Though scarecrows are infamous Halloween iconography, they’ve been only moderately used throughout horror cinema. A shame, really; that image of empty black eyes and ends of straw poking out of flannel sleeves is effortlessly creepy and makes for a good on-screen monster. Unfortunately, most of the scarecrow’s voyages into celluloid have resulted in very few titles worthy of the potential. 1988’s SCARECROWS is an unusual and quirky slasher/action mashup seemingly inspired by the likes of PREDATOR; 1990’s NIGHT OF THE SCARECROW is an occasionally icky low-budget thriller featuring a very young and beardless John Hawkes; 2011’s HUSK is a decent time-waster with a somewhat mindless concept; and the less said about the direct-to-video SCARECROW SLAYER series, the better. Standing burlap-head and straw-filled shoulders above all that have come before and since is the terrific DARK NIGHT OF THE SCARECROW, a made-for-TV thriller that debuted on CBS on October 24, 1981. Until its resurrection in 2010 for a DVD and Blu-ray release, it had been unavailable for decades outside of used VHS rental copies (which still sell on eBay for $300), living on through bootleg networks and convention copies following its initial television debut. It was a movie very fondly remembered by those who had seen it, but which was at risk of being lost with time—and that would’ve been a crime considering how wonderful an addition it is to both the spooky season and the genre in general.

In a nameless mid-western town, a young girl named Marylee Williams (Tonya Crowe) and a simple-minded man named Bubba Ritter (Larry Drake) play together in the middle of a field. These two are good friends and this really bothers a few people in town, namely Otis (Charles Durning), Skeeter (Robert F. Lyons), Philby, (Claude Earle Jones), and Harless (Lane Smith). Otis and his cohorts believe Bubba is dangerous—and as such, should not be allowed anywhere near children. “He’s a blight…like stink weed and cutworm that you spray and spray to get rid of, but always keeps coming back,” Otis seethes. “Something’s got to be done…but it has to be permanent.” When the kids harmlessly sneak into a backyard to play with a decorative garden fountain, a dog viciously attacks Marylee, and Bubba manages to save her. She’s brought to the hospital bloodied and unconscious, so Otis naturally assumes the worst. He gathers up his hateful posse and they head out to the Ritter farm to exert some private justice. Bubba’s mother (Jocelyn Brando), having hidden her son within the scarecrow poled in their back field, forbids the men from entering the house. She lies and says Bubba is nowhere on the property, but the men know better. They instead begin their search outside, and through the holes on the scarecrow’s burlap-sack face, Otis sees Bubba’s terrified eyes. The men open fire, killing Bubba with a loathsome number of bullets. Then they find out the truth: Bubba hadn’t been the one who hurt Marylee at all, and in fact had actually saved the girl’s life. Otis places a pitchfork in the dead Bubba’s hand, his mind already piecing together a possible way out of trouble. An eerie wind picks up immediately after…proclaiming a vengeance soon to come.

Otis and his posse are tried for Bubba’s murder (rather quickly), but they claim self-defense, and because District Attorney Sam Willock (Tom Taylor) can’t present witnesses or evidence, the judge grants the men their freedom—at least from the courts. Having just gotten away with murder, the men are feeling pretty good…but then each of them begins seeing the Ritter farm scarecrow planted in the middle of their own fields—the same scarecrow Bubba had hidden within before facing their hail of bullets. The men are then picked off one at a time by an unseen killer in the same order that the scarecrow appears to them, as if someone were taunting them…or letting them know who was next.

There are plenty of red herrings to muddy the identity of the killer: maybe it’s Bubba’s mother, who’s lost her mind in a fit of rage and begins tracking down her son’s assassins; perhaps it’s District Attorney Sam Willock, who believes the men escaped justice following his failure to prosecute them; it could be Marylee, out to avenge the death of her friend; it could even be one of the men responsible for Bubba’s death, buckling under the simmering guilt he has successfully hidden away from his friends.

Or perhaps it’s the ghost of Bubba himself, back from the grave to take his revenge. With his own name on that list, Otis’s time is running out, so he sets out to discover the identity of the men’s assailant, leading him into several confrontations with the town’s suspects, including Bubba’s mother:

A friend of mine was killed the other night.

So I heard.

They all think it was an accident. I don’t.

There’s other justice in this world.

Besides the law?

It’s a fact. What you sow, so shall you reap.

DARK NIGHT OF THE SCARECROW is intelligently engineered in its approach, falling back on the subtle and unseen threat shadowing the vigilantes in the darkness and relying on similarly unseen, non-violent means in which those men are dispatched. Of course, one could easily dismiss this as a mandate dictated by the limits of network television standards, but that doesn’t explain away Bubba’s own violent and upsetting death, which occurs in the film’s first fifteen minutes. No, the ambiguity of the force stalking the vigilantes was a purposeful choice by director Frank De Felitta (THE ENTITY), who understands that to show the monster is to take away its power—and ruin the fun. Though DARK NIGHT OF THE SCARECROW is easily classifiable as a horror film, its approach is less about presenting horrific images and more about using classic horror imagery to punish the vigilantes for their misdeeds…which it does. The vigilantes suffer for pretty much the entire film, and they deserve to—not just because of what they’ve done, but because of the remorse they never show for it; they never break down in sobs, never throw themselves at the dead man’s mother’s feet and beg her forgiveness, even if it’s fear that drives them to do it. Without that, DARK NIGHT OF THE SCARECROW becomes a classic morality tale, and because of this, we watch without conflict or guilt as each of the men are psychologically taunted and killed in ways that the hazards of farm life can explain away. The audience never pities them as they’re each killed on their own farms in the middle of the night. We certainly don’t pity Otis, as the film bravely dedicates much of its time with this man who is seemingly willing to do anything to save his own skin…and is very willing to kill again to do so. It’s a bold move to have your audience spend the majority of the film following around a completely despicable character and witnessing his increasingly deadly attempts to escape the consequences badly owed to him. After all, we’re never going to pity him, or show him our sympathies—there will be no catharsis for him—so in the interim until his inevitable fate, we enjoy watching him squirm. His death, for us, will be a release—especially when young Marylee finds herself in peril once more.

There’s no reason at this point to reaffirm Charles Durning as one of the greats (RIP, sir), but I’ll reaffirm, gladly. At this time in his career, Durning was enjoying himself in little thrillers like this, as well as WHEN A STRANGER CALLS and THE FINAL COUNTDOWN, and he was certainly open to taking on the role of Otis, a complete scuzzball in every sense of the word. He’s an unapologetic murderer, this we know, and an insensitive asshole who doesn’t know when to quit as he takes it upon himself to begin harassing Bubba’s mourning mother, whom he assumes is behind the tragedies befalling his fellow vigilantes. But he’s also something else, too. Though the film does a good job of straddling this fine line, it’s very carefully intimated that Otis is a child predator. He’s a single male, one among many in the boardinghouse where he lives, and an earlier scene with Otis and Mrs. Ritter confirms as much, as she tells him she knows “exactly what [he is]. This is a small town. Everybody talks.” This was a ballsy move to impart on this otherwise straightforward, made-for-television movie. It also adds a very seedy new layer: perhaps Otis hadn’t so impulsively killed Bubba simply because the man-child’s friendship with Marylee disgusted him. No, perhaps Otis had been jealous; he may have even been…marking his territory.

Gross.

Larry Drake’s screen time as Bubba is understandably limited, as he’s shot full during the first act, but it’s nice to see him play a simple and innocent character like Bubba Ritter. He is ingrained in our minds thanks to his villainous turns in DR. GIGGLES or the DARKMAN films; typically, our only affiliation we have with the man is being a cigar-cutting or pun-hurling sociopath. To Drake’s credit, it’s always tough to play a character with developmental deficiencies, but Bubba really just comes across as a child—easily prone to fear and shy around girls. He’s charming and even cute—by design, I’m sure, as the filmmakers wanted you to feel especially angry toward the men who eventually take his life.

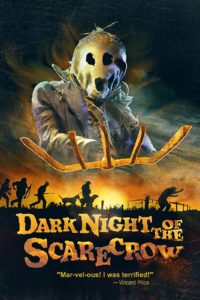

The film is very dissimilar from the previously mentioned SCARECROWS, NIGHT OF THE SCARECROW, and HUSK—those films’ directors were not afraid to make their straw-headed killers vicious and violent. People are hacked apart, strangled, even raped with penetrating straw spears. But in DARK NIGHT OF THE SCARECROW, all the gruesomeness is left to your imagination. The men are killed, oh yes, and in imaginatively painful ways, but never on screen. It’s old school in its execution because it is old school. A swinging shaded bulb complementing a man’s desperate screams is far more affecting than a man being folded in half by random farm equipment front-and-center on screen. It might be a cliché to say that hinging your movie’s horror on its own audience’s imagination is more successful than showing them the blood and guts, but that doesn’t make it any less true. Vincent Price himself has a pull quote on the current video release, calling the movie “marvelous” and claiming he was “terrified,” and while most fans would look to this as a solid endorsement, being that Price was and is horror royalty, it’s also indicative of what kind of experience the movie is going to offer—the same kind offered by Price’s own films during the classical era of less-is-more filmmaking.

Despite the obvious constraints of a television budget, director De Felitta shows real skill and creativity. The first scene of the ghostly Ritter farm scarecrow stuck into Harless’s field is captured in one extreme long shot, making the scarecrow barely visible, yet still unnerving and nightmarish. The second sighting in Philby’s field is even better; we see the man looking horrified at something off-screen in the faraway distance, and he begins to run toward it. Finally, he falls to his knees as the camera pulls back…and reveals the scarecrow.

Stationary bird-scarers have never been creepier.

De Felitta also knows how to use the quiet mid-western night to maximum effect. What should be peace and solitude is instead interrupted by the humming of machinery kicking on by itself, or the squealing of farm animals disturbed by something that doesn’t belong, or the crunching sound of methodical footsteps. It’s classy and familiar, yet also entirely effective. But what is the thing hunting down these vigilantes one at a time? Is it a mortal man or woman bent on revenge, or Bubba’s ghost back from the grave? Strangely, the cut of the film that aired on television is very slightly different from the one released on home video…and not because of any violent content that had to be removed from the broadcast. No, instead, while the broadcast version keeps the identity of the vengeful force ambiguous to the end, the video version shows its hand with one single shot, firmly identifying the previously unseen killer—which may be enough to rankle first-time viewers depending on their preference. (I prefer the video edit.)

DARK NIGHT OF THE SCARECROW was specifically produced to air the week leading up to Halloween, with a second-act sequence even taking place during a Halloween dance at the local school. Though shot in California, its anonymous landscape offers that rural, any-town America vibe where the heart of Halloween seems to live—the kind of place rife with sprawling farms that turn into haunted hayrides for one month out of the year, and which have fields bursting at the seams with corn stalks and pumpkins. Between its scarecrow theme and concept of ghostly (or is it?) vengeance, and with the added benefit of seeing the conflict play out across Halloween dances and those aforementioned pumpkin-strewn fields, DARK NIGHT OF THE SCARECROW is essential Halloween-night viewing. Out of all the seasonally themed titles I watch every year (and there are a lot), this one in particular is always the one I use to say farewell to another October season. It’s been an annual Halloween night tradition for the last ten years and I expect that to continue long into the spooky future.

Tags: Anniversaries, Charles Durning, Claude Earl Jones, Dark Night Of The Scarecrow, Frank De Felitta, Jocelyn Brando, Lane Smith, Larry Drake, Robert F. Lyons, scarecrow, Tom Taylor, Tonya Crowe

No Comments