“I am afraid there is only one person in the world who could make a good film about my prints; me.”

The first opening image of moving across a woman’s leg seems to take much longer than it actually should, increasing the sensation of ‘infinity.’ The sound we hear also puts us in a different place and surprises us as the buzzing of a tattoo fun. Escher is already well entrenched in pop culture, and outsider culture. Escher is such a malleable figure, as he wasn’t working for the sake of being an artist. The film, to make Escher the filmmaker, uses his own letters and notes to comprise the narration for the film, evinced by Stephen Fry. A fan letter from a mathematician praising his work confounds Escher, yet his mathematical experimentation seems to make him a man of fractions and fractals.

The film travels through time rather than focusing on a direct chronology. Learning about the hippies and their interest in his work also baffles the man, witnessing placemats colorfully splashing his black and white prints, without no permission granted. This infuriates him, but he obviously learned to enjoy the praise. Graham Nash of Crosby, Stills, Nash, and Young relates his own first introduction to Escher when Eric Burdon of The Animals shows up at his flat with an Escher book, and viewing the book changed his life. He calls Escher and tells him he’s a brilliant artist, and Escher’s reply was “I am not an artist.” Mr Nash asked, If you are not an artist, what are you? Escher’s reply, “I am a mathematician.”

He did go ahead and enroll at the Harlem School of Architecture and Decorative Arts to study architecture, though his focus shifted and he began more entrenched in the decorative arts. The filmmakers chose to match up sections of diaries and with drawings, and events Escher attended. We’ll most likely not have the opportunity to hear others read Escher’s texts as Escher, though Fry adds so much emotion to Escher’s words it’s hard to think of his glowing worldly observations as a ‘mathematician.’ The filmmakers’ choice of texts to offer, Fry’s emotive read, and the animations and images the filmmakers conjure, all combine to give us maybe the fullest exploration of this artist, who in image alone comes across as almost mechanical, though here he is a man in love with life and the world. There is too much ‘artist’ here to deny him that title. M.C. Escher was a man who very much loved his environment, and the world around him.

These investigations into the natural world expose much more of Escher than we can know from his more famous pieces. When he finds flowers in a field he puts his face right up to the plants, falling into their beauty, and discussing their components of shape and color. Fry’s vocalizations continually give rise to Escher’s words, though keep the man contained to his own expressions. And these noticings of life around him become more and more poetic; “the loneliness becomes unbearable” is not usually a phrase we ascribe to artists, often thinking of them as locked up of their own accord.

Here art scholars are not just making a film about an artist, but want to represent that artist to the point that he can be present in the film itself. When Escher travels to Alhambra, Spain, Lutz shows buildings you would expect to find in an Escher drawing, and in sketch form they eventually become the bricks of Escher’s future constructions. It is in Alhambra that Escher first begins to explore his inner designs as his mind becomes fascinated with the repetitions in the Alhambran tilework. The filmmakers then find Escher’s texts ecstatic at this find, and correspondingly show us Escher’s designs of living creatures in the place of geometric objects.

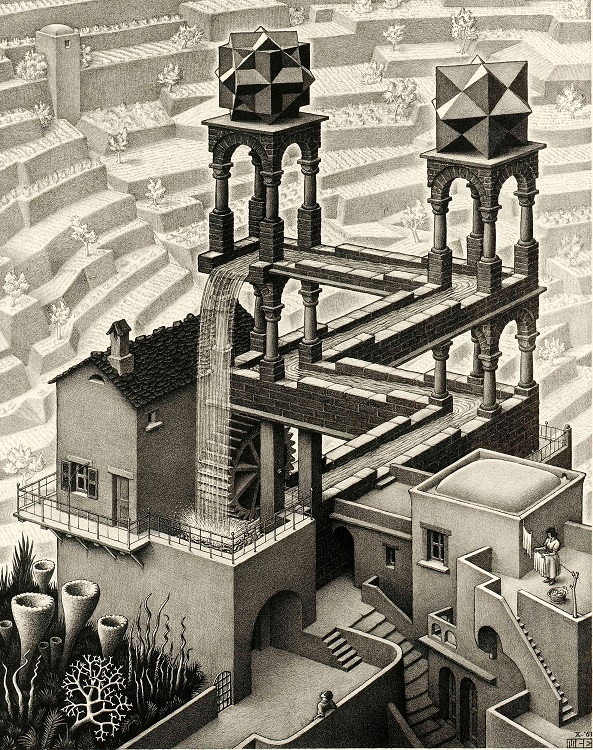

Once he left Italy, at age 40, he realizes a formation of inner images, that he has things of his own creation that had to be birthed from his mind. “That I could express something others don’t have. I am 40, the age at which most people are at their best. For me, this is the richest of times.” This is the period where we begin to see birds and fish in his tessellation motifs and his geologist brother, who noted that he was ‘unknowingly applying a kind of two-dimensional crystallography.’ Escher found the discussions of science too dry, though he discovered ‘expressing endlessness within a limited plane.’

Central to the film are Escher’s musings on the mathematical qualities of his work, and his interest in perhaps creating an animated film as a work, though feeling people would be quite bored with it!

Delving further into Escher’s work and creations, filmmakers Robin Lutz and Marijnke de Jong offered some time to further explore their presentation of Escher’s constructions.

DAILY GRINDHOUSE:

When did you become interested in this project and how did you gain access to this material and choose this narrative direction?

MARIJNKE DE JONG:

We went to the family of the Escher Foundation because they have all rights and they have a large archive, though there are also documents in the public domain. We were busy for a full year putting everything together that we could find, especially the private documents, because they are the most interesting to us. He had ideas, for example, about the metamorphoses. He wrote that if he had been capable, he would have made an animation of it himself. So through the film we could let him talk. And in his private documents, he’s really writing down what he is feeling and thinking. And in his own articles and lectures, they are mostly a bit boring because he’s trying to explain mathematically what he’s doing. But he was not a mathematician. He called himself a mathematician only because he didn’t feel very comfortable being called an artist.

DAILY GRINDHOUSE:

If you had to define him in some way, could you do so or was he so vague about what he was doing that it’s difficult to call him either a mathematician or an artist?

MARIJNKE DE JONG:

You can definitely call him an artist and not a mathematician because he complained constantly that he did not understand what mathematicians are. He was creating his work by instinct, but he didn’t feel very comfortable being called an artist. He was going for his own images and he was really driven to put them on paper and they never came out as he wanted.

ROBIN LUTZ:

Several years ago two professors in mathematics were viewing a print exhibition. They felt it was mathematically so complex that they started to recalculate mathematically what Escher was doing fifty years earlier. And they proved it was completely scientifically correct, but Escher didn’t understand anything about mathematics. He created his work by instinct. It’s really just wonderful, he did it by instinct and fifty years later, scientifically approved by two university professors that what he was doing was scientifically correct. That’s amazing.

DAILY GRINDHOUSE:

There’s something so precise about his images, and the way that he would make an entire flock of birds and school of fish transform insideeach others spaces, or bats and angels fit inside of a circle, and it never felt forced, the works feel very natural. They ‘fit.’ There is definitely a sense of space and how things fit together. When he saw the repetitive Eastern middle eastern motifs, that’s when he really began to flower.

How did you work out how you would represent his work through animation? Because the brain attempts to figure out what it’s seeing. And somehow he was able to come up with this picture and create this environment and have it exist in a world that makes it difficult for your casual human to even process. I wonder with all the papers you had access to, did you ever read difficulties he was having, even with his own pieces, in attempting to finalize these environments that can’t possibly be, but seem so exact as he creates these infinitive worlds.

MARIJNKE DE JONG:

He worked for months on these designs and he was making designs beforehand endlessly. And he had whole booklets with the systems and he had to figure out quite a lot.

ROBIN LUTZ:

Sometimes it drove him completely mad because he was seeing things in his mind that he couldn’t bring out into the two-dimensional form. Every piece of art from him took him an awful lot of time because he wasn’t a mathematician, but he saw things in a mathematical way, and had to figure out how to realize these images. And most of the time he was a little bit disappointed about himself because he saw things with more beautiful insight and much more complete than he could realize.

DAILY GRINDHOUSE:

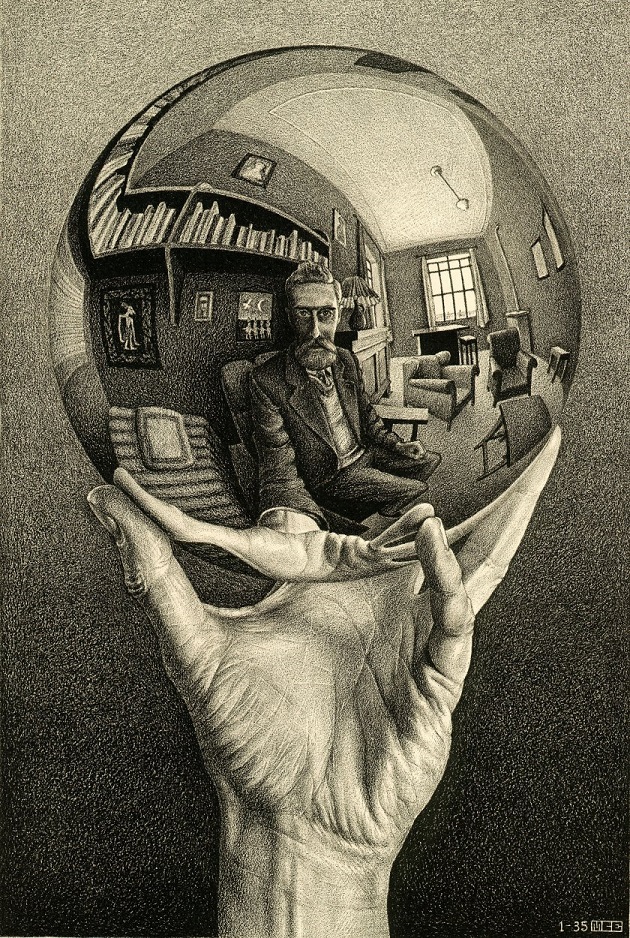

Did he ever use any tools too, like mirrors or mathematical tools, to try to realize some of his imagery?

ROBIN LUTZ:

As far as we know, he didn’t use any tricks or tools, he was just trying to get the images out of his mind.

DAILY GRINDHOUSE:

You definitely tap into the world of psychedelia and the interest that the hippies had in his artwork. I remember once in the ‘eighties, there was a sheet of blotter acid gong around of the two faces looking at each other connected with one ribbon.

But he never saw what he did in that way.

MARIJNKE DE JONG:

The main idea he wanted to express was infinity. With the staircase, there is no end. In other prints there is a constant repetition of action. He was a bit amazed at mathematicians who saw a visualization of their ideas in his work. I think the main difference with pop art is that he always used visual elements because he wanted normal people to be able to understand what he was doing. His problem in the end, was they didn’t understand what he was doing because he was creating abstract ideas.

DAILY GRINDHOUSE:

The last line of the film, shown on screen is “I can fill a second life with my work.” Was he interested in showing infinity in the world? Almost a cosmic sense of ‘forever’?

MARIJNKE DE JONG:

The infinity thing he already had also in his early works, for example, day and night, he is describing that day comes after night. And then again, days, and you have the sky that’s going to be around the Earth and the other way around. And there is a sense of infinity in his mind too, but not, I think in a very specific way.

DAILY GRINDHOUSE:

With the hippies being interested in psychedelic visions, they were obviously seeing much more than he was presenting in the work. It feels he wanted to show us more of the world than we usually know to see.

ROB:

But it’s also a way to look to the real world, but differently, but artists are going to look differently at the same world and they show it to you. For instance, his youngest son told us that he was walking in boots on these two big trips and he had a little magnifying glass in his pocket. He knelt down and looked to the little world that’s there for, for all of us, but we don’t see it. He saw it, through his magnifying glass as he was studying it. He showed the world.

DAILY GRINDHOUSE:

How did you choose Stephen Fry to be the man bringing Escher’s voice to life?

ROBIN LUTZ:

The director of the Escher Foundation had the idea for the narrator of the English version. Why not ask Stephen Fry? So we asked him and he said, “Oh, I am an Escher fan. Of course I’ll do it.”

MARIJNKE DE JONG:

We were looking for somebody who could really act because in the film, because we going from a young man to an older man. So it had to be somebody who, who can feel that and represent that in this voice as well. So you need somebody who is really an experienced actor.

DAILY GRINDHOUSE:

Did you hear any feedback from the sons for how their father was presented on screen?

ROBIN LUTZ:

We saw the feedback because we saw that the youngest son was crying. \ Crying. We saw tears, little tears dripping down. Very emotional.

DAILY GRINDHOUSE:

With all the material you had at your disposal, how long did you prepare before you even began this film? Like going through his notebooks, you know, and choosing what you’re going to have replicated in the film. How many months did you spend researching the material you had before you created the script that would be used to bring a shirt?

MARIJNKE DE JONG:

We spent over a year to get some idea about what he was writing. His emotions have been mostly unknown. It was constantly adapted for another year. And then in the meantime we had smaller pieces we had filmed. We spent over two years we spent refining it constantly.

ROBIN LUTZ:

It was more than one year for studying all the letters and diaries. And then we found the famous sentence about making a film about his work. So we had the form already, but you have to make choices. There’s much more to tell but you have to constantly make choices. It took us more than two years to, because although filming was done in in a few months, the preparing and the research, especially research, and also the international research, going to France, going to Italy because the youngest son lives in France. It took more than two years before we had a fuller plan.

MARIJNKE DE JONG:

As an art historian, I felt responsible for the fact that if you say that every word in the, in the film is really written or set by Escher, then you have to stick to it. You cannot invent sentences thinking he could or might have said it.

DAILY GRINDHOUSE:

Were there other people you were hoping to find that knew him or knew his art that would speak about him?

ROBIN LUTZ:

We needed his children, his sons, to be a witness of what Escher was telling us. And for the form of the movie, it was very nice to have somebody who was also a witness in the early sixties. And that was Graham Nash who wrote in his own autobiography three to three or four pages about his experience with Escher.

DAILY GRINDHOUSE:

Thank you for doing all this work. It’s really opened up my own understanding and appreciation for Escher’s work.

ROBIN LUTZ:

It’s very nice to hear that we, at least with you, fulfilled our purpose to let people look at Escher and to understand him better.

Click here for information on where you can see the film!

Tags: documentary, Eric Burdon, Graham Nash, Interviews, kino lorber, M.C Escher, Marijnke de Jong, Robin Lutz, Stephen Fry, The Netherlands

No Comments