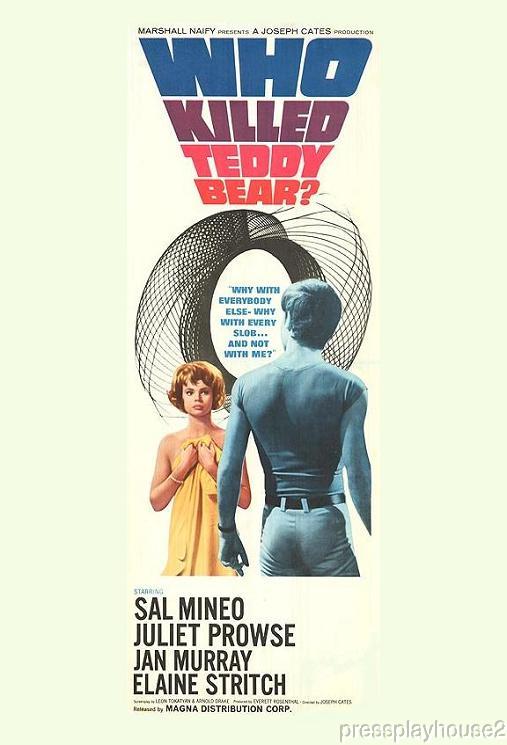

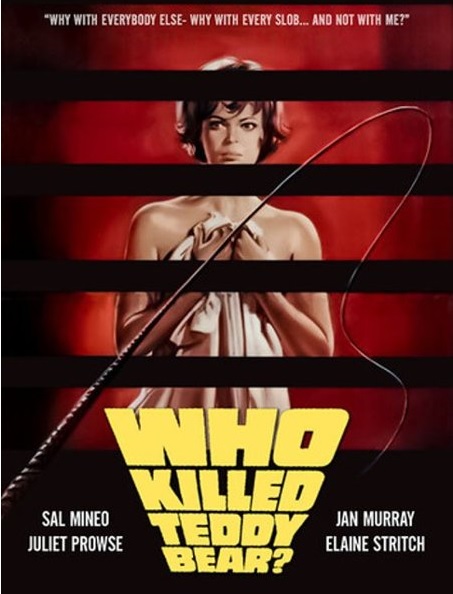

Recently, an acquaintance of mine posted a thread to Facebook about “lost classics.” The term, he felt, was quickly losing meaning. Amidst the current boom of interest in grindhouse cinema and straight-to-VHS-horror, the term “forgotten” had become synonymous with “quality,” to the point every film released between 1960 and 1990 that has since slipped into obscurity was being honored with the status of “lost classic.” I can’t help but agree somewhat, albeit with a caveat. I certainly think those films should be restored, archived, studied, and remembered. They were the product of a unique time in film history, horror and otherwise, and they say quite a bit about the people who made them and the culture that consumed them. However, preserving a film isn’t the same as endorsing it. Not every low-budget slasher or shot-on-video flick deserves the venerable title of “lost classic.” That detracts from the films truly worthy of that designation. Films like WHO KILLED TEDDY BEAR.

Note the absence of a question mark — the film’s title doesn’t have one, either, and that’s just the first (and smallest) of the many oddities that coalesce to make up one of the sleaziest yet well-made grindhouse films ever, a picture that is a “lost classic” in every sense of the word.

Norah (Juliet Prowse) is a small-town girl who’s come to New York to pursue her dream of being a professional dancer. She works nights spinning records at a seedy disco, where she’s watched over by the acerbic-yet-maternal owner, Marian (stage legend Elaine Stritch) and her mute bouncer, Carlo (Daniel J. Travanti). Although the pair may be able to shield Norah from lecherous drunks, lately, they’ve proven ineffective at protecting her from a much more nebulous threat. Norah’s become the recipient of a series of progressively disturbing phone calls, which have escalated from heavy breathing to weird threats to eerily detached descriptions of what she’s wearing and doing inside her apartment. When Norah must give a witness statement to the police after Carlo stabs a guy making improper advances, Marian tries to convince her to tack on an additional complaint about the caller. This piques the interest of Lt. Madden (Borscht belt comic Jan Murray in a rare dramatic turn), a creepy cop who lost his marbles after his wife was murdered and raped (in that order) and is now determined to take down every sex criminal in New York. To that end, Madden has become a deviant in everything but action, turning the apartment he shares with his prepubescent daughter into a shrine to perversion, festooning every surface with pornography, treatises on sex crimes, and, most disturbingly, the audiotaped statements of rape survivors, which he listens to before going to bed at night. Madden becomes obsessed not just with Norah’s case but Norah, and before long he’s convinced her to move in with him and form an ersatz family while he tracks down the creeper.

Abruptly, the film jumps perspective, and we’re introduced to the caller: Lawrence “Larry” Sherman (Sal Mineo), a quiet, polite waiter at the club where Norah works. If Madden were gearing up to be the poster child for maladjustment, Larry’s the brand ambassador: After their parents died, Larry and his sister Edie (played as an adult by Margot Bennett) went into the system, where one of their foster mothers began having sex with the teenaged Larry. A nine-year-old Edie caught them in the act, and in her revulsion and terror, she fell down the stairs. The tumble not only destroyed her beloved antique teddy bear but gave her permanent brain damage. The incident proved similarly traumatic for Larry, and the combination of guilt, sexual abuse, and other unresolved issues have stewed for years to turn him into the self-loathing sicko he is today. Though Larry attempts to sublimate his urges — from marathon weightlifting sessions to indulging in seedy movies at Times Square grindhouses — several incidental run-ins with Norah push him closer to the breaking point, and the running time of the movie becomes a mordant countdown to tragedy.

WHO KILLED TEDDY BEAR is a movie that would court controversy even today; the fact that it was made at all in the 1960s is both a miracle and goes a long way towards explaining its subsequent obscure status. The opening scene features Mineo (wearing nothing but tighty-whities) feeling himself up while making an obscene phone call. From there, it’s a slow descent into the darkest corners of the human soul, as the audience is subjected to frank discussions of sex crimes; the graphic strangulation of a woman with her own stockings; sexual assaults of virtually every permutation (in order: female-on-male, female-on-female, male-on-female); an unsettling treatise by a pair of unrepentant pedophiles on their condition; and, most chillingly, the image of Lt. Madden’s daughter lying awake in bed at night as her father listens to audio recordings of the last statements of women later murdered by their stalkers. It’s a startlingly mature look at the cesspool Times Square was turning into at the time, and it’s a credit to director Joseph Cates and writers Arnold Drake (co-creator of Doom Patrol and the original Guardians Of The Galaxy) and Leon Tokatyan that they wanted to address topics which weren’t being acknowledged in popular culture. While the similarly star-studded POOR PRETTY EDDIE– another spiritually sleazy yet curiously well-cast exploitation flick — leaves the audience scratching their heads, wondering what attracted such talent to something so lurid, it’s easy to see why WHO KILLED TEDDY BEAR looked appealing to its’ cast on paper — socially conscious dramas are the stuff that Academy Awards are made of, and even when the movie is meditating on its’ seedier elements, it’s doing so in a thoughtful way. (Speaking of EDDIE, Leslie Uggams recorded WHO KILLED TEDDY BEAR’s loopy James Bond-y theme song, which was released by Atlantic as a 45). Coupled with that frankness is a nuanced — and bleak — twist on sexual coming of age. Predating Todd Solondz’s HAPPINESS by over thirty years, WHO KILLED TEDDY BEAR equates sexual maturity with the death of not just innocence but goodness. The crimes we behold aren’t committed because men are evil, as films with a simpler outlook might suggest (Marian herself turns out to be almost as dangerous as Larry, and definitely just as predatory), but because sex itself is a negative force. If anyone or anything can be held accountable for the titular crime, WHO KILLED TEDDY BEAR suggests, it’s puberty.

The film isn’t without its faults, though, and along with its’ subject matter, they go a long way towards explaining why the film failed to take off. Cates seems compelled to break the tension he’s so expertly crafted at incredibly inopportune moments, such as the use of an awkward Gilligan Cut after a discussion on stalkers. The too-regular lapses into broad humor and interjections of LAST HOUSE ON THE LEFT-style cornball music are jarring, to the point that some audience members may come away thinking this was meant to be a dark comedy. Then there are a series of drawn-out, meditative sequences in which the camera silently lingers on dancers at a disco, Larry working out, and Norah in a swimming pool. The former seems to be an awkwardly dated way of setting the tone for the movie, as the camera focuses on the preponderance of (gasp) interracial couples at the club. The latter two are both weirdly and uncomfortably erotic, as the camera focuses on Mineo’s sweaty, bulging muscles as he pumps iron… and pumps iron… and pumps iron… and Prowse shows off what years of dancing have done for her legs as she swims… swims… swims. The apparent idea is to put the audience in Larry’s frame of mind by encouraging them to engage in the same sort of frustrated voyeurism, but the effect is more boring than contemplative or sexy. (Tellingly, subsequent versions of the film — in its rare television screenings and arthouse revivals — edit these sequences to varying degrees, to the point that seeing them intact is worth the slog).

Quality aside, WHO KILLED TEDDY BEAR is fascinating as an historical document. The movie was shot on location in Times Square, during a period in which the grindhouses had just established their dominance and the character which would define Manhattan in the dark-and-nasty ’70s was beginning to take shape. From beautiful shots of vintage grindhouses to walking tours of the Deuce, WHO KILLED TEDDY BEAR is a rare glimpse at the environment that birthed exploitation cinema in its’ heyday, and for that alone it’s worth a look.

Unfortunately, that look may be difficult to take. As of 2021, it’s only ever received one official release in the form of a 2009 DVD in the UK (where, ironically, it was rejected by the censors). All other versions floating around are of dubious quality and legality, making WHO KILLED TEDDY BEAR perhaps one of the rarest high-profile films ever made, in addition to one of the best. Hopefully, as more films are resurrected from the purgatory of obscurity, WHO KILLED TEDDY BEAR can finally transcend the label of lost classic and achieve its rightful place as simply a classic.

Tags: Arnold Drake, Bruce Glover, Charles Calello, Crime, Daniel J. Travanti, Elaine Stritch, Jan Murray, Joseph Brun, Joseph Cates, juliet prowse, Leon Tokatyan, Manhattan, Margot Bennett, Neo-Noir, New York City, Sal Mineo, The 1960s, Thriller, Times Square, Tom Aldredge

No Comments