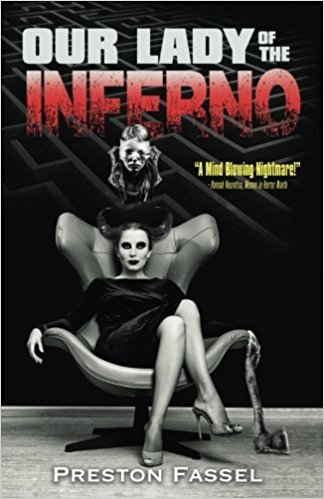

I say this as a positive: it is very clear that a first-time novelist wrote Our Lady of the Inferno. There is an overabundance of detail given to the early ’80s locations, music, movies, and fashions of the time, as though every last detail discovered through extensive research was used. The dialogue is incredibly specific to each character to the point where it is never in doubt who is speaking even if their style of speech is sometimes awkward to read. The subtext of female empowerment in a world where the female characters are seen less as people and more as items to be bought and sold is so dominant that it repeatedly rises to the surface and threatens to overwhelm the down-and-dirty exploitation story that is used as the hook.

I say all these things as positives because—even though Fassel occasionally allows the forward momentum to get bogged down in long descriptive passages or burrowing deep into the internal thoughts of his characters—they show ambition to tell something deeper and smarter than just another 42nd street descent into sleaze for the sake of sleaze. I will take protracted dialogue and descriptive sequences if they add to the characters and deepen their bonds/divides. Some authors fail to do this and the results are self-indulgent. Fassel thankfully never becomes self-indulgent; he may overreach at times, but always in service of fleshing out his characters.

In a reversal of the usual with genre fiction, the protagonist is more interesting than the villain of the piece.

The year is 1983 and while Ginny Kurva is excited about the impending launch of the space shuttle that will take Sally Ride into space, she has more grounded concerns on which to focus. First on Ginny’s list of priorities is taking care of her paraplegic younger sister Trish. Even though she is only a few years older, Ginny acts as mother, sister, and teacher to the girl. After Trish, Ginny has to worry about recruiting, training, and trying to instill some sort of education to the group of prostitutes who work under her. Part of her duties is to not only make sure they are doing their jobs, but to also protect them from the most unsavory of potential predators on 42nd street and also from her boss, an enigmatic and dangerous pimp and drug dealer who calls himself Colonel Banizewski. Coming in a distant third for Ginny is taking care of herself—a battle she is losing between a descent into alcoholism and pushing away any potential friendships from the women who work for her and Roger, a comic book store employee who she enjoys mocking exploitation films with her at the local grindhouse.

The flip side of Ginny’s desperate fight for daily survival is Nicolette Aster. Nicolette maintains a successful career as an administrator at the Staten Island landfill and is prim and proper in her behavior in a Stepford Wives kind of way. But Nicolette has more than a few screws loose. While she maintains appearances for her co-workers, she spends her off hours submerging herself in a fantasy world where she is a mighty Minotaur and has made her own labyrinth in the sprawling mess of the landfill. The problem with being a Minotaur in a labyrinth is the need for victims. This is a problem that Nicolette solves by kidnapping prostitutes from 42nd street, drugging them, and dropping them in her lair, where she hunts them in an elaborate ritual. And as spring gives way to summer, she has her sights set on Ginny as the ultimate prey.

This feels like the set up for a quick, down and dirty exploitation movie full of sex, violence, and plenty of bad taste moments, only in novel form. Fassel does deliver on that promise with certain elements (Ginny just happens to be a Martial Arts badass, the infamous shotgun blast to the head from MANIAC is referenced twice, one of Nicolette’s killings results in dismemberment and bloody decapitation), but he admirably keeps the focus on his characters even when it would have been easier to cut some of the character beats in favor of more plot points of Nicolette’s grisly hunts or Ginny’s interactions with clients.

I do wish Fassel had found a way to get the reader more in touch with Nicolette’s warped view of the world. As a villain, she is frightening, but I get the feeling that the author also wants us to at least pity this seriously damaged and confused character. Unfortunately, she is presented as so out of touch with humanity and so lost in her increasingly demented fantasy world that she never registers as much more than a monster lurking in the background, picking off side characters and plotting her ultimate hunt as she stalks Ginny from afar.

This inability to connect the reader more successfully with Nicolette keeps the final showdown with Ginny from packing quite the punch it should have. But while their battle is a little anticlimactic, it does not take away from the story of Ginny and Trish, which forms the heart of the novel.

Ginny is difficult to classify as a straight hero. For as much as she tries to help the women who work for her, she also constantly manipulates them and preys on their inexperience to keep money rolling in. This ambivalence that Fassel works into how the reader sees Ginny is tempered just enough by having Trish around. Operating as comic relief, Ginny’s conscience, and just generally the only major character who is always a joy to spend time with, Trish is just as important to the reader as Ginny. Making their relationship the focal point of the novel is a wise move by Fassel.

It may be about fifty pages too long and stray a little far from the promise of an over-the-top grindhouse experience in book form, but Our Lady of the Inferno is a very good first novel. Fassel understands the importance of making the reader care about the characters to heighten the tension. He is a horror writer to keep an eye on, going forward.

Our Lady of the Inferno is currently available on Amazon.

No Comments