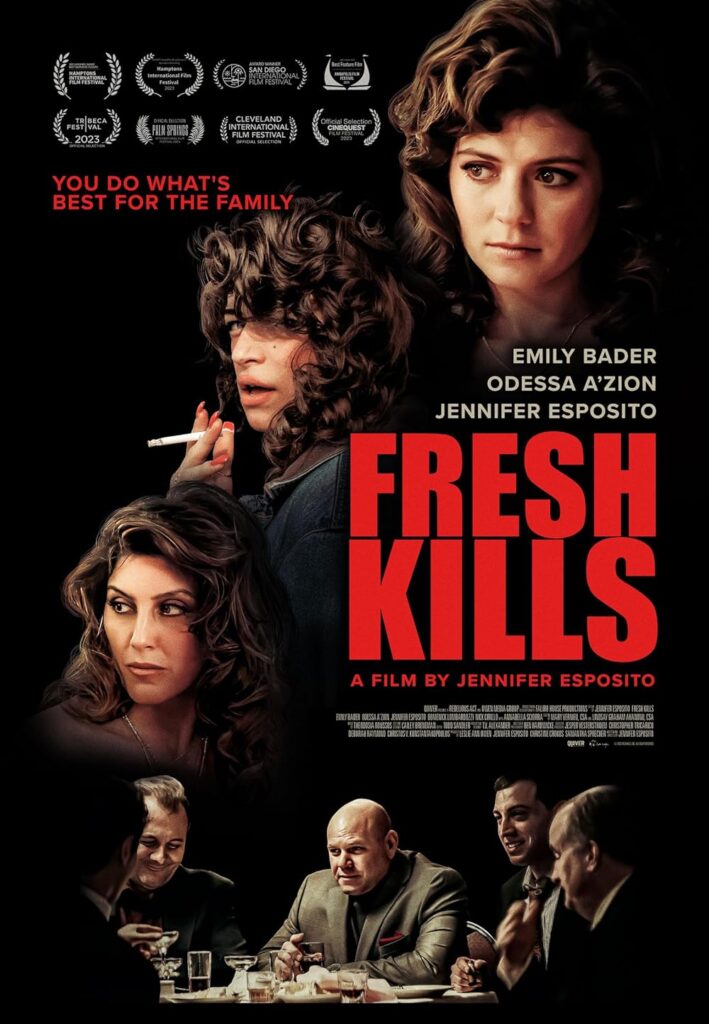

A woman records a video of herself walking down the zig-zagging hallway of the Harkins Shea 14 in Scottsdale, Arizona. As she passes each successive theater, she’s met with posters and advertising collateral for major studio pictures. There’s a giant standee for Inside Out 2. Here’s a massive poster for Despicable Me 4 hanging from the ceiling. Each respective theater is adorned immediately outside its door with a standard 28”x40” poster for the film playing inside the theater, until she gets to the theater at the end of the hall, the smallest auditorium in the place. Outside that theater is a poster for gift cards for popcorn. Yeah, popcorn. There’s absolutely no way anyone would know that one of the year’s best films, FRESH KILLS, is playing in the auditorium. It’s clear from the video that frustration with the lack of marketing and awareness for the film is percolating.

The following week, FRESH KILLS launched on VOD in the US. In the best of worlds, a VOD launch can help give a great film new legs. Launching both the Apple and Amazon VOD stores, one sees no placement whatsoever on the splash pages for FRESH KILLS. Noticeably, on both storefronts is a row labeled “Sponsored New Releases.” This essentially creates a user feedback loop for curation. Studios pay for placement into the sponsored space, meaning casual browsers only see what’s been paid to be placed. What do they search for later? What they’ve seen on the store. The films with sponsored placement.

Meanwhile, we’ve been in a space where film media has spent much of the last few months lionizing Francis Ford Coppola for self-financing his long-held dream project MEGALOPOLIS and Kevin Costner for doing the same with HORIZON: AN AMERICAN SAGA. I don’t mean to denigrate either artist. Francis Ford Coppola is literally one of the best to ever do it, and any serious conversation about the greatest films of all time will include THE GODFATHER, THE GODFATHER PART II, and APOCALYPSE NOW. Kevin Costner’s artistic vision is more closely tied to the mythic American West than any other filmmaker, and for his understanding of how America’s colonial westward expansion reflects the human experience, he won Best Picture and Best Director for DANCES WITH WOLVES. Of course, we should be excited about them getting to finally make their dream projects.

What I’m talking about right now is the way we’ve fetishized the financial risk they’ve undertaken. Francis Ford Coppola personally has a net worth of $400 million. In addition to that, he owns American Zoetrope, his film production company, a number of wineries, restaurants, resorts, a live entertainment venue in the Napa Valley, a lifestyle brand focused on his endorsement of products and — no shit — a cannabis brand. When Coppola announced that he would self-finance MEGALOPOLIS’s $120 million budget, he did so by selling some of his winery holdings — not even all of them. The ones he did sell are also branded Coppola Winery, so even though he will no longer own them, they still represent revenue through his lifestyle endorsement company.

Kevin Costner’s net worth also sits at $400 million and he has seen an increase in his asking price as an actor in recent years due to the TV series Yellowstone. His salary in Season One was 500,000 per episode and by Season Five, it had reached $1.3M per episode with a similar scale increase in his other work. Costner’s fortunes are not confined to his acting income. He’s a majority owner in Ocean Therapy Solutions, a firm with patented technology for separating oil from water in the event of spillage. After the Deepwater Horizon spill, Costner’s investment in the company took off when BP ordered 32 of their units for other oil rigs. He owned a casino for 20 years and owns a $5 million dollar attraction in Tatanka: The Story of the Bison. The museum/roadside attraction functions as a place where tourists can learn about the bison. Costner assumed part of HORIZON: AN AMERICAN SAGA’s cost to the tune of $38 million but found two anonymous investors to assume the rest of the risk.

These films should be exciting to us because they’re long-time passion projects by special filmmakers, but fetishizing their personal risk rings hollow because, well, the risk to them individually is minimal. These men own wineries and oil separation businesses. There is no risk of financial ruin to either of them because of these projects. If film media wants to call attention to legitimate risk as the cost of making a movie, Jennifer Esposito mortgaged her own home to make FRESH KILLS.

The media reaction and public reaction to FRESH KILLS has sadly hovered between disinterest and misogyny. The film has no meaningful marketing budget from distributor Quiver, and Esposito’s efforts to garner attention for the film have met with frustrating results. One talk show appearance to promote the film was met with Esposito mainly fielding questions about her personal life until the waning seconds of the segment. Reply guys on Twitter pepper her with questions about why Domenick Lombardozzi isn’t more prominent in the marketing. Selling FRESH KILLS has been fresh hell.

That’s a shame, because FRESH KILLS is a special film. Like Costner’s DANCES WITH WOLVES, this is also a debut directorial effort, and the film burns with a naked intensity rarely seen. Esposito has said she has wanted to make this film for sixteen years, and it is evident that personal truth is contained in every frame. On a surface level, someone might say the film is simply a recontextualized mob story rooted in the female perspective. I find that read reductive, because at its core what FRESH KILLS is really about is how toxic parents can wound their children deeply, and how families choose to uphold systems of abuse. There is a repeated motif in the film of a charming-but-abusive patriarch pretending to fly an imaginary airplane, and the whole thing rests on him prying out of his family an admission that they trust him. It feels so familiar, so real. You get the sense that Esposito has experienced this very ritual, or a variation of it in her life. The pain runs so deep in these scenes that on my first viewing, I had to look away.

FRESH KILLS is ambitious. It follows the Larusso family through four different non-sequential years, starting in 1987. The crux of the film is the relationship Rose (Emily Bader) has with her older sister Connie (Odessa A’zion). Like so many sibling relationships, Rose and Connie’s relationship changes shape over the years. When we meet them as young girls in 1987, we see that Rose and Connie are playing a variation of Dad’s (Domenick Lombardozzi) plane game, with Connie holding Rose aloft while Rose stretches her arms. The trust between these sisters is freely given, and the trust held by their father is demanded.

Immediately after this comes a moment when the young girls are hiding in their father’s car in the garage, planning on surprising him, and wide-eyed, they hear and see him conduct mob business and see a pistol tucked in his waistband. This scene is less about the mob, but more about those stark moments of clarity when a child first realizes who their parent is. Every child experiences something like this, whether its a moment where they see a parent dodge a phone call about a bill, drink too much, or yell at a service worker, just to feel powerful. A lot of FRESH KILLS is about the unspoken agreement between parents and children to carry on after kids are burdened with the horror of knowing who their parents are.

For Rose, this becomes too much. Despite living in the greater New York metro area on Staten Island, her world feels unbearably small. Women are expected to marry within the small coterie of age-appropriate men within the crime family and then swallow any dreams they may have had. Their job is to maintain the sheen of an unwounded home, despite the day-to-day cost of the men’s participation in crime. An early scene has young Rose and Connie peering from the top of stairs down at an argument between mother and father during a rare moment where their mother, Francine (Jennifer Esposito), breaks ranks. Their father looks up and tells the girls to “Go back to sleep, girls, everything’s fine,” and their mother replies “No, everything is not fine.” The power in this moment, like so much of the film, is the universality of it. Anyone who has ever been a child in a house where the parents have a broken marriage but refuse to separate will see themselves perched on that landing, looking down at the arguing Larusso parents.

Everything is not fine.

The moment at the top of the stairs calls to mind something true throughout the film. The camera movement is understated and never calls attention to itself. When the camera does move, it’s in slow pushes, pulls, and dollys. It’s like the camera is as nervous and uncomfortable around this family as Rose is. The film is often more interested in precision cuts that underline its themes. The film opens with a shot of a red sports car sliding into place along the waterfront, facing Manhattan. Close enough to see, but an eternity away. The red sports car, forever cinema’s avatar for unattainable dreams. The camera cuts to the interior of the car, and we see in quick succession a rosary hanging from the rear-view mirror, a pistol, a stuffed animal, and a blood covered hand. Violence, control systems, and scarred childhood are immediately introduced visually as themes. Just because FRESH KILLS’ camera doesn’t bring attention to itself doesn’t mean it doesn’t have a lot to say.

Peppered throughout the film is an intriguing subversion of The Sopranos‘ recurring motif of Tony watching television. Mob-themed media is frequently in conversation with its genre contemporaries as they often are dealing with themes related to family, the second- and third- generation immigrant family experience, control systems, and the fallacy of the American Dream. In The Sopranos, Tony is frequently depicted first in the living room and then in the pool house watching television. It’s never new film or television that Tony is watching: It’s always classic cinema. His escape is nostalgia. Nostalgia as escape is a primary theme of Martin Scorsese’s GOODFELLAS. In FRESH KILLS, Rose is often seen watching daytime talk shows. Her escape is the tawdry spectacle of Phil Donahue and Sally Jesse Raphael. It’s difficult to overstate the cultural prominence of the daytime talk show in the ’80s and ’90s. A generation of Americans tuned into these shows every day to affirm to themselves, “At least my problems aren’t as bad as the poor bastards on Donahue.” Each one of these hosts had a different way of communicating their superiority and separation from the topics they covered. So naturally, Rose finds escapism in these shows. She wants to be separate from spectacle and able to sit in judgment of it. She dreams of going to Manhattan and becoming a daytime host, getting away from her father and the family that protects him.

Rose’s sister Connie finds different ways of dealing with suffocating the pain of being in the Larusso family. Odessa D’Azion spends much of the film with bags under her eyes and smoking. Exhaustion, anger, and dependence are her symptoms for being in this family. Unlike Rose, she shows more outward compliance toward the family’s rules but is quicker to anger and quicker to lean on the illusory escapes of a single night.

One story point that ultimately turns tragic is when Rose and Connie’s father buys them a bakery with the hard-to-believe explanation that it’s something they can do together, as a family. They’re excited until they realize that it was to create one more mechanism of control, and to have yet another place to do mob business. Even gifts… especially gifts, are just another tool to enforce silence and compliance.

Equally as impressive in front of the camera is Jennifer Esposito, as mother and essentially as minister of propaganda. She stamps out Rose’s desires for expression or liberty and recasts all of Rose’s attempts to develop her own identity as a gross betrayal. There’s a moment, later in the film, when she finds out about a betrayal by her mother and father which is indisputable, and Esposito icily sells it as a loyalty test that Rose failed. There’s so much poignance and sadness in Esposito’s performance as well. Rippling beneath the surface is awareness that she knows every time she enforces loyalty, it is hurtful to the girls and she is, in practice, full of shit. In the first act there’s a great moment between Esposito’s character and young daughter Rose, who hasn’t yet started to show signs of rebellion but is starting to show awareness of what her father does. When dropping the girls off at school, she turns to Rose and says, “Wanna get an Egg McMuffin?” and then she takes Rose home and tells her a romanticized story about a time a fashion photographer expressed interest in shooting her. As the film unfolds, we realize that this photographer story is her daytime talk show. It’s her looking back with nostalgia at the last moment she considered escape and rebellion.

Esposito has said that she’s wanted to make this film for sixteen years and it shows. Every frame, every line of dialogue, the fragile structure of this broken family, all thoughtfully considered. Like MEGALOPOLIS or HORIZON: AN AMERICAN SAGA, this is a dream project. Esposito has torn her heart out and showed it to us. It would be a shame if people missed it because Variety didn’t fawn over its self-financed budget. This is something special, and a uniquely perfect portrait of a wounded and broken family.

Find out where you can see FRESH KILLS at the film’s official website.

Tags: Annabella Sciorra, Ben Hardwicke, Crime, Domenick Lombardozzi, Emily Bader, Jennifer Esposito, New York City, Nick Cirillo, Odessa A'zion, Quiver Distribution, Staten Island, Stelio Savante, The 1980s, Theodosia Roussos, Todd Sandler, Tribeca Film Festival

No Comments