and then offers to help her. From The Dating Game itself, Bachelor Number Two warns Sheryl about Alcala after he realizes how dangerous Alcala is. None of these moments are perfect, but they suggest that as soon as a man realizes he is actively contributing to a culture of danger, he can self-inventory and start the work of dismantling it.

This is a true-crime drama that bounced around for years and originally had an entirely different director, Chloe Okuno, attached. When it finally went into production, it was with a first-time director who was an actor. One would be right to not expect much. That’s why it’s so exciting that Kendrick’s voice is so assured and the film shows so much promise. Expect names to flash through your mind as you watch in the form of Kendrick’s obvious influences, but don’t make the mistake of leaving it there. What she has to say is all her own, and WOMAN OF THE HOUR is a near-perfect opening statement.

Tags: Andrew Canny, Anna Kendrick, Autumn Best, Dan Romer, Daniel Zovatto, Ian McDonald, Mike Tuccillo, Netflix, Nicolette Robinson, The 1970s, Tony Hale, true crime, Zach Kuperstein

No Comments