Happy All-Hallow’s Month! In anticipation of Halloween — which, let’s face it, we’ve been anticipating since last Halloween — Daily Grindhouse will again be offering daily celebrations of horror movies here on our site. This October’s theme is horror sequels — the good, the bad, the really bad, and the unfairly unappreciated. We’re calling it SCREAMQUELS!

And if you like this feature, please check us out on Patreon for unique reads and deep dives! Just $3 a month gets you everything! All treats, no tricks.

Christmas horror flicks have always had a mysterious appeal to me. Maybe it’s the juxtaposition of what is often referred to as the happiest time of the year being the setting for horrific events that makes this special little subgenre sing for me. And if all great horror subgenres have at least one franchise to hang their hat on, Christmas horror flicks have one of the oddest: the SILENT NIGHT, DEADLY NIGHT series. What began as a sort of rote exercise in recreating such holiday slash-ics as HALLOWEEN and FRIDAY THE 13TH quickly became mired in controversy; parents picketed the theaters showing the original 1984 release for “demonizing Santa Claus” (hard to imagine today) until it was pulled in about a week. It received a fractured new theatrical run about a year later, but that was financially unsuccessful. And for a while, that seemed to be it for this Santa slasher.

But then, in 1987, PART TWO was released. A far campier tale of a Santa Claus killer, this film is probably best remembered for its iconic “Garbage Day!” that the killer shouts before shooting a trash collector. For this sequel, efforts were made to connect it to the original, focusing on the brother of the original film’s villain and using about forty minutes of footage from the original re-edited (a classic cheap-out horror sequel technique). By the third film, subtitled BETTER WATCH OUT!, this premise had become something to work around, where the killer from the first film awakens from a coma to stalk a psychic teen. This is easily the worst film in the series, a lifeless re-treading of the first two films, and marks when the series becomes straight to video. But after comes something truly special.

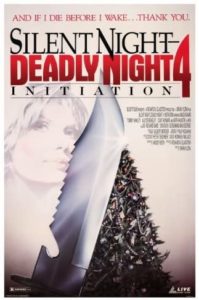

SILENT NIGHT, DEADLY NIGHT 4: INITIATION (1990) is very much the HALLOWEEN III: SEASON OF THE WITCH of this franchise. Both take bold swings after previous series entries felt a little too much like the same ol’ thing again. And both take a slightly meta look at the franchise, showing characters watching the original films that started the whole she-bang. What both films so wisely do is take the franchise to a new genre of horror: while HALLOWEEN III adds a folk horror element to the world of those films, INITIATION shifts things to a body horror arena. This is to the credit of new-comer director to the series, Brian Yuzna, famous for his work on body horror classics like RE-ANIMATOR and SOCIETY. This film, his third feature, feels right at home with that body of work, known for stretching flesh and queer subtext.

And there’s plenty of both in INITIATION. The plot follows Kim, a young woman working at a newspaper and trying to work her way up to reporter. Part of this journey involves sleeping with Hank, a veteran at the job, in hopes that he’ll use his status to elevate hers. Her job position isn’t the only thing weighing on Kim; as an atheistic Jew, the Christmas season exasperates her and makes her feel like an outsider. And now, there’s a news story going around about a woman who spontaneously combusted and fell off the top of a building. Kim isn’t sure quite why she’s so drawn to this story, though part of it certainly could be hearing the way her male co-workers sexualize the dead woman and a desire to treat her better. However, the story is instead assigned to Hank, despite him telling Kim he doesn’t think there’s much there.

Kim isn’t content to let Hank or her boss dictate who tells this story and begins investigating herself. Her nose leads her to the bookstore at the ground floor of the building where the fiery death occurred. There she meets Fima, the eccentric owner with an interest in the occult. It seems she has quite an interest in Kim too, and invites the would-be reporter to a picnic she’s throwing with some friends who she suggests may have information about the dead girl. Kim attends a Christmas Eve at Hank’s parent’s house that night where she is further alienated, first by his father who insists the word of the Bible is literal and must be interpreted as such, and then by Hank himself for not defending her against any patriarchal force, be it his father or boss. In this raw emotional state, Kim attends Fima’s picnic the next day, where she and her two compatriots begin to tell Kim about their “society”, a feminist organization that promotes sisterhood against masculinity. And then Fima kisses Kim, gently on the lips, but with a sensuality.

Suddenly, it’s clear that this is a group of lesbians looking for a new member. Fima has all the energy and mannerisms of a mommy dom, stroking Kim’s hands and kissing her face gently. She confides in Kim that she had a daughter who was pushed away by the father, and this hole in her life she wants to fill with Kim. Kim seems confused by these flirtations, admitting in a telling scene that she feels something missing when she has sex with Hank. But the absolution of this cult keeps her at a distance as well. And she is already so isolated in this world, between her gender keeping her from being taken seriously at her job and her religious identity keeping her at odds with the world during Christmastime. Her heterosexuality is the last thread clinging her to mainstream society and now a charismatic cult mommy has started to threaten that.

Around the time Kim first meets Fima, she begins seeing bugs everywhere. We as an audience are introduced to the bug motif in the very opening of the film, where we see Clint Howard as a homeless man eat a burger encrusted in ants. What feels like just an early gross out, however, is actually setting up the main avenue of horror in this feature. Fima’s cult isn’t just about women, as it turns out, it is also about bugs. In perhaps the most crucial scene in the film, Fima lines up their lesbian cult philosophy to Kim, saying “I bet you and Hank have great sex. And yet when it’s over, you have the feeling that something is missing? There is this parasitic quality to men”. Fima wants this parasitic quality to become impossible to divorce from men physically; she plans to slowly but surely morph the world’s population of men into bugs.

It’s a little hard to argue with her logic when presented with the men in the film. Every single one harasses Kim in a manner of ways: demeaning her job, sexuality, gender, and religion or attempting to bring her into their world of sexism. One man she interviews about the charred up corpse theorizes that she was a sex worker, apropos of nothing, and seems to want Kim to agree with his presumption. Clint Howard’s homeless man Ricky shows that gender-based harassment doesn’t need to come from a place of power, men from all walks of life will take an opportunity to make a woman feel small.

Yuzna paints the sexist world of men very broadly and overtly, but this isn’t a movie for subtleties (the leader of the woman cult is named Fima, for god’s sake). If the men seemed less like gross sexist monsters, one could conceivably see the film as homophobic, portraying lesbians as predatory cultists who will drug women to take advantage of them. But by drawing both sides villainously, the film sets Kim up between a rock and a hard place. It isn’t the idea of queerness that makes her ultimately reject the cult’s indoctrination, but the idea of being forced into any choice. The film suggests Kim is bisexual and puts her in a position where the world wants her to decide, leading to a conflict of identity.

Conflicting ideas of sex pop up twice in the film; once in the beginning while Hank and Kim have sex, and again towards the end when Kim is in her deepest sense of madness. A TV turns to a sex scene in both instances, in the first a straight one, and Kim watches it out of the corner of her eye as the couple onscreen appear to be moving in the same pattern as Hank and her. She wonders if that’s all this is, just going through the motion of heterosexuality. When this happens again later in the film, it’s a lesbian sex scene that gets interrupted by Fima’s face, beckoning Kim. Both scenes use media representation of sexuality to show Kim’s journey. She feels almost trapped by the straight sex scenes, and while the lesbian one scares her, it intrigues as well. However, neither is an accurate depiction of sexuality—hers or anyone’s—leaving her still alienated even as she begins to discover her queerness.

The bug cult, ultimately, wants more from Kim than she is willing to give. The three women drug Kim and perform what is suggested to be a sort of cleansing ritual from men, forcing her to have sex with Ricky—the cult’s servant—as one last act of heterosexuality. The rape scene is horrifying, shot with a glowing red light that highlights Kim’s torment, but what comes after is perhaps worse. Kim is left to process and she begins literally twisting herself in knots, first her fingers, then her legs, until she breaks and begins to leak a thick white slime out of her vagina. She is losing her ability to know herself, to have her body as her own. This bit of removal of autonomy is Kim’s last straw, and she tries to flee from the cult, first in the arms of her boyfriend and then to the police once he is killed. Everyone is convinced she is just losing her mind, however. She can’t find any evidence of Hank’s murder for the police, the rest of their coworkers believe him to be gone on assignment, and it appears Kim has no friends outside of work. Even her closest ally, a secretary at the paper, is revealed to be the fourth member of Fima’s bug cult. The film suggests a dichotomy of all men as sexist assholes and all women as bug cult lesbians.

As her final act of membership, Kim is required to bring a male sacrifice for the cult, and Fima has decided it should be Hank’s little brother. Even as Kim attempts to escape from these women, she cannot: they appear on television, talking to her psychically, and eventually in her apartment physically. They force her to go with Ricky to get Hank’s brother and bring him up onto the roof for the sacrifice, killing Hank’s parents in the turmoil. There, Kim commits herself to rejecting the queer fetish lifestyle Fima wants her to adopt, telling her “You never cared about me! You never cared about your daughter! You only care about yourself!” and stabbing her in the chest. Of course, the kinky lesbian cult leader doesn’t mind a little knifeplay, and attempts to finish the ritual without Kim’s help. It’s only Kim’s rejection of her love that destroys Fima’s power; like most cult leaders, she is only as powerful as her followers believe her to be. Without a new source of queer love, Fima’s powers flicker at a crucial moment in the ceremony, and she bursts into flame and falls off the side of the building, mirroring the death that started the process. The film ends suddenly here, with Kim holding Hank’s brother comfortingly, and saying “it’s all over now”.

But is it? Fima’s death being identical to the one at the start of the film suggests to me this is a cycle that remains unbroken. Sure, one of the cult members, even the leader, is dead, but there’s still the other three women. My favorite horror movie endings are the ones that don’t just suggest that evil is still out there, but that this was just a failed cycle in a never-ending game of torture for one trapped soul. Films like THE AMUSEMENT PARK, THE SLAYER, and DEVIL STORY are three that play off an ending that suggests the events of the film may be about to start again, and while INITIATION doesn’t hit the same note as obviously, the sudden ending and repeated death do have some of that same creepiness. It also helps that the fifth and final sequel in this franchise (a loose remake entitled simply SILENT NIGHT was released in 2012), THE TOY MAKER, features two characters from this film in small cameo roles: Kim, and, more interestingly, Ricky. Ricky dies in INITIATION, suggesting one of two things: TOY MAKER is a prequel—the less interesting option and one not really suggested by the film—or the bug cult lives on and has resurrected Ricky for their own twisted purposes. TOY MAKER is also the only other film in the franchise with Yuzna’s involvement (he receives a writing credit) making this connection a little less far-fetched.

SILENT NIGHT, DEADLY NIGHT 4: INITIATION is incredibly unique amongst not only the other films in its series, but the whole Yuletide horror subgenre. It’s a rare one for queer subtext, for whatever reason, and for its full-tilt intersection with body horror. But I think what is most compelling about it as Christmas horror is the fact that it focuses on a Jewish lead, albeit a non-religious one. I can’t think of another Christmas horror flick that has a lead that doesn’t celebrate Christmas religiously, even if they’ve lapsed, which feels like missed opportunities. It’s a natural fit for the lead character who’s having a bad time around Christmas to belong to a religion that doesn’t celebrate it, exasperating the anxieties one feels around a holiday season that doesn’t include them. Instead, most Christmas horror looks at the terror of a holiday that means something happy to the characters being twisted into something dark. Why not take something dark and twist it a little further?

Tags: Brian Yuzna, Clint Howard, Maud Adams, Neith Hunter, Screamquels, Sequels, Silent Night Deadly Night, Silent Night Deadly Night 4: Initiation, Tommy Hinkley

No Comments