Happy All-Hallow’s Month! In anticipation of Halloween — which, let’s face it, we’ve been anticipating since last Halloween — Daily Grindhouse will again be offering daily celebrations of horror movies here on our site. This October’s theme is horror sequels — the good, the bad, the really bad, and the unfairly unappreciated. We’re calling it SCREAMQUELS!

And if you like this feature, please check us out on Patreon for unique reads and deep dives! Just $3 a month gets you everything! All treats, no tricks.

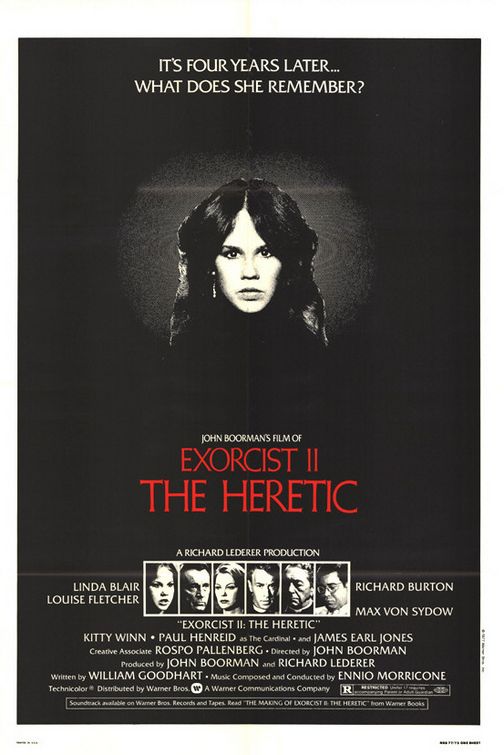

Perhaps one of the more under appreciated aspects of 1970’s Hollywood is the way it revolutionized the sequel. During a decade where numerous films were being made that broke any number of conventions, several sequels stretched the definition and expanded the potential of the form, moving away from mere expected serialization. These experiments were met with varying responses, of course — audiences weren’t exactly thrilled with the bleak nihilism of BENEATH THE PLANET OF THE APES (1970), but adored the richness of THE GODFATHER PART II (1974), for example. EXORCIST II: THE HERETIC, a sequel to the 1973 horror film about demonic possession that was so successful it had become “a classic in its own time” (as one early teaser for THE HERETIC aptly put it), was met with arguably the most vehement and violently negative response of any sequel of the ‘70s. According to various sources (such as director John Boorman and THE EXORCIST director William Friedkin, who aggressively disowned the sequel), audience response to THE HERETIC ranged from derisive laughter to full-on rioting, with one preview audience supposedly chasing Warner Bros. executives down the street during the screening. Critics were just as savage toward the film, trashing it in their reviews and columns while calling for everyone involved with it to be shamed. Clearly, Boorman’s experimentation with the material hadn’t worked.

At least, it didn’t work then. When viewed now, THE HERETIC is something of a minor revelation, a sequel that is almost completely its own film, unconcerned with fan service or franchise building or any form of lazy pandering. As more distance is gained from this film and other notorious works like ZARDOZ (1974), John Boorman is seen less as a pretentious maker of unintentional camp and more like a misunderstood auteur, an artist struggling (and not always completely succeeding) to use cinema to make grandiose, unique statements on the human condition. Warner Bros. were certainly thinking of Boorman’s award-winning feature DELIVERANCE (1972) as opposed to ZARDOZ when they approached the Englishman to helm their EXORCIST sequel. Boorman was still clearly in ZARDOZ mode, however, his imagination sparked by the many theological and philosophical questions within the original EXORCIST.

The original plan by producer Richard Lederer for EXORCIST II was to make a more obvious sequel, one that would follow Detective Kinderman (Lee J. Cobb in the original EXORCIST) as he investigated the still unsolved (in legal terms) deaths from the first movie. After Cobb’s passing, Lederer looked to Boorman, who had been approached years before to potentially make THE EXORCIST. However, he viewed the original novel by William Peter Blatty as a story about the abuse of a young girl, and thus had no interest in merely repeating the first film either with Linda Blair’s Regan or another character. When Boorman was given an initial screenplay by playwright William Goodhart, however, he was enthused at Goodhart’s taking the story in a metaphysical direction, and signed on. Boorman and his filmmaking partner, Rospo Pallenberg, went to work on the script as they hired cast and crew and began shooting. The writing-while-filming situation was only one aspect of the film’s production that was troubled, with problems ranging from star Blair continually showing up late to director Boorman falling ill.

These well-documented issues undeniably contribute to the film’s reputation, and not helping matters is its bizarre release and subsequent recutting. Just days after the movie’s disastrous opening in a few cities, Boorman recut the picture in a shorter version for wide and international release. These cuts weren’t just for clarification, but reactions to moments that the studio (and possibly Boorman himself) found audiences rejecting. Thus, while the full 117-minute version of the film has its flaws, the 102-minute recut is barely watchable, a hodgepodge of sloppy editing rhythms and bizarre attempts to take all the flavor out of the movie while trying to retain some feeling of the original EXORCIST (a strategy which sees clips of the first movie awkwardly and obviously edited into THE HERETIC). The original version of the film contains a good deal of symbolism and narrative depth that the shorter version steamrolls over, culminating in an ending that feels so embarrassingly truncated it’s like the movie itself is rushing out the door. This compromised version of THE HERETIC was the most widely available for years, and it’s an early example of Hollywood mainstream filmmaking’s discomfort for the metaphysical. (About a decade later, the sequels POLTERGEIST II: THE OTHER SIDE (1986) and POLTERGEIST III (1988) would suffer a similar fate; the reasons why in those cases were varied, of course, but it’s telling that all three movies deal with similarly heady subject matter and outsized ambitions.)

Fortunately, Boorman’s original theatrical cut of THE HERETIC has now supplanted the shorter cut on home video and streaming, just in time for its reappraisal. So as not to end up feeling like those alleged rioting audiences back in 1977, the key to appreciating THE HERETIC is to accept the fact that Boorman, Goodhart and Pallenberg are at no point attempting to make a horror movie with their film. Where the original EXORCIST gains its ferocious, terrifying power from presenting everything as grounded as possible, THE HERETIC flies off — literally — into questions about the existence of the supernatural and the ongoing struggle between Good and Evil. To put it simply, THE EXORCIST is reality; THE HERETIC is fantasy. Boorman, soon to adapt the Arthurian legends to the screen in 1981’s EXCALIBUR, tells the story of Father Philip Lamont (Richard Burton) and his Vatican-mandated investigation into the demise of Father Lankester Merrin (Max von Sydow) with an operatic scope and mystical flourishes. Lamont’s investigation takes him to Regan, now in her late teens, who is under the psychiatric care of Dr. Gene Tuskin (Louise Fletcher). Regan purports not to remember any of her possession experience (as she had claimed at the end of the first film), but Lamont and Tuskin aren’t so sure, and they use a device they call a “synchronizer” to test that theory. The synchronizer (essentially a plunger with some beeps and flashing lights, meant to visually and aurally evoke a heartbeat) connects two subjects via hypnosis, allowing linked people to share visions, journey into the ether of the past, and more. Through this process, Lamont and Tuskin learn that the demon Pazuzu still lurks within Regan — not to possess her again in the same way as before, but to prevent her from realizing her full potential of Goodness. Regan, the film argues, is a person with great power, and her experience with Pazuzu has unlocked that potential, making her one of a growing number of individuals on the planet who hold the key to humanity’s evolution.

As one can see, these are remarkably outsized concepts for any film, let alone one that’s a sequel to a movie that is, by contrast, brutally single-minded. If THE EXORCIST, by Friedkin’s assertion, is a story about the mystery of faith, THE HERETIC is a story about the mystery of the supernatural and its potential effects. Religion plays much less of a factor in this film than the original — it’s replaced with the movie’s own mythology about how technology and psychology can effectively open individuals up to perceiving the supernatural. Ironically, Goodhart took his inspiration for these ideas from the theories of the real-life Jesuit priest and archeologist Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, who was also the inspiration for Father Merrin’s character in Blatty’s novel. Boorman and Pallenberg take these concepts and run with them, pitching the idea of Regan as a “good locust” who evil entities like Pazuzu are drawn to in order to try and corrupt her or at least diminish her. The film uses locusts as its primary symbol thanks to their dual nature—the creatures can be either “happy-go-lucky grasshoppers” or a cannibalistic hive mind, as James Earl Jones’ Kokumo cheerfully explains in one scene. Each character in the film has their Good and Evil sides examined, showing how everyone contains the capacity for both, a choice that makes the film remarkably nuanced while contributing to it feeling unresolved by the end. Boorman even makes sure to call the existence of the supernatural into question: in one early scene, Regan demonstrates to Sharon (Kitty Winn) how she can fake bending spoons, and the director leaves little hints that Regan, Lamont and eventually Gene may be perceiving events differently than others around them. THE EXORCIST acts as a rational argument for the existence of the beyond, while THE HERETIC leaves a ton of room for the audience to make up their own minds.

Ultimately, there are probably a few too many oddities and loose ends for EXORCIST II to ever be fully heralded as an unsung masterpiece. Everything from Boorman’s quirks (Regan takes up tap dancing!) to the film’s uncomfortable continuity with the first movie (a stand-in is used for Linda Blair in demon makeup, the absence of Ellen Burstyn’s Chris MacNeil is explained away in a few lines of dialogue, and Jason Miller’s Father Karras is never mentioned once) keep it from being a great sequel. The numerous compromises made in the movie—before one even considers the botched re-edit — makes it an uneven experience. Yet the fact remains that it’s one of the few sequels to really branch out from its predecessor in big, bold fashion, making it feel utterly unique in today’s increasingly cookie-cutter landscape of franchises and cinematic universes. In a way, its poor reputation is poetically fitting: like the real-life figure whose theories it was inspired by as well as its ironically self-fulfilling prophecy of a title, EXORCIST II is a heretic of a sequel.

Tags: Dana Plato, Ennio Morricone, Horror, James Earl Jones, Kitty Winn, Lee J. Cobb, Linda Blair, Louise Fletcher, Max Von Sydow, Ned Beatty, Paul Henreid, Richard Burton, Richard Lederer, scream factory, Sequels, The 1970s, The Devil, Tom Priestley, William A. Fraker, William Friedkin, William Goodhart, William Peter Blatty

No Comments