Since I was lazy and did not bother writing up day-by-day dispatches from Fantastic Fest like other, more professional Daily Grindhouse writers, I am only now playing catch up with my festival wrap up. Because this piece ballooned to such a ridiculous length, it will be posted in segments broken up to cover two days at a time. The following is part two.

Not surprisingly, given the fact that I watched five movies the day before and was up until 3:30 in the morning, I skipped the first block of films for day three. After sleeping in and getting some coffee and a couple of breakfast tacos (you can’t go five feet without someone trying to serve you a breakfast taco in Austin) down my gullet, I was ready to go for my first film of the day. And what a film it was.

DAY THREE

THE BRAND NEW TESTAMENT (2015, Belgium) is as heartfelt and breezy a film as you are likely to find that a large segment of the population would consider blasphemous. Needless to say, I fell in love with it almost immediately.

Ea (Pili Groyne) is the ten-year-old daughter of God (Benoît Poelvoorde). Yes, that God. Ea explains to the audience via voiceover that God is kind of a horrible being. He is abusive to her and her mother (Yolande Moreau). Bored and not good at anything else, he used his computer to create the world and all its inhabitants, just so he could have some new people to torture.

Ea had an older brother named J.C., but he was driven away by their father’s jealousy over J.C.’s ability to perform miracles. You can guess what happened when he ran off to Earth. God still gloats about that outcome to Ea and her mother.

After her father whips her with a belt, Ea decides she has had enough of him and turns to her brother for advice. It seems that J.C. is still able to communicate with her through the numerous statues of him placed around the family’s dingy apartment. J.C. advises her to escape to Earth like he did and gather her own apostles. Then she is to write a new New Testament, one that is about her apostles instead of her.

Before leaving, Ea breaks into her father’s office and releases the death dates for everyone on Earth. People receive these dates via text message, sending the world into a panic when deaths start syncing up with the dates and times released. Of course, with people learning exactly how much time they have left, many lose their fear of God as they realize that what they truly feared was death. Free to live their lives as they want, chaos becomes the order of the day.

It is into the chaos that Ea escapes. She takes her brother’s advice and combs Brussels for her apostles, eventually meeting six people who have all taken the news of their death dates in very different fashions. As she follows these six people, witnessing their interactions with others, Ea gently nudges them into situations that might maximize their happiness in the time they have left.

A film that could have rapidly descended into quirk overload at any second, co-writer/director Jaco Van Dormael walks a tonal tightrope that keeps THE BRAND NEW TESTAMENT endearing, honestly heartwarming, and very funny.

Van Dormael structures the film around the stories of each of Ea’s apostles, giving each one their own segments through the first two acts before cleverly converging them in the film’s final thirty minutes. Combined with two subplots—one of which involves God following Ea to Earth, and having a very different adventure than his daughter—and several running gags, the film can feel overstuffed at times. But even when it seems like Van Dormael is trying to keep too many plots going, it is an embarrassment of riches and not just filler.

Unfortunately, the next film in the day spent a good part of its first hour on filler.

HIGH-RISE (2015, United Kingdom) was another hotly anticipated film this year. The fifth feature film from Ben Wheatley, Britain’s reigning champion of bleak humor, it is an adaptation of the novel by J.G. Ballard. I am unfamiliar with the novel, but the script by Amy Jump, Wheatley’s wife and frequent collaborator, seems tailor-made for his obsessions with economic inequality in Britain’s unofficial but rigid class system.

Set in the’70s, the film tells the tale of the titular location, a modern residential building where the poorer residents (complete with loads of children) reside on the lower floors and the wealthy residents live on the upper floors. Into this glaringly obvious metaphor moves successful neurologist, Dr. Robert Laing (Tom Hiddleston).

Living on one of the upper floors, it initially seems that Laing should fit right in with the wealthy residents. But the other upper-floor residents treat him with barely veiled disdain. There are remarks made about his background that clearly indicate that the wealthier residents view him as someone who does not know his place due to his blue collar roots. But Laing, while feeling more welcomed by the poorer residents—including Richard and Helen Wilder (Luke Evans, Elisabeth Moss)—does not entirely fit in with them either. His neutral position allows him the perfect vantage point from which to watch the residents of the building turn on each other in increasingly savage and surreal ways.

The inevitable downfall of the building’s makeshift community begins believably enough. Residents on the lower floors are having issues with blackouts while upper floor residents complain that the lower floor residents are clogging up the garbage chutes with dirty diapers. From there, the stakes are gradually raised in the insular building.

Like current high-rise residences, the building in HIGH-RISE contains a grocery store and other amenities that are designed to be convenient for the residents. But with no reason to leave the building for anything other than work, the residents soon form an unhealthy community that is out of touch with the outside world. With adversarial relationships based on class standing, the residents of the building become more feral and desperate with every passing day, eventually forgetting the rest of the world exists and fighting for control of the building.

HIGH-RISE starts out promisingly as Wheatley uses Laing’s introductions to the various residents to serve as the same for the audience. Among those he meets are the building’s architect, Anthony Royal (Jeremy Irons); Charlotte Melville (Sienna Miller), a socialite without any discernible job; Charlotte’s son, Toby (Louis Suc), an apparent ten-year-old genius; and Robert (Tony Way), Royal’s thuggish assistant who delights in putting the screws to the residents of the lower floors. As these characters—and dozens of others—swirl in and out of Laing’s life, offering up different views of what the building is, where they stand in the hierarchy of their insular society, and how entitled/aggrieved they consider themselves, it quickly becomes clear that a fuse has already been lit before the film even started. The question becomes: when will the bomb go off? The answer is an hour—a very long and tedious hour.

Between the numerous character introductions that make up the first twenty minutes of the film and a pool party that signals the tipping point between a passive-aggressive society and full blown chaos, Wheatley indulges in a lot of wheel-spinning. If this forty to forty-five minute span of the film had included setting up some character beats that paid off down the line, I would have forgiven how slow it was. But this chunk of the film leads to nothing. Instead, it is a long stretch where characters lay out “the haves vs. the have-nots” theme of the movie in on-the-nose dialogue. The nightmare into which the film descends is fascinating and horrifying, but the story would have gone there without all the filler that Wheatley provides.

Even with all those complaints registered, the final forty-five minutes of HIGH-RISE are very good. Wheatley puts his surreal sense of humor and horror to good use, mixing sci-fi with paranoia, jet-black comedy, and queasy violence in a way that looks effortless but feels like being kicked in the head. By the time the residents are killing, raping, and possibly eating each other, the audience never pauses to consider how or why things have reached that level. It simply feels like the inevitable outcome of a society built on such massive inequality. It is a pity that the rest of the film does not live up to the third act’s sense of gut-instinct revulsion for how awfully people can and will treat each other if they think they can get away with it.

I honestly did not know what to expect out of GRIDLOCKED (2015, United States) the third film of the day. For the first fifteen minutes of the film, I slowly slid down in my seat as the film seemed to be an anemic rip-off of the mostly forgotten James Woods/Michael J. Fox flick THE HARD WAY. But then the film took some daring turns, defying expectations to become a fun, if derivative movie.

Hendrix (Dominic Purcell) is one of those badass cops that only exist in movies. With his shaved head, sour demeanor, and body that seems to have been chiseled out of concrete, he looks and acts like an angry Vin Diesel stunt double. Busting guys for simple possession on the streets of New York with extreme prejudice, it is clear that he has been trained for much more.

Brody Walker (Cody Hackman) is a petulant movie star with a few too many DUIs and assaults against paparazzi to his name. When his latest brush with the law threatens to actually land him in jail, he cuts a deal that finds him shadowing police officers to increase his respect for law enforcement—or some such movie ridiculousness. Not surprisingly, Hendrix is assigned to babysit Brody. Even less surprisingly, this assignment makes him even angrier than he already is.

Brody has the temperament of an excitable Chihuahua (and is not much larger than one, to boot) so his complaints about how boring Hendrix is quickly become as annoying to the audience as they do to the officer. So far, so generic.

But things take a turn when Hendrix takes pity on Brody after the latter reveals just how lonely his movie star lifestyle is. It turns out that Hendrix is the leader of an elite SWAT team. After a mission ended with him injured and the police psychologist refused to allow him to rejoin the team immediately, he was forced into his current job busting low-level criminals. To give himself and Brody a little bit of a pick-me-up, he takes the actor to where his old team is stationed to take part in some live-fire exercises (male bonding takes place over beers and guns in just one of the film’s many throwback nods to action films of the ‘80s and ‘90s).

Before Brody, Hendrix, or the SWAT team know what is happening, their remote headquarters is attacked by mercenaries wielding automatic weapons. While Hendrix and his team is able to fight off the first attack, they quickly realize they are trapped inside their building. As Hendrix tries to figure out what the mercenaries want at the same time that he tries to keep his team alive, he has to protect Brody who is equally frightened and excited to finally be seeing some real action.

I am not trying to blow GRIDLOCKED up to be a great movie, but it is fun. Co-writer/director Allan Ungar knows how to stage a gunfight for maximum excitement and casts his film well. Purcell’s facial expressions never change as he goes from stoic to barely repressed fury, but his grumpy demeanor works perfectly when placed up against Hackman’s hyperactive turn. Few things got a bigger laugh out of me at the Fest than Purcell’s grunting, monosyllabic responses to Hackman’s rambling questions and attempts at befriending him. Purcell’s deadpan delivery in these moments is flawless. Even better is Stephen Lang, hamming it up as the leader of the mercenaries. A legitimate badass in his own right (and an actor who adds legitimacy to this kind of indie action film), it is fun to see him square off with Purcell since their performing styles are so different, but so complimentary.

The film has some issues: it is too long by at least fifteen minutes; an unnecessary subplot about a potential traitor in the SWAT team’s midst lacks suspense; and Brody is largely forgotten about for much of the second act. But these missteps are outweighed by the positives (including a supporting role for Danny Glover, who gets to utter a very familiar line). I enjoyed GRIDLOCKED more than I probably should have, but it is hard to deny its ability to entertain.

The final film of the night was just as derivative as GRIDLOCKED, but thankfully, it was just as much fun.

THE MIND’S EYE (2015, United States) plays like the greatest hits from SCANNERS with most of the connective tissue of David Cronenberg’s film removed. In other words, it has lots of telekinetics and lots of bodies exploding and getting torn apart in creative ways.

Set in the early ’90s, the film opens as Zack (Graham Skipper), a powerful telekinetic is brutally knocked out and taken into custody by police in a small Connecticut town. Frightened by Zack’s power, the police call in Dr. Slovak (John Speredakos) to take custody of him.

It seems that Slovak runs a clinic where he claims to work with telekinetics to help them control their powers through a serum that dulls their abilities. Zack has no interest in working with Slovak or dulling his powers, but he goes along willingly when he learns that Rachel (Lauren Ashley Carter), a fellow telekinetic (who is also his ex-girlfriend), is at the clinic.

A few months later, it is clear to Zack that Slovak has no intention of letting him get close to Rachel. She is kept locked away in a different building on the clinic’s grounds, while Slovak taps her and other telekinetics for their spinal fluid in an attempt to make himself into an unstoppable telekinetic. When Zack stages an escape from the clinic and takes Rachel with him, Slovak sends Levine (Noah Segan), a telekinetic loyal to him, to bring them back. You can probably guess at the carnage that results from the ensuing battles.

THE MIND’S EYE is a really good midnight movie. Writer/director Joe Begos provides just enough characterization and plot to make the audience care about the graphic and creative violence on display. The cast has a field day with the material. Speredakos chews the scenery with gusto in his mad scientist role, Skipper has the intense telekinetic-drawing-on-his-power expression down cold, Carter uses her large, expressive eyes to spooky effect, and Segan commits to playing a sadistic, eye-patch wearing killer as though it has always been a dream role for him. The film even finds room for the omnipresent Larry Fessenden and THE BATTERY writer/director, Jeremy Gardner, in small but important roles.

But this film is all about the gore and capturing that ’80s low-budget, regionally produced horror film feel. Begos gets the look and tone just right and the gore is copious and satisfying as heads are lopped off and split in two, bodies are ripped apart, and a character goes through a transformation via some very gooey makeup effects.

Sure, THE MIND’S EYE is trash. But it is fun trash and that makes all the difference in the world.

DAY FOUR

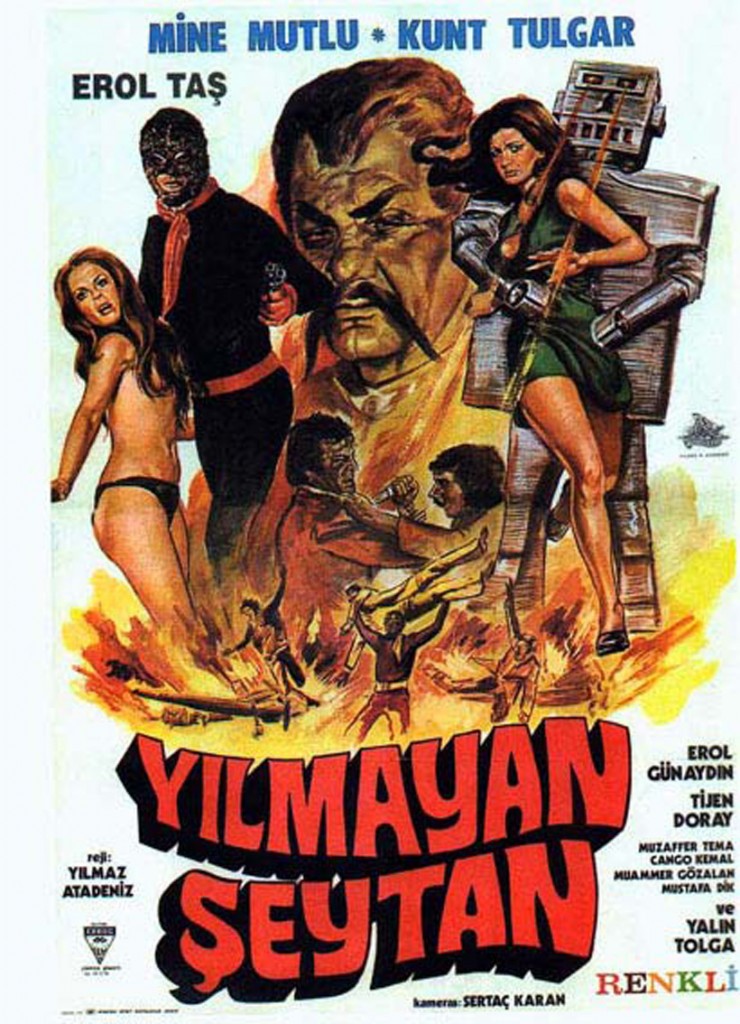

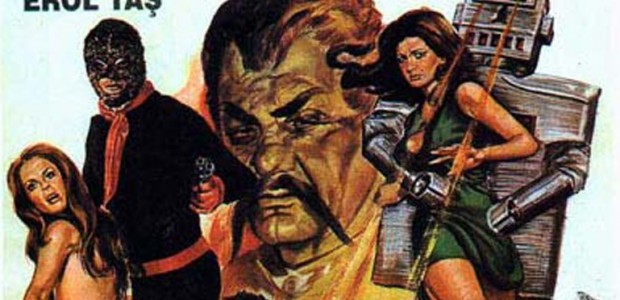

After staying for the late night screening of THE MIND’S EYE, it was a short turn-around to the next morning. Thankfully, the day was started off right with THE DEATHLESS DEVIL (1973, Turkey).

A part of this year’s celebration of Turkish exploitation cinema at the Fest, THE DEATHLESS DEVIL is pure, goofy fun that does not really need a review. It would be all but impossible to review the film in a traditional good/bad format anyway. All you need to know is that there are good guys, bad guys, a plot to destroy the world using remote controlled aircraft, a masked hero, insufferable comic relief, and the cheapest robot in the history of film. Combine these ingredients, mix in some actors who do their own insanely dangerous looking stunts, and bake with a thick layer of cheese on top, and you will come out with something that looks quite a bit like this film. I highly recommend it if you can catch it with an appreciative audience.

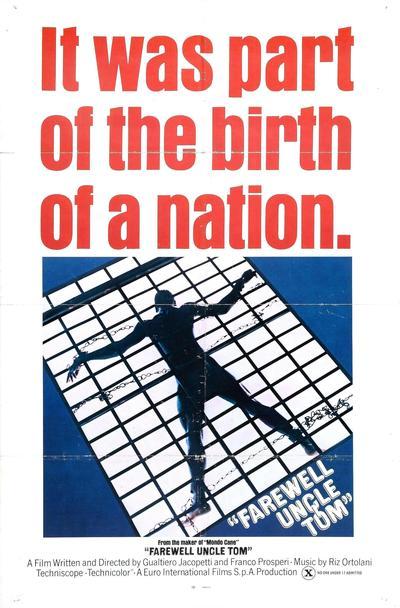

The next film was also a retro screening, but it was very different in tone and entertainment value. That previous sentence may be underselling just how vile and poorly put together a film FAREWELL UNCLE TOM (1971, Italy) is.

Written and directed by the team of Gualtiero Jacopetti and Franco Prosperi, FAREWELL UNCLE TOM was their attempt to bring their fake documentary style of filmmaking from their “Mondo” films to a story about America’s ugly history of slavery and racial inequality. But at every turn, Jacopetti and Prosperi undercut their supposed progressive interests in justice with scene after exploitive scene of men, women, and children being degraded in graphic recreations of the way slaves were abused in the years preceding the U.S. Civil War.

In a Q&A following the film, Nicolas Winding Refn (director of the PUSHER trilogy, BRONSON, VALHALLA RISING, and ONLY GOD FORGIVES) and film scholar Alan Jones struggled to explain why they wanted to show the film. Refn, given the chance to screen some selections found in his new book, THE ACT OF SEEING, on which he collaborated with Jones, chose FAREWELL UNCLE TOM largely because of the music. To be fair, the score by Riz Ortolani is a thing of beauty, but it feels so out of place with the disgusting images staged by the directors that it is all but impossible to enjoy it. By the time it came out that the film was made in Haiti under the dictatorship of François “Papa Doc” Duvalier, I was truly sickened. I have no idea how any serious filmmaker thinks they are able to make a film decrying slavery by using people who are basically slaves under a brutal dictatorship to recreate the horrors of such an institution. But I guess you have to hand it to the film, it is all but impossible for a movie to shock or morally disgust me any longer. This one did it without breaking a sweat.

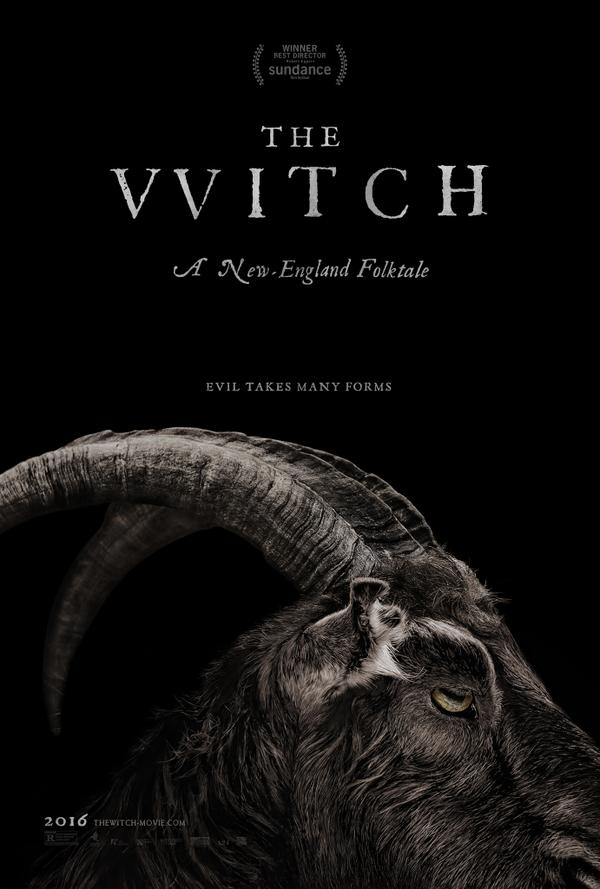

The next film was the debut feature for writer/director Robert Eggers. If THE WITCH is any indication, Mr. Eggers has a hell of a career ahead of him.

Set in the early 1600’s and subtitled “A New England Folktale,” THE WITCH is a raw exercise in the fear and paranoia that comes from mixing religious fundamentalism with an isolated existence.

William (Ralph Ineson), a devoutly religious man, is expelled from the Puritan community in which he and his family live. Believing the local Church is teaching a watered-down version of the rigid Christianity to which he adheres, William is only too happy to leave. But his family is not so sure that going off to live in the wilderness is the best of ideas.

William’s family consists of his wife Katherine (Kate Dickie), a teenage daughter named Thomasin (Anya Taylor-Joy), thirteen-year-old Caleb (Harvey Scrimshaw), twins around six years of age named Mercy (Ellie Grainger) and Jonas (Lucas Dawson), and a newborn baby boy.

Katherine dotes on all of her children except for Thomasin. A very pretty girl on the verge of becoming a beautiful young woman, Thomasin seems to threaten Katherine. Is the mother jealous of her daughter’s beauty? Is her reaction simply a puritanical fear of Thomasin’s blossoming sexuality? Or is there something other-worldly about Thomasin that Katherine senses?

Despite his righteous rhetoric when being expelled from the community, William proves to be a level-headed and loving father. He sees the unfair treatment that Thomasin receives from Katherine and tries to balance things out with extra kindness toward his daughter. Of course, this kindness does not go unnoticed by the brittle Katherine, giving her one more reason to treat Thomasin as though inferior to the rest of the children.

When Thomasin is playing with her newborn brother near the edge of the woods, he suddenly goes missing. Despite William and Caleb searching high and low, they are unable to find the baby. Katherine is inconsolable and turns every last bit of her negative attention toward Thomasin, despite William’s repeated belief that a wolf most likely snatched the baby.

But Thomasin is positive that there was no wolf since the child was taken right out from under her nose. Filled with stories from their father and the church about the devil and witchcraft, she is the first to suspect that her little brother was taken by an evil supernatural force. Unfortunately for her, Thomasin is not the only one in the family that comes to believe this and it is not long before Katherine starts pointing her finger at her. With their crops failing and Winter closing in, madness threatens to destroy the family as others start accusing Thomasin of witchcraft with only the increasingly overwhelmed William holding on to his wits and his belief that God will help the family turn things around.

For most of the film’s very tense ninety minutes, Eggers builds and releases suspense by playing on the ambiguity of family’s situation. Despite including a short scene that seems to show the baby being prepared for sacrifice by an unseen figure, much of the film’s first hour leaves the audience wondering if that moment was simply the fever dream of one of the characters after having such stories hammered into their head from the time they are old enough to comprehend what they are being told. And while the explanation of a supernatural evil could explain such things as the crops dying, the baby going missing, or the menacing behavior of Black Phillip, the family’s goat, these problems could simply be chalked up to William being an incompetent farmer, the baby actually being snatched by a wolf, and that goats are natural jerks. The answers are never clear cut, a fact that ratchets up the tension in THE WITCH as Eggers finally allows all hell to break loose in the third act.

While Eggers gets instant atmosphere by painstakingly recreating the era through costuming and the farmhouse set, much of the credit for how well the film works has to go to the stellar cast. Taylor-Joy ably garners audience sympathy as a young woman who is not sure just how or why she has engendered such scorn from her family. Dickie brings shading to her alternately crazed and pointedly mean portrayal of Katherine. Grainger and Dawson make for the creepiest and most obnoxious pair of kids I have seen in a film in a long time, which means they succeeded handily in fulfilling their purpose in the story. But it is Ineson and Scrimshaw who steal the movie as the two characters least likely to give in to the histrionics of the increasingly awful situation, but who are also the least able to stop what is happening.

I came very close to loving THE WITCH. There is a moment late in the third act that would have been a perfect ending for the film. Unfortunately, Eggers makes the choice to wrap up the film’s plot threads in a neat bow, largely erasing the ambiguity that worked so well until that point. This ending does not take anything away from what came before it, but it does feel like a slight cheat on the part of the young filmmaker. But even with that complaint, THE WITCH still remains one of the best and most powerful films I watched at the Fest.

After THE DEATHLESS DEVIL and THE WITCH, the inadvertent satanic theme continued with THE DEVIL’S CANDY (2015, United States).

Jesse (Ethan Embry) is a struggling artist living in Austin, TX with his wife Astrid (Shiri Appleby) and their thirteen-year-old daughter Zooey (Kiara Glasco). Like a lot of young parents in their thirties, Jesse and Astrid have tried to maintain their youthful passions while trying to responsibly raise their daughter.

Jesse, in particular, does not seem to have aged beyond his early twenties. Heavily tattooed, sporting long hair and a thick beard, listening to heavy metal while he paints, Jesse is trying very hard to hold on to his youth while cautiously eyeing middle age. In a concession to the needs of raising a child, he has taken on a commission from a bank for a large canvas painting of butterflies. Both he and Zooey find this development amusing, but Astrid looks at it as a sign of growth for Jesse.

Believing that better days are around the corner, Jesse and Astrid look at a large suburban house for sale at a tempting asking price. By the time they learn that the elderly woman who used to live there died in the house, they are too in love with it to pass up the offer.

What no one seems to know is that the woman did not die peacefully. She was murdered by Ray (Pruitt Taylor Vince), her brother who also lived in the house and heard voices telling him to kill. Ray tried to drown out the voices by playing loud metal music on his guitar, but that stop gap measure only worked for so long. After the deaths, Ray was left on his own. Frightened, confused, and homicidal, all Ray wants to do is return home. This is, of course, bad news for Jesse and his family.

The first hour of THE DEVIL’S CANDY largely feels like a movie that is trying to find itself. There are elements of the supernatural with the voices that Ray hears and that Jesse eventually starts to hear as well after moving into the house. But while Jesse does start to behave erratically (he turns the butterfly painting into a nightmarish hellscape that includes an image of Zooey in flames) upon hearing the voices, he never becomes an active threat to himself or his family. Instead, the pitiable, but frightening Ray is shown kidnapping and murdering children in the area before skulking around the house, fixating on Zooey. As Jesse’s odd behavior strains his formerly close relationship with Zooey, writer/director Sean Byrne throws in a dash of kitchen sink melodrama for good measure.

None of those elements or how they are presented in the film’s first two acts are a problem. But they never actually become a cohesive whole. Is it a film about satanic possession? Is it a sensitive drama about a father losing his bond with his daughter? Is it a serial killer thriller about an unstable man who has the protagonists in his crosshairs? It is all of these films, but never at the same time. This is a problem that Byrne never quite solves.

Maybe that inability to fully settle on a tone or storyline is why I enjoyed the third act so much. Byrne largely chucks the various plot lines in favor of an over-the-top climax and ending that includes an impressive sequence of Ray’s assault on the house that is violent and ridiculous in the best way possible. A final battle in a room choked with flames and smoke, making the idea of a descent into hell almost literal is just the icing on the gratuitous cake. Instead of feeling jarring when compared to the relative restraint of the first two acts, this ending made me want to stand up and cheer. At several points in the film, Byrne threatened to be a little too precious with his storytelling. When he finally let things fly, I realized that element of fun and flat-out excess was what had been missing from THE DEVIL’S CANDY.

Despite the third act pyrotechnics, I still am not sure I can call it a good film, but THE DEVIL’S CANDY does send the audience out into the lobby on a high. Take that measured recommendation how you will.

The final film of the day was not at all what I expected it to be.

OFFICE (2015, South Korea) is a satire about overworked office drones masquerading as a deliberately-paced thriller that in turn is masquerading as a horror film. That is an ambitious trick to pull off and director Won-Chan Hong is largely successful. The question is, do all those layers make for a good film?

Kim Byeong-Gook (Sung-Woo Bae) is a milquetoast worker stuck in middle management at a marketing firm. As the film begins, he returns to his home and murders his wife, child, and elderly mother with a hammer.

The next day, the police, in the person of Det. Jong-Hoon (Sung-Woong Park), descend upon Kim’s office, much to the dismay of the firm’s director (Eui-Sung Kim). Interested only in keeping his firm’s name out of the papers in association with the crime, the director is only as cooperative with the police as he has to be. Most of the other workers in the office follow suit, describing Kim in only the most generic of terms.

But the detective senses something very wrong with the reactions of the workers. His suspicion is confirmed when he wishes to question Lee Mi-Rye (Ah-sung Ko), a mousy young intern. Before letting her talk to the detective, the director pulls Lee aside and warns her not to refer to an unstated incident that occurred between her and Kim. But Lee is not a very good liar and it does not take long before the detective has zeroed in on her as the person in the office who may know why Kim murdered his family and where he might be hiding.

OFFICE takes its time getting to where it wants to go. The hunt for the killer takes on a little more urgency when Kim’s co-workers start getting bumped off one by one, but the film is more concerned with exploring the poisonous working atmosphere that so many office workers put up with. Sometimes this aspect of the film is hilarious (the director’s tirades in meeting after endless meeting are a highlight), but more often than not, these scenes are like watching a squirm comedy with the comedy taken out of the equation. The way poor Lee is treated with open scorn makes for uncomfortable viewing because she is so sympathetic and undeserving of such vitriol. If anything, the film proves to be too adept at presenting a typical office job as a place of despair.

That leaves the horror/thriller elements to keep the film engaged with the audience. While these scenes sometimes connect (Kim’s murder of his family, a terrific stalking sequence in a stairwell), they are spaced out too far apart between endless scenes of Lee enduring a particularly hostile work environment. The film quickly becomes as oppressive to the audience as it does to its characters.

There is technically nothing wrong with OFFICE. It’s well-acted, beautifully shot, and when the suspense is cranked up, it actually does provide some jolts. But those jolts do not come often enough and the long sequences of office satire eventually let the air out of the film. But for better or worse, Won-Chan Hong seems to accomplish exactly what he wants to do with the film.

In the next installment, more retro Turkish fun, the satanic theme continues, a promising bit of German weirdness falls apart, and an ambitious director tries to help 35mm film make a comeback.

— MATT WEDGE.

Tags: Allan Ungar, Amy Jump, Austin, Belgium, Ben Wheatley, Benoît Poelvoorde, Cody Hackman, Danny Glover, Dominic Purcell, Elisabeth Moss, Ethan Embry, Fantastic Fest, Film Festivals, Franco Prosperi, Gualtiero Jacopetti, J.G. Ballard, Jaco Van Dormael, Jeremy Irons, Joe Begos, Lauren Ashley Carter, Louis Suc, Luke Evans, Matt Wedge, Pili Groyne, Riz Ortolani, Robert Eggers, Screenings, Sean Byrne, Shiri Appleby, Sienna Miller, South Korea, Stephen Lang, Sung-Woo Bae, Sung-Woong Park, Texas, The UK, Tom Hiddleston, Tony Way, Trish Stratus, Turkey, Vinnie Jones, Won-Chan Hong, Yolande Moreau

No Comments