When we think of Godzilla, we think of the ocean-dwelling beast (disturbed by men) that came ashore and had the people of Tokyo Bay fleeing in terror. When we think of Cthulhu, the most well-known creation of horror author H.P. Lovecraft, we think of the same thing: a grotesque, gargantuan creature that came from the sea (awakened by men) and caused mayhem thereafter. While they are definitely not the same creature (nor is one the direct inspiration for the other), it’s safe to say that Godzilla’s original 1954 film, Gojira, is heavy on the same elements that one can find in any Lovecraft work.

“It must be remembered that there is no real reason to expect anything in particular from mankind; good and evil are local expedients—or their lack—and not in any sense cosmic truths or laws.” — Lovecraft’s essay, “Nietzscheism and Realism” from “The Rainbow, Vol. 1”

Godzilla is a neutral evil; neither good nor bad. He is not laying waste to the land out of some nefarious desire; rather, he’s simply doing it because that’s what he does. It’s his instinct, his natural order. The seaside villagers of Odo Island regard him in awe as a result, and any reader of Lovecraft will see echoes of the Great Old Gods and the Outer Gods in this awe.

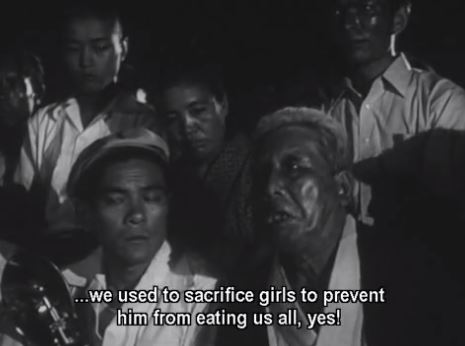

The timeless villains in Lovecraft’s stories such as “The Call of Cthulhu” and “At The Mountains Of Madness” accept and observe a set of universal truths, with no regard for anyone else’s understanding of said truths. The Elder Gods, the Ancient Ones, and the Outer Gods all know a universal order, and act accordingly. Godzilla (and most beasts of kaiju cinema) do the same. Like the villagers of Gojira, humans of Lovecraft’s stories often interpret these rules and universal truths as magical, cosmic. Early in the film a village elder admits that the islanders had committed human sacrifices to Godzilla in the past, in order to placate the monster’s anger. Their lack of understanding of this unfathomable creature was replaced by a religious reverence. Not that it mattered to Godzilla; he was going to do what he has always done, anyway —— annihilate. The humans’ feelings about the matter made no difference to him.

Morality, in Godzilla’s eyes, was an unsubstantial humanistic concept. Like the Lovecraftian beasts of old, Godzilla was largely indifferent to the plight of humanity. The citizens of Odo were helpless to watch the creature wreak havoc, and could only take cover and wait for the nightmare to end. This all ties back into a running theme in Lovecraft’s dark fiction: human hopelessness.

Watching Godzilla Hulk-smashing buildings and tossing cable cars like Frisbees calls attention to the utter triviality of our existence. All of our time and energy spent to erect great structures and pat ourselves on the back for how advanced we are is rendered moot in the face of an ancient beast that can smite us without a second thought, as the boot does to the ant. Lovecraft had a name for this depressing revelation: cosmic indifference. It put the human race on par with insects and plant life, which was and still is terrifying. The horror is in our relative insignificance, no matter how far we’ve come.

“We live on a placid island of ignorance in the midst of black seas of infinity, and it was not meant that we should voyage far.” — The Call of Cthulhu

Within a historical context, Japan’s Gojira was a product of nuclear devastation that terminated the country’s participation in WWII. An awesome and terrifying display of power, Godzilla was Oppenheimer’s gift to the world personified. Splitting the atom and attempting to master nature and harness its fruits has long been considered the height of human arrogance. In the original film’s interpretation, Godzilla was the result of that arrogance, and a brutal reminder that we humans are incredibly insignificant in the grand scheme of things. Godzilla is The Great Humbler, kicking the swagger out of our collective step and reasserting nature’s dominance.

Lovecraft, too, was wary of man’s brazen endeavors to aspire beyond our current reality. The sciences, he warned, could unleash horrors and inform us of far more than we want to know, including our infinitesimal place in the universe. In “The Call of Cthulhu,” Lovecraft features monstrous alien architecture that is “non-Euclidean”, the same type of mathematical wording that framed Einstein’s work on relativity. In H.P.’s world, men of learning often paid a terrible price for their curiosity and scientific ambition in stories like “The Colour Out Of Space” (don’t mess with glowing meteorites, folks), and rigid science itself was painted in a negative and ignorant light throughout Lovecraft’s short stories.

By no means am I calling Godzilla a modern-day Cthulhu. When it comes down to it, Godzilla, like most kaiju, is a fallible monster, while Cthulhu is acknowledged as a full-on cosmic entity, like most of the creatures in Lovecraft’s mythos. The people of Odo Island regarded Godzilla as a god, but it’s evident to the viewer that he isn’t. In fact, we see just how mortal he is by the end of the original Gojira film. Cthulhu and Godzilla are incredible beasts of differing cosmos. As such, it would be tough to claim that the former directly inspired the latter. I’m just pointing out that there are common themes, and as a fan of both realms, I find that, in and of itself, truly awesome.

Tags: Cthuhu, GODZILLA, H.P. Lovecraft, Horror, japan, Kaiju Week, Literature, World Cinema

No Comments