Slasher movies are inherently formulaic: depending on your persuasion, that’s either part of the

charm or part of the problem. Most of these films unfold like clockwork, guided by specific cliches and conventions that have become features rather than bugs, and they eventually became so codified that they inspired postmodern subversions, suggesting the only way out of the doldrums is hacking right through them with your tongue planted firmly in-cheek. The most notable of these subversions arrived nearly 30 years ago with SCREAM, a film that skewered “the rules” of the genre to thrilling effect. But far from being the final nail in the genre’s coffin, Wes Craven’s seminal slasher gave it a new lease on life that it’s continued to enjoy in the years since: fittingly, this genre simply refuses to die, no matter how well-worn it may be. But as it lumbers into 2024 — a good 40 years since reaching its cultural zenith — it’s fair to wonder if anyone can revolutionize the genre once again.

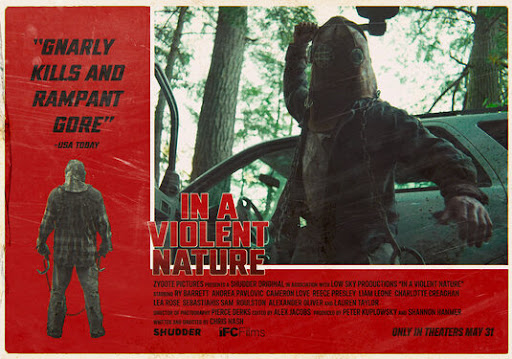

Enter Chris Nash, who rises to the challenge with IN A VIOLENT NATURE, a film that strips the slasher down to its essence as it confronts its conventions and probes just what audiences crave from it. The result is a compelling paradox that’s both rooted in the genre’s formula yet defiant of it all at once: You could easily imagine IN A VIOLENT NATURE being released in 1984, but it also feels like it could only be released now, in a moment where a filmmaker like Nash can toy with the formula and reinvigorate it through sheer force of stylistic will. Simply put, IN A VIOLENT NATURE is a movie you’ve seen a million times before, but it often feels like an alien experience — there’s something just off-kilter enough about its style and sensibilities that it feels like an impossible thing in 2024: a fresh, vital take on a slasher movie.

By now, you may have heard that the film’s stylistic gimmick hinges on Nash’s decision to follow

Johnny, an enigmatic masked maniac who inexplicably rises from his grave in the Ontario woods to wreak havoc on anyone who crosses his path. It’s not exactly couched from his point-of-view, and it’s more accurate to say the camera hovers around him, but the choice starkly frames the film from a unique vantage point. Slasher films have asked audiences to identify with or even idolize maniacs before, but something about this detached, fly-on-the-wall technique almost feels anthropological and truly unlike anything else within the genre. The closest comparison I can muster is the prowling, roving camerawork of THE TEXAS CHAIN SAW MASSACRE, but even that sells it a little short because IN A VIOLENT NATURE is even more detached and removed than Hooper’s film. Nash simply trains his camera on Johnny and follows his horrific exploits like a documentarian, an approach that ultimately highlights exactly what the title suggests: this is just pure, animalistic nature on display.

Eventually, Johnny crosses paths with a group of campers whose campfire tale provides some

context for the carnage. It’s typical slasher movie stuff: one of the kids relays a tale from his uncle

about a tragic accident 70 years ago that portended various massacres over the years, including one within the past decade. Johnny is a damned soul, forced to resurrect anytime someone swipes his mother’s necklace, a backstory that feels awfully derivative of Jason Voorhees, the genre’s ultimate mama’s boy. For all its stylistic bravura, IN A VIOLENT NATURE largely does little to resist the narrative conventions of the slasher genre, creating the uncanny effect of watching a familiar tale unfold in unconventional stylistic fashion as Nash draws the audience into this backwoods mayhem with long takes, unorthodox angles, and an immersive sound design that gives the film a haunting quality.

Few slashers earn that kind of distinction: for the most part, this genre does not seek to genuinely

haunt audiences as it hurries to serve up cheap, gory thrills. But Nash resists this urge by patiently establishing ambiance and atmosphere first. IN A VIOLENT NATURE is almost hypnotic in its early going as it lulls you into its methodical rhythms, emphasizing the “stalk” in the “stalk-and-slash” formula. Instead of generating tension or suspense, these stretches simply create an air of inevitability: these kids might be goofing off around the campfire for the moment, but nature will soon take its course. There’s nothing especially tragic or even scary about it: it’s simply the way things are. By remaining at such a remove from the victims, Nash underscores how disposable characters can often be within the slasher formula — their most important quality is usually their spectacularly gruesome demises.

Of course, the gory payoffs are part of the formula, and IN A VIOLENT NATURE is more than eager to oblige. Johnny is as vicious as any of his slasher predecessors, and he’s armed with a variety of murder implements allowing him to carve an incredible path of destruction. Each kill sequence is impeccably crafted with gnarly, ultra-realistic practical effects that emphasize just how fucking terrible it would be to die in such a manner. One particularly unfortunate yoga practitioner winds up on the very wrong end of one of the most outrageous slasher movie deaths ever brought to the screen. I know that sounds hyperbolic, but I’ve never seen anything like it before, and I’m sure it’s going to be the film’s calling card going forward. It’s not the only memorable bit, either: there’s a long, postmortem dismemberment that reveals Johnny’s twisted curiosity, not to mention two absolutely insane face-splatterings.

However, none of these sequences inspire a twisted sense of shock and awe that often drives the

slasher genre. These kills don’t feel like spectacle or even sheer provocation because they’re

captured in the same calm, clinical manner as the rest of the film. The violence is simply another

matter of fact, a blunt endgame to these horrific proceedings. You don’t sense the raucous fun of

FRIDAY THE 13th, much less the sort of demented glee of the TERRIFIER films — this violence forces you to confront what lies at the heart of this genre and questions the very impulses behind it by stripping it of any sense of emotion.

In an era where the slasher genre has been thoroughly exhumed, dissected, subverted, and

deconstructed, IN A VIOLENT NATURE boldly pulls audiences back through the blood-stained looking glass by stripping it down to its elemental core. It’s not overtly meta (one of its few winks comes in the form of a deep-cut casting choice at the end of the movie), yet you can’t help but gather a sense of self-awareness because it’s like Nash started with the most obvious slasher movie homage set-up imaginable (“What if I just ripped off FRIDAY THE 13th?”) but decided to make every counter-intuitive choice from that point forward. He doesn’t just zig where you might expect him to zag: he almost strays completely from the path altogether, so you have this wicked slasher premise, complete with a hulking, masked maniac that could be the genre’s next icon, only it does exactly the opposite of what audiences expect.

It’s a slasher movie turned inside-out, where most conventional choices are upended. Instead of

even feigning the most obligatory character development for the victims, we spend more time with and learn more about Johnny, to the point where viewers genuinely empathize with this

psychopathic man-child. Instead of generating suspense with obvious musical cues and typical

editing rhythms, it’s an ambient hangout movie that just happens to be following a guy who

bludgeons everything in his wake. And instead of building toward a raucous, intense climax, it ends on a downright anticlimactic note that defies this genre’s formula altogether. A final girl (Andrea Pavlovic) emerges, only to ultimately face a horrific, traumatic void of this inexplicable encounter.

Most slasher movies end with a final jump that insists the terror will never truly be over, but IN A VIOLENT NATURE only suggests this with lingering shots of empty spaces, hinting that true escape will never be possible. Contrary to what many other films in this genre may offer, there is no catharsis to be found in this violence — instead, there is only violence, and it ends just as inexplicably as it begins. It’s also sure to resume at some point, not because evil never dies but because it’s simply in Johnny’s nature to kill and kill again. In a movie full of bold choices, this denouement — which deprives audiences of closure — is the boldest because you’re simply left with your own expectations of bloodlust and forced to reckon with what that means about your own nature.

Tags: Andrea Pavlovic, Canada, Chris Nash, Horror, Slashers

No Comments