As I sit here writing this, the 11th Circuit Court of Appeals has stayed a federal district court decision blocking enforcement of Florida laws banning gender affirming care for minors and severely limiting it for adults. The fight over Florida’s SB 254 is winding its way toward a hostile and politicized US Supreme Court, disinterested in human rights or dignity. The 11th Circuit’s decision has turned trans people who can afford to move into refugees within their own nation.

Much of the summer was spent with the world embroiled in a gender witch hunt at the 2024 Paris Olympics. Algerian boxer Imane Khelif entered the Olympics as a target of harassment and abuse, because IBA President Umar Kremlev accused Khelif of having XY chromosomes and being unfit for IBA sanctioned women’s competition. Khelif didn’t have the funds to fight the IBA sanction, and so then entered the Olympics the target of transphobic shitbags like Elon Musk and J.K. “Black Mold” Rowling. After the tearful second round concession of Angela Carini, bigots felt emboldened. Twitter was rotten with screen grabs of Khelif with clumsy arrows between her legs or at her throat, to identify so-called hidden secondary gender characteristics. Sniveling rat-fucks called for Khelif to submit to public chromosome testing. Regrettably, many well-meaning people entered the argument responding with the point, “She was born a woman,” unaware that if they argued the point and not the framing of the argument, they were essentially ceding a point to gender essentialists.

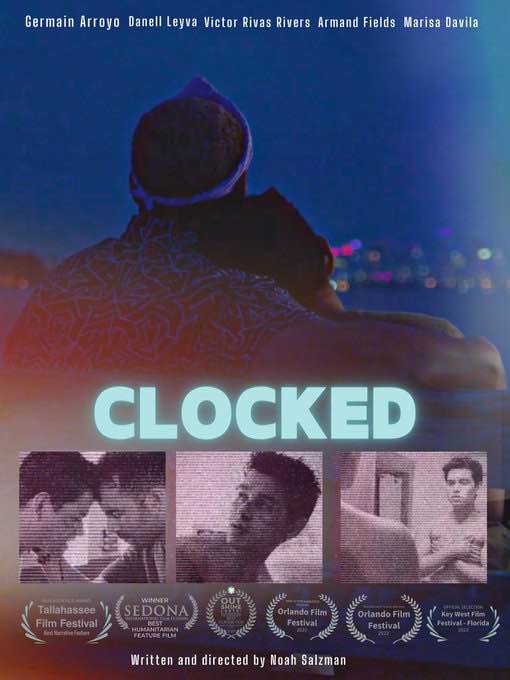

So it is with the tumult in Florida and the bigoted witch hunt centered around boxing that I sat down with Noah Salzman’s CLOCKED. Salzman reached out to me to take a look at the film after my review of Jennifer Esposito’s FRESH KILLS was published. At first, I didn’t understand the through line between the two films, and why Salzman would want me to watch it based on my perspective on FRESH KILLS, but as the film unspooled, it became clear. Central to both films is the absolutely crushing weight of expectations experienced by second- and third-generation immigrant children. The daughters in FRESH KILLS find themselves unable to escape their family’s mafia ties, misogyny, and Catholicism, and CLOCKED’s Puerto Rican community in Miami weighs as heavily on the protagonist, Adolfo (Germain Arroyo). She is, for much of the film, in the parlance of the trans community, an egg.

Presenting as a boy, Adolfo helps with her father and older brother’s landscaping business, but her time is primarily dominated by training to box and boxing. There is talk of distant, ephemeral goals like Golden Gloves and the Olympics, but for Adolfo, the most significant thing about boxing is how it allows her to more closely relate to her body. Beneath her bed at home is a cardboard box that on first glance is labeled “training,” but is actually covertly labeled “transition.” Despite never having said the words aloud, Adolfo is wrestling with being at odds with her own body. So by boxing, she can fund her transition and also receive physical punishment that dances an edge for her. On one hand, her body and face aren’t what she needs them to be — so the bruises and split lips feel validating — but it also makes her goal of being pretty and femme-presenting seem more distant.

Adolfo is a nesting doll of othered characteristics. Throughout the film, a B-plot boils about how Adolfo’s father and brother did a landscaping job for a customer who has now left a negative Google review and asked fellow cretins to do so as well. CLOCKED never loses sight of Florida’s rightward swing and makes sure to reinforce for viewers that even cities like Miami are creeping into the arms of open racism. Adolfo and her family are Hispanic, in a state where hate is now routinely rewarded. Adolfo and her family are Puerto Rican. Within Miami’s Hispanic community, the Puerto Rican community is dwarfed in size by the Cuban community, which is often celebrated as essential to Miami’s heritage, and thanks to the broad acceptance of conservative politics by the Cuban community, they often get a pass from Florida conservatives, where Puerto Ricans don’t. That said, Adolfo’s family is deeply conservative and religious. Multiple times in the film, we see her family’s revulsion towards the queer community. Lastly, because she hasn’t been able to give voice to her identity, she starts the film isolated, even from Miami’s queer scene. When she eventually does attend her first drag show, she’s a stranger in a strange land, afraid of mis-stepping and not knowing what to say.

She seems most at home in sequences by the sea, where she’s isolated, contemplating herself and her options. These moments play with some of my favorite themes in film, the push and pull between instinct and order and humanity’s relationship with the divine. Germain Arroyo is a fantastic performer, unafraid to lean into deep sincerity in their performance. When they twirl by the beach because they feel free in the moment, or explain their relationship with God, we believe them. They bring Adolfo to life in a way that feels fully realized.

Arroyo is best in the film when bouncing off of Armand Fields as Cleo Pockalipps. While Adolfo feels unable to share anything about her identity with her family, and only barely able to articulate the truth to Camila (Marisa Davila), a friend that helps run cover for Adolfo, with Cleo we see Adolfo come alive. She’s able to ask questions about the bigger world she’s stepping into and rise to the challenge of introspection demanded by Cleo. One of the best sequences in the film comes when Cleo repeatedly asks Adolfo to define herself. Since Arroyo never runs from sincerity in their performance, the resolution of the scene, which could have felt cloying and trite, instead feels we’ve been exposed to raw nerve.

The film couldn’t be carried on just a single performance and thankfully, Salzman doesn’t expect it to be. He’s populated his Miami with believable and real characters to populate the boxing scene, drag community, and Adolfo’s family. Performances feel real, and are drawing strength from a sharp and compelling script. Everything that tumbles out of the actors’ mouths has that every-day plausibility that can only be the alchemy of good writing and an environment where an actor is free to really find their character.

Salzman takes advantage of the natural grit of shooting digitally. Miami is a patchwork of discordant visuals. There’s blue fading into a steel tone of the film’s sea, endless and diffusing into the horizon. There’s the sickly taupe of walls as Adolfo and Cleo hang posters for a missing trans woman. There are the bursts of color the film associates with both boxing and drag. When Adolfo attends her first drag show, the scene is shot in such a way that the location almost has a church-like atmosphere, and the posters of Puerto Rican boxers on Adolfo’s bedroom wall read to the viewer as Catholic devotion to a Saint. This all makes sense within the context of the film, as one of the bigger ideas the movie wrestles with is how Adolfo reconciles their need to live their truth with regards to their gender identity and their Catholicism.

God is never far in CLOCKED. Whether it’s how the right feels emboldened in Florida, Adolfo’s family’s Catholicism creating a wedge making it harder for her to come out, drag queens praying to an amorphous, undefined divine before going on, or Adolfo’s own religious journey, God is always there, just out of frame.

Just as with FRESH KILLS, the film expresses a universality to the experiences depicted, which some viewers should experience. Who hasn’t felt restless or alienated by their parents’ expectations? Who hasn’t lived in one community while longing for another? I urge you to get to know Adolfo. You might just find some of yourself.

Tags: Armand Fields, Barker Gerard, Bernard Salzmann, Brody Wellmaker, Byron Lopez, Clocked, Danell Leyva, Drama, Florida, Fresh Kills, Gene Paul Gayol, Germain Arroyo, Jennifer Esposito, LGBTQIA+, Marisa Davila, Miami, Noah Salzman, Puerto Rico, Rinska Carrasco, Victor Rivers

No Comments