It feels necessary to say this up front: I’m not sure GLADIATOR II is a movie meant for me. I am a rare breed in that I’m a Roman history nerd who’s actually read the histories. I’m conversant in Suetonius, Cassius Dio, Tacitus, and Gibbon, to say nothing of Paterculus or Josephus. I can go on at length how Tiberius probably didn’t have minnows at Capri, but Nero did play the lyre while Rome burned (he thought it would raise morale). I can name the Roman Emperors who weren’t the manly white men who occupy the fevered dreams of the manosphere (hint: there were a lot). All of this is to say, I can spot the BS in a Roman movie, and I’m not hesitant to call it out, much to the annoyance of most people who’ve met me.

Often, those inaccuracies can be overlooked in the name of narrative requirements. They can even be charming. I, CLAUDIUS remains a classic piece of melodrama (how RuPaul’s Drag Race and the wider LGBT community haven’t embraced it yet is beyond me). I’m willing to forgive a lot in the way of historical inaccuracy if my historical entertainment is… well, entertaining, and if there are at least some concessions to historicity. To paraphrase menswear maven Alan Flusser, there’s an artform to showing you know the rules but chose to break them anyway. GLADIATOR II commits the dual sins of not only being a fairytale version of the Roman Empire with little in the way of historical verisimilitude, but a bloated, anemic imitation of its predecessor.

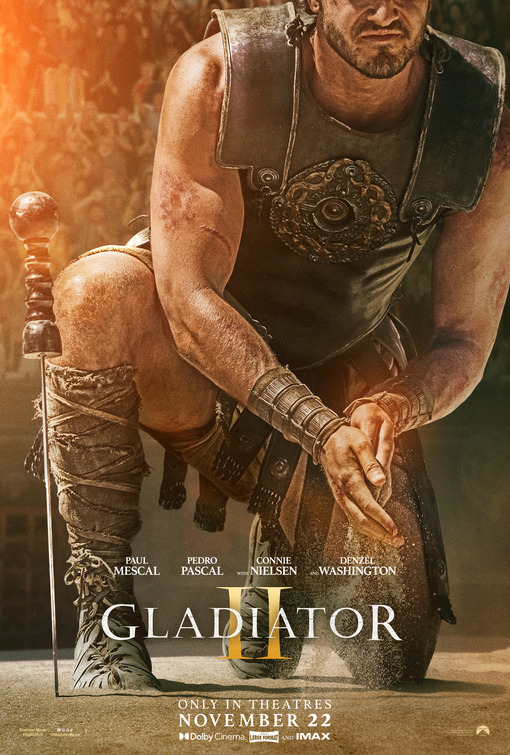

Lucius (Paul Mescal in a dead-eyed and quite frankly, disturbing performance), grandson of Marcus Aurelius, has been living in hiding in North Africa since watching Maximus shank bad uncle Commodus. Having put the bloody politicks of Rome far behind him, he’s settled into life as a member of a Numidian tribe and started a family of his own. That idyll is shattered when the Empire comes a knockin’ in this film’s version of the original’s opening Germanic battle, flipping the perspective so our allegiance is with the “barbarians” rather than ambivalent General Acacius (Pedro Pascal). Of course, Acacius is successful, and Lucius is rounded up to be taken back to Rome as a slave, where he’s purchased by social-climbing “sports promoter” (read: gangster) Macrinus (Denzel Washington).

As Macrinus explains, he has designs on some imperium of his own, and intends to use Lucius as his tool to achieve it. See, since Commodus’ downfall, Rome has inexplicably fallen into the hands of Geta and Caracalla, a pair of feral gingers who’ve pushed the Empire to the brink of famine by expanding its borders beyond their means. Macrinus has worked long and hard to win the gruesome twosome’s favor, positioning himself to usurp power should they ever fall- a fall he intends to orchestrate by weaponizing Lucius’ hatred for the Empire that killed his wife. Does it matter that Acacius is secretly a war-traumatized altruist who wants to restore the Republic? Does it matter Lucius is about to learn he’s secretly Maximus’ illegitimate son from a long-ago affair with Marcus Aurelius’ daughter Lucilla (a returning Connie Nielsen)? Do we care?

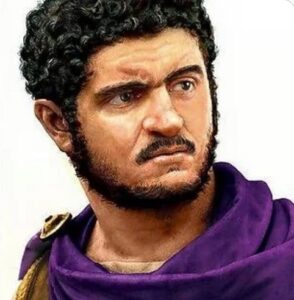

First things first: GLADIATOR II proudly builds its core plot points on elements of total historical fiction. While GLADIATOR paid homage to the broad strokes of history, GLADIATOR II doesn’t seem like it can even read history. Caracalla and Geta were, in fact, briefly co-emperors, the heirs of Rome’s first African Emperor, Septimius Severus, and his Syrian wife Julia Domna (why they’re played by a pair of Ed Sheeran clones in the age of representation is beyond me). At the time of the film’s action, though, Severus was still in the middle of his stable reign, and wouldn’t pass rule to his sons for another eleven years (Caracalla served for a period as his protege/co-Emperor).

Empress Julia Domna and Emperor Septimius Severus

Geta didn’t last long after daddy’s death, though, and in short order was murdered by his own power-hungry brother (right in front of their mom, no less). Rather than the syphilitic, monkey-loving mess Caracalla is here, it’s better to think of him as Breaking Bad’s Tuco Salamanca given unlimited geopolitical powers. In contrast to Acacius’ exhaustion with conquest, Rome had long ago consolidated its realm. That occurred nearly 100 years prior to the action, in 117, under Trajan; from his successor, Hadrian, forward, Roman conquest essentially ceased in favor of border security. Even Caracalla recognized the futility of attempting to expand the Empire. That left the wannabe-Alexander the Great to stage bloody raids on his own (peaceful) cities before one of his bodyguards put him out of his misery by stabbing him in the crotch during a roadside whiz (unfortunately, there is no crotch-stabbing to be had here).

Pictured: NOT Ed Sheeran (Artist Unknown; Contact For Credit!)

On the one hand, the flagrant disregard for history is galling. On the other, the film’s characterization of the brothers provides some of the most enjoyable moments, as director Ridley Scott is clearly drawing on the pageantry and high camp of I, CLAUDIUS. That’s especially true for Joseph Quinn as Geta, who isn’t so much portraying an original character as he is playing John Hurt playing Caligula in CLAUDIUS. All bad pancake makeup, giddy bloodlust, and mincing glee, he is living his Roman Emperor as homicidal drag-queen fantasy, and I was there for it. It’s a performance that’s essentially split between Quinn and Fred Hechinger’s slightly more down-key Caracalla. Dick rot aside, the pair are so interchangeable that when one exits the film ¾ through it’s barely noticeable, or even important. Why Scott and screenwriter David Scarpa didn’t opt to consolidate the pair into one Emperor is beyond me, other than to give us a truly memorable sequence (itself another CLAUDIUS shout-out) involving Macrinus, a severed head, and a rightly terrified senate. (Speaking of CLAUDIUS, Derek Jacobi reprises his GLADIATOR role as Senator Gracchus, for no other reason than Derek Jacobi is functionally immortal at this point and probably obligated to appear in every piece of Roman Empire media, lest his portrait begin aging).

Which brings us to Macrinus, another one of Rome’s underrepresented Emperors. The first Berber on the throne, Macrinus was here for a good time, not a long time. It’s not exactly a spoiler to say his reign was neither long nor auspicious, but reign he did, and his rapid rise and fall from power are worthy of their own movie. Only Washington seems aware of that, though. Bedecked in the 200 CE equivalent of DeNiro’s CASINO wardrobe, Washington owns every one of his scenes in a performance that’s one part Tony Curtis in SWEET SMELL OF SUCCESS, one part Rudy Ray Moore’s CANDY TANGERINE MAN, and one part Jack Nicholson in THE DEPARTED. Washington oozes charismatic sleaze and righteous indignation, and his bloody-pragmatism-to-a-fault perspective on how to run a fragile empire makes for some of the movie’s most thought-provoking moments. Rather than focus on him, though, the film is compelled to relegate him to the sidelines until a climax that apes the ending of LETHAL WEAPON while also giving a historical domain character a laughably ahistorical fate.

And here we approach the fatal flaws of GLADIATOR II. In giving us Lucius as a protagonist, we’re saddled with a legacy hero who’d just entered puberty the last time we saw him, and who’s somehow gotten less compelling since. All bug-eyed vengeance and anti-charisma, Lucius is a copy-of-a-copy of Russell Crowe’s Academy Award-winning turn as Maximus. Crowe is an actor who knows a stellar performance can be delivered with an economy of speech. When his Maximus did monologue, it was to give us profound insight into a silent but deep man of profound love and conviction. Lucius, conversely, is a pissy Robert E. Howard/Edgar Rice Burroughs wannabe, full of rage and little else — to the point Macrinus explicitly reminds the audience of this every few scenes, as if to hand-wave the paucity of characterization. Even then, a totemic arrow quill he keeps as a symbol of his wrath ultimately comes to naught after being positioned as a Chekov’s Gun (though we do get to see him bloodily choke out a mediocre CGI simian, so there’s that).

His protestations about the corruption of Rome ring hollow and cliched, especially for a character who hasn’t interacted with it in a decade-plus. In a bit of finessing the Romans themselves would approve of, the movie has to stoop to syncretizing Lucius with Maximus in the final act in an effort to get us on his side, literally putting him in Crowe’s costume. That’s a major problem, because not only do Lucius’ anti-Roman proclamations make up the bulk of his dialogue, but they rather form the thesis — or what wants to be the thesis — of the movie: Rome may never have been great, but it could be great, if the right people will stand up and fight for it.

It’s a ham-fisted, hastily reverse-engineered anti-MAGA message that falls flat for its utter lack of conviction. For one thing, it’s a conceit betrayed by one of the film’s truly remarkable achievements, which is its visual depiction of Rome. Rarely has the glamorous squalor of the Eternal City come so alive onscreen, and the audience gets a true idea of what it would have looked like to walk the streets of the crowded, stinking, shining epicenter of the Empire. It’s a sight to behold, one that helps underscore a truism about Roman history the aforementioned manosphere likes to sweep under the (presumably Persian) rug: the Empire was an incredibly diverse and integrated creature, obsessed with class but unconcerned with race or ethnic origin. It was a place in which social mobility was as achievable for the sons of a low-ranking senator as it was for an African tradesman or Spanish equestrian in from the hinterlands. Even the movie has to stop for a moment and consider its own message, in a scene that speaks to the fascinating exploration of Roman society the film could have been. Ravi, an ambiguously Greco-Indian doctor who befriends Lucius, explains why he refuses to leave the Empire by way of laying out its complex and startlingly modern social dynamics. Ravi came to Rome, learned the language, and has a job he likes; he married a Roman-Briton woman, and their children are mixed race. He and his family are Roman. It’s Emma Lazarus’ New Colossal dream realized, 200 CE style — but, as far as our hero Lucius is concerned, it’s all bullshit.

The Romans themselves were constantly bemoaning how far their society had fallen; the whole point of Saturnalia was to celebrate Rome’s imaginary golden age and how they would never experience it again. It’s no surprise, then, that — as a distinctly Amero-British subgenre — Roman Empire movies are chronically fixated on themes of honor and loyalty to a quasi-Republic predicated on military dictatorialism and populist appeal. While “Restoring the Republic” is a stock plot in these stories, though, here it’s just a vague pretext for why different characters want to kill one another, and why we get an almost smackdown between warring legions. While the original GLADIATOR was a moving character study and mediation on American Empire at the turn of the Millennium, GLADIATOR II is a weak wannabe trading on residual goodwill. It brushes up against topical relevance and entertaining characters, only to fall back on hackneyed platitudes that do little more than serve as Rorschach tests of the audience’s political leanings.

Bad movies can be forgivable if they’re fun. Long movies can be tolerable if they’re entertaining. Historically inaccurate costume dramas can be engaging if they deliver on spectacle. GLADIATOR II, in swinging for the cheap seats of the Colosseum, fails on every count. At 2.5 hours, it’s an endurance test that will please audiences wanting sword-and-sandal action but few others. If nothing else, we’ll at least always have Macrinus, the Twins, and their monkey. Now, someone, please show this and I CLAUDIUS to RuPaul. If it doesn’t succeed in anything else, maybe GLADIATOR II can finally inspire my Roman Glampire maxi-challenge.

Tags: Action Film, Alec Utgoff, Alexander Karim, Claire Simpson, Connie Nielsen, David Franzoni, David Scarpa, Denzel Washington, Derek Jacobi, Fred Hechinger, Harry Gregson-Williams, History, John Mathieson, Joseph Quinn, Lior Raz, Matt Lucas, Monkeys, Paul Mescal, Pedro Pascal, Peter Craig, Peter Mensah, Ridley Scott, Rome, Rory McCann, Sam Restivo, Sequels, Tim McInnerny, Yann Gael, Yuval Gonen

No Comments