Good vs. evil — at the end of the day, it’s what most stories boil down to. As I write this on the evening of August 12th, 2017, evil has reared its ugly head in this country once again, as three people lay dead thanks to violence perpetrated by a bunch of Nazi assholes who have re-branded themselves as the “alt-right,” but they’re not fooling anybody — evil is evil is evil, no matter what guise it cloaks itself with. Just ask Jack Kirby, who I’m glad didn’t live long enough to see this sorry day — he knew better than most.

Kirby’s experiences on the front lines of WWII drove home lessons he’d already learned about prejudice and anti-Semitism in his youth — let it go unchecked, and people are gonna get killed — and he knew exactly how to confront it, both in representation and actuality: When his famous image of Captain America punching out Hitler pissed off Nazi “fifth columnists” here in the US to the extent that a handful of them decided to wait for him outside his office one evening, he rolled up his sleeves, headed out there, and prepared to do the same thing to them that his hero had done to their execrated leader on the printed page. By the time he got to the street, though, these supposed “tough guys” had already cut tail and run like the pathetic cowards they no doubt were. I would argue that in life full of towering, brave, and singular achievements, The King never stood taller than he did that night.

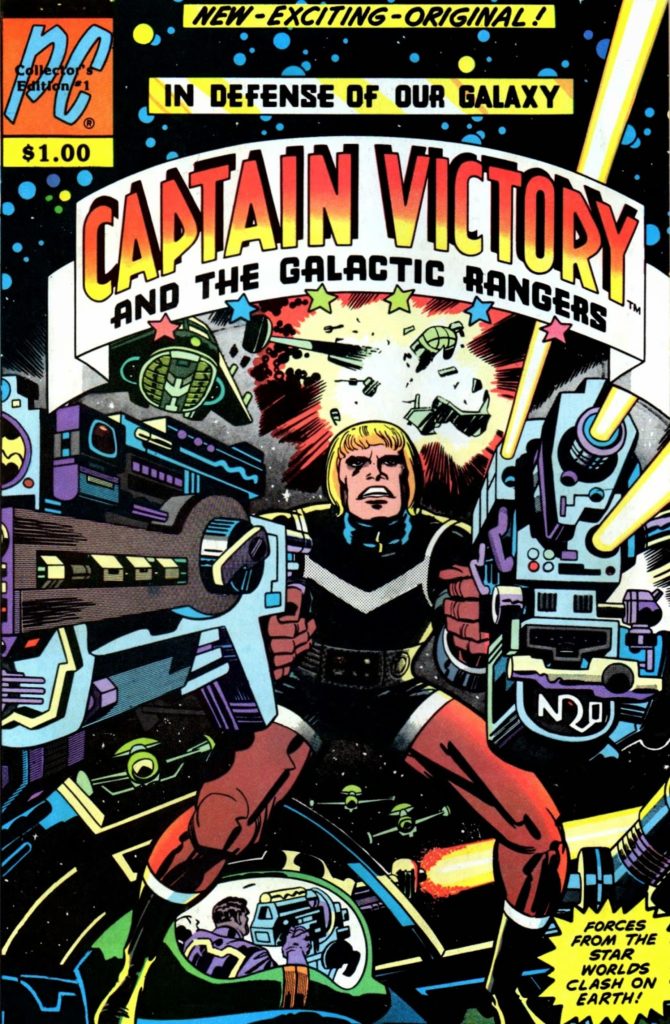

Fast-forward to 1981, and this truly great man had been thoroughly and shamefully used and abused by his corporate bosses, despite the fact that his creations had already earned millions for them and would go on to earn billions. Jack had understandably had enough and, in 1978, took his limitless skill and imagination to the world of animation, where he made more money than he ever had and, for the first time, even had company-provided health insurance for himself and his family. And yet, still the creative fires to invent new heroes, new villains, and new worlds for the four-color funnybooks still burned within him, and so, when a couple of comics retailers and distributors came to him with their idea to start up a publishing company — one that would, crucially, offer full copyright ownership to its creators and distribute their wares exclusively via the direct market (a truly radical concept at the time, as newsstand sales still accounted for the vast majority of comic book purchases) — Kirby was “all in” and became the first creator to sign on with the newly-minted Pacific Comics. And he had just the concept to bring to bring to the table.

According to his former assistant Steve Sherman, the basic framework for what would eventually become Captain Victory And The Galactic Rangers was originally developed by Kirby, with a bit of “sounding board” input from him, as a potential screenplay after the release of, and at least partially in response to, Steven Spielberg’s CLOSE ENCOUNTERS OF THE THIRD KIND, which Jack felt presented an overly-optimistic view of what the first contact between humans and aliens would look like. Why naively assume, Jack reasoned, that the so-called “space brothers” would necessarily be friendly? And what would happen if, in fact, they weren’t?

No Captain Victory film ever came to pass, needless to say (and its mostly-Earthbound story was radically different from what eventually did), but the idea still seemed like a good one to The King, and when the time came to flesh it out more fully, he gave us what would become his last great cosmic epic.

Captain Victory And The Galactic Rangers #1 (cover-dated November 1981) makes its grand ambitions known immediately: “Where this force arrives, a saga begins!!” is as much a statement of intent as it is an introductory shot across the bow, and the action begins immediately and doesn’t let up. How many first issues literally kill off their hero before we’ve even had a chance to get to know them? How many take place almost entirely on spaceships, with no attempt to “ground” things in a recognizably human context until the last couple of pages? How many bowl you over with page after page of magnificent, high-concept technology without giving you a chance to catch your breath? How many start by surveying a planet that’s already been destroyed, letting us know right off the bat that in this story, the good guys don’t always win?

The quick answer to that, of course, is “none.” The equally-quick explanation? Because nobody other than Kirby could pull it off, and they damn well knew it.

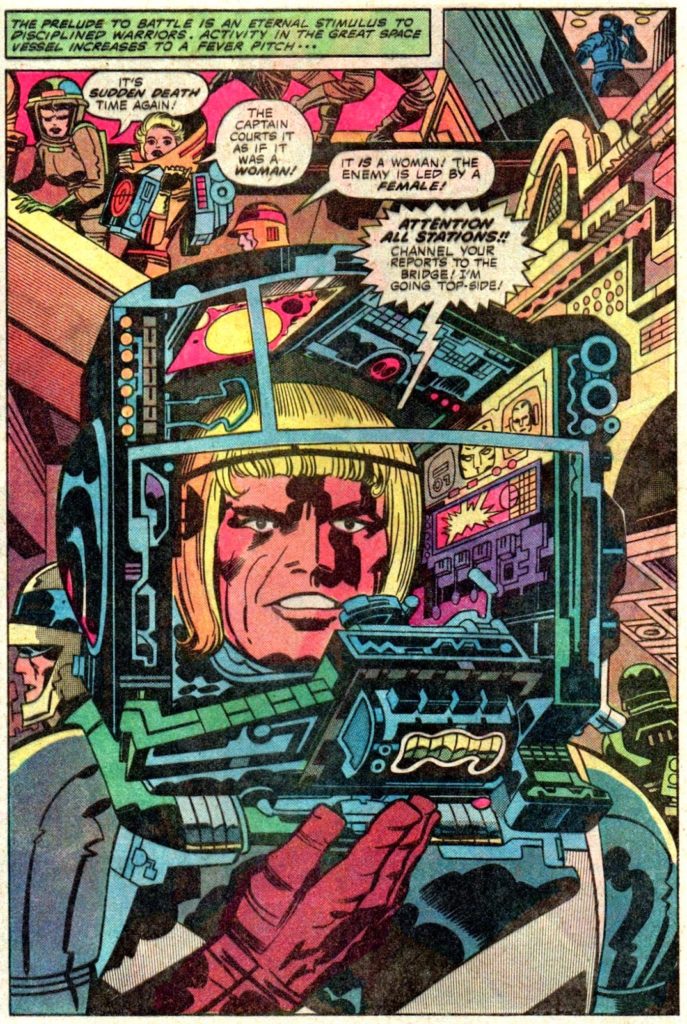

To be sure, if bold, broad strokes aren’t your cup of tea, this comic will alienate you from jump. The King is too busy pouring it all out onto the page to hold your hand, and keeping up with his mile-a-minute imagination is up to the reader. After years of being reined in by tight editorial constraints, Kirby made the most of his newly-found (and hard-earned) creative freedom, and the sheer onrush of dazzling output on display here is exhilarating. One gets the distinct (and accurate) impression of an imagination unchained, unencumbered, and frankly unconcerned with dull and conservative comic book norms. The crew of the incredible Dreadnaught “Tiger” military space-vehicle risks death — shit, total annihilation — with every breath, and with the fearsome Insectons, a foe that literally hollows out and sucks dry entire planets, to defeat, half-measures aren’t even an option.

This non-stop “siege mentality” has created a unique, hard-edged, and frankly hyper-masculine culture within the Ranger ranks, and while Captain Victory himself bears a certain physical resemblance to previous Kirby protagonists such as Thor and Ikarus, he’s shown immediately to be far more mortal than any of them — even if he can’t exactly die, thanks to an endless supply of clones that his consciousness can be, in modern parlance, “uploaded” into. And herein lies one of the fascinating moral conundrums at the heart of this series : the Rangers themselves, while not enslaved to a “hive-mind” like their Insecton adversaries, are every bit as interchangeable and expendable, and even though their ranks are full to bursting with any number of alien races and species, some of whom are quite easy for readers to relate to (Major Klavus) and others decidedly less so (Mr. Mind), true and authentic individuality is effectively subsumed, if not outright obliterated, by their rigorous training and unwavering sense of mission. What, then, are the “good guys” really fighting for here?

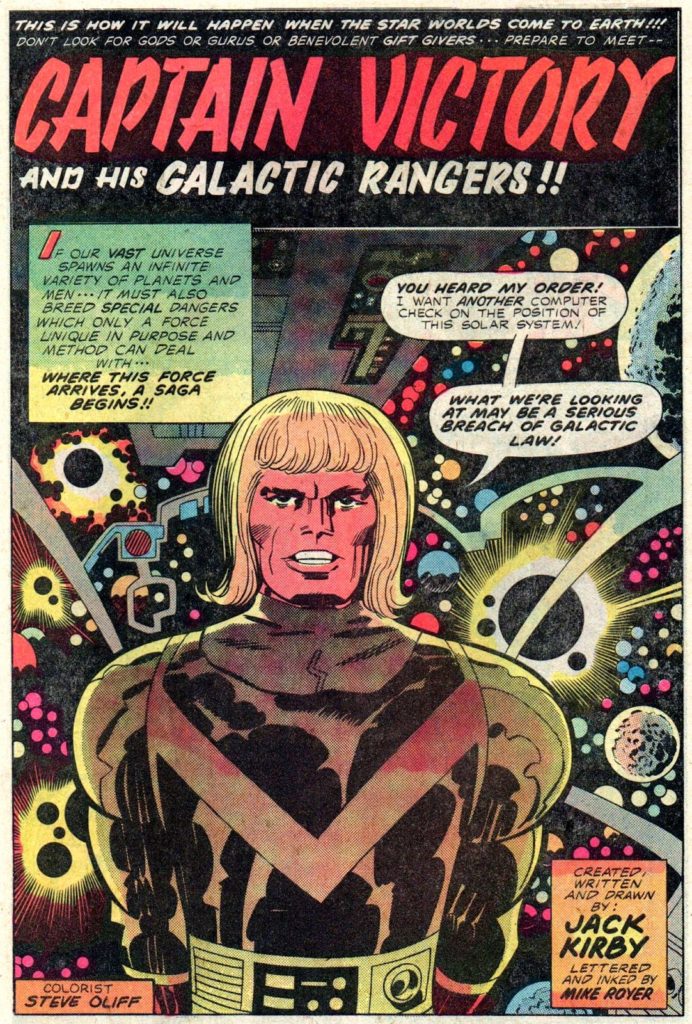

Artistically, Kirby’s never been better than he is this book (and that’s saying something), especially in the first handful of issues, where he is aided and abetted by his finest-ever collaborators, inker Mike Royer, who understood Jack’s interplay of both line and shadow better than anyone else who ever embellished his work, and colorist Steve Oliff, who made flawlessly intelligent and creatively bold choices in every panel on every page during his short tenure on the series. This is a veritable “murderer’s row” of supporting talent, and the result is art that just plain shines. I say without any hyperbole whatsoever that “awesome” is probably too small a word to describe the raw power of the visuals on offer in this comic.

I’d also contend, although received “wisdom” among comics fans has long maintained otherwise, that Captain Victory And The Galactic Rangers #1 marks a monumental leap forward in Kirby’s amazingly singular writing style. Some may trot out tired and dismissive terms such as “clunky” and “tone-deaf” to describe Jack’s latter-period scripting, in particular his dialogue, but I would counter that by calling it “majestic,” “sweeping,” “forceful,” and, most especially, “operatic.” There is a deliberate rhythm and cadence to it that no one else can effectively duplicate — no one should even try — that’s informed by Jack’s extensive reading list (everything from pulp sci-fi to “The Beats”), his love for authentic Shakespearean iambic pentameter, and his first-hand knowledge of military “barracks talk” that coalesces into something altogether brilliant and inimitable.

Like all of The King’s best works, though — and I don’t hesitate for a moment to include this series, and this issue in particular, among those exalted ranks — the philosophical discourse that runs through both writing and art here is where the real “action” is to be found for the considered and analytical observer. Good vs. evil may be at the heart of it, but it’s not the end-all and be-all of this comic — rather, it’s merely the starting point. The extent to which the former, in it attempts to defeat the latter, actually becomes it is the central question that Kirby is asking here, and for all its thematic and conceptual bombast, Captain Victory And The Galactic Rangers #1 isn’t a broadside or even a treatise on the subject, but rather the beginnings of a deep conversation, one which richly rewards the fully engaged reader by providing a conceptual framework through which they can intuit the answer for themselves.

Tags: Comic Books, Comics, Jack Kirby, Mike Royer, Pacific Comics, Steve Oliff

No Comments