Julia Ducournau’s TITANE is a difficult film to pitch to people. The plot is quite minimal, but there are twists that are best left unspoiled. The movie contains graphic sex and violence, yet it’s not as dark as those moments would suggest. TITANE is full of gorgeous, singular imagery that is impeccably composed and utterly haunting, but often in service of some unsettling idea. The story is inconsistently detached from reality, but even those nightmarish bits of magical realism and leaps of logic serve to address all too real and human emotions. Ducournau’s sophomore effort isn’t a pleasant film, but it is a rewarding one where mindsets that should be in opposition to each other instead tenuously co-exist to produce a unique experience that has echoes of other works, yet remains its own misfit mutant, born of pain and love.

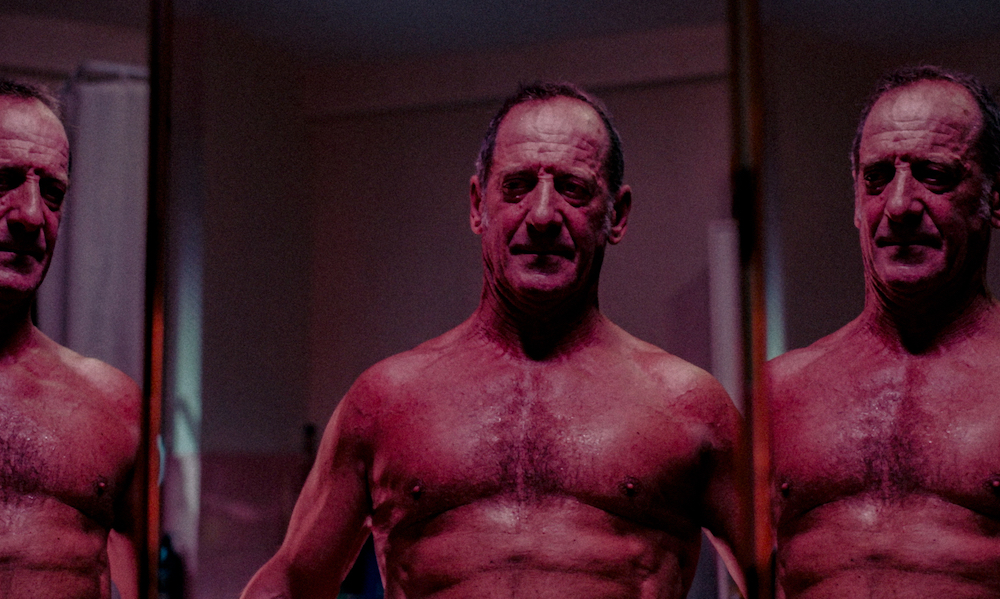

As a young child, Alexia has titanium plates placed in her head following a terrible car accident. While before the crash she displayed obnoxious spiteful behavior, during her recovery the girl (Adèle Guigue) isn’t outwardly angry though a seething hatred seems to burn behind her eyes. She is eventually released from her halo and able to re-enter the world, her first act is to hug the very car in which she was injured. Later, as an adult (played by Agathe Rousselle), Alexei is a dancer who hypnotically writhes atop cars at events to mesmerized onlookers and legions of fans. She still lives with her parents (Bertrand Bonello and Myriem Akheddiou), but they seem to be in a constant uneasy cold war set to boil over. She tries to connect with fellow dancer Justine (Garance Marillier), but Alexia appears unable to properly regulate her emotions with others, finding greater companionship with the cars on which she dances. Oh, and she also has a penchant for killing people by stabbing them in the brain. Eventually Alexia ends up crossing paths with Vincent Legrand (Vincent Lindon), a fire captain whose refusal to believe his son died many years ago has destroyed his marriage, pushes him to be a hardass with the other firefighters, and drives him to use steroids to keep up physically with the much younger men. A combustible pairing, both Vincent and Alexia undergo profound mental, emotional, and physical changes as their scars collide.

The most obvious point of reference for TITANE is David Cronenberg. There are many elements of “body-horror” in Ducournau’s film — including surgical scenes reminiscent of DEAD RINGERS, the biomechanical intersections of VIDEODROME and EXISTENZ, and especially a very specific type of relationship with cars not seen outside of the master of horror’s CRASH. But while TITANE’s script (by Ducournau with collaboration from Jacques Akchoti, Jean-Christophe Bouzy, and Simonetta Greggio) and visual motifs share strands of DNA from the elder Cronenberg’s work, it is a completely different emotional approach. Many body horror movies tend to look at the flesh as a traitor that people can’t escape; whether it’s due to disease or aging, biology will ultimately fail us. This often results in cruel or cold characters who try to be detached from their cellular structures. Maybe they idolize automobiles or find ways of transmuting mechanical processes into some organic hybrid. There is a revulsion in most body horror films, finding the physical form limited and prone to agonizing entropy.

TITANE has parts of that, with Alexia having a sociopathic detachment from her parents and some of her victims. Her most emotive moments in the first half of the film are based solely around cars. Rousselle’s lithe body emerging from a tense status of fight or flight to engage with these machines. But there is feeling beneath that cold exterior, which becomes ironic as a plot development introduces something else physically beneath Alexia’s exterior. The biological fascination falls away to examine the more ethereal and psychological bonds that connect people. There are still dance sequences and other wordless scenes where the gyrations and physicality of people are observed, and certainly the bodies’ transformations remains a major theme throughout TITANE; but it becomes entangled with the deeper emotional aspects of these changes in ways that are heartwarming and horrific in equal measure.

For her first feature film, let alone her first lead in a movie, Rousselle does a tremendous job. She is bratty, stoic, terrifying, hilarious, and intoxicating in equal measures as Ducournau calls for her character to be in each scene. It never feels like a forced performance or a patchwork of moments, but a cohesive person with all manner of scar tissue that causes problems she can possibly recognize but certainly can’t change. The physicality, not just in the dance routines but also as she must adopt various personas around various people, is a truly impressive display of talent.

Unbeknownst to this ugly American, Lindon is a major star in France — basically akin to De Niro in the states. His choice to appear in TITANE, and his trust in Ducournau’s process, is admirable and pays off with an outstanding performance that also combines many emotions into one slowly expanding explosion. He is bursting with rage, petrified of aging and diminishing, and hilariously bizarre; he manages to be an open wound that one wishes to help but dare not approach for fear of attack. Lindon infuses Vincent with a dangerous enigmatic streak where audiences aren’t sure what he knows or what he’s planning. Is this someone to be afraid of or someone to fear for? The answer is “yes.” Such layered acting is mesmerizing, and watching the veteran movie star work with the inexperienced film actress with these constantly morphing characters is astounding.

TITANE is a gorgeous film, with director of photography Ruben Impens using beautiful sweeping shots of scenes that combine with the production designs of Laurie Colson and Lise Péault to create rich visuals that are vibrant in one moment, and then sterile in the next. Little details and uses of color allow for such inhumanity and lushness to pop in the frames, which is also bolstered by similar touches by costumer Camille Champenois and set decorators Axelle Le Dauphin, Emmanuelle Olle, and Bruno Taddei. TITANE finds beautiful ways to show the ugliness in humanity, and the inevitable bonds formed between souls.

Much like her first movie, 2016’s RAW, Ducournau has created a beautiful and unique work that has elements of previous filmmakers but is ultimately singular. Also like RAW, it’s unlikely that people will revisit TITANE many times after initial viewing. Certain scenes will be watched multiple times, and images lifted and used in all sorts of compilations or as their own points of references for future directors, but it is not a pleasant experience or an ultimately enjoyable destination. This isn’t a negative, or criticism of TITANE. The film is rewarding and immaculately constructed, but the apparatus it has built is an often unpleasant and uncomfortable one that pushes away as much as it entices. With just two titles, Julia Ducournau has proved herself as a force to be reckoned with in filmmaking (especially in horror). With a wondrous mind that conceives of exquisitely horrific yet deeply touching sequences and stories, Ducournau is a bold visionary able to marry the uncomfortable with the alluring to create lasting films that depict humanity in all its glory and repugnancy.

Tags: Adèle Guigue, Agathe Rousselle, Alamo Drafthouse, Axelle Le Dauphin, Bertrand Bonello, Bruno Taddei, Camille Champenois, Canal+, Ciné+, David Cronenberg, Emmanuelle Olle, Fantastic Fest, Fantastic Fest 2021, Garance Marillier, Horror, Jacques Akchoti, Jean-Christophe Bouzy, Jim Williams, Julia Ducournau, Lais Salameh, Laurie Colson, Lise Péault, Myriem Akheddiou, neon, Ruben Impens, Séverin Favriau, Simonetta Greggio, The Kills, The Zombies, Vincent Lindon

No Comments