When it comes to skateboarding, few can challenge the impact, notoriety, and widespread fame of Tony Hawk. Having served up countless, mind-melting tricks and stunts over his decades-spanning career, Hawk’s influence on the sport overall is unquestionable. Therefore, the surprise that he was becoming the sole subject of a new documentary wasn’t that it was happening, but more the fact that it took so long to happen.

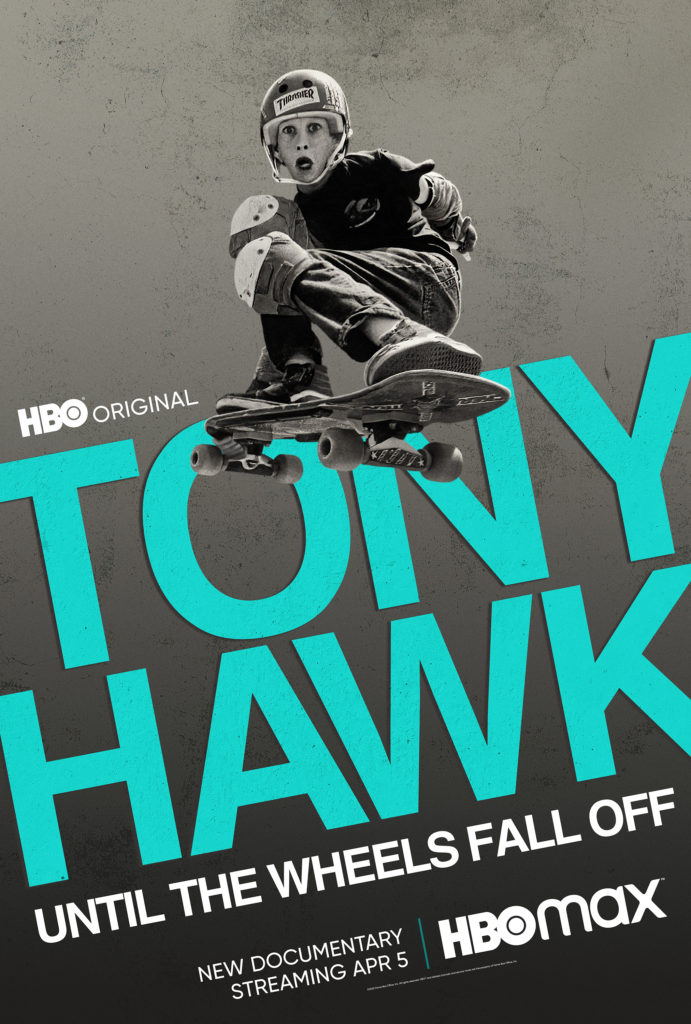

Directed by Sam Jones and produced by Mel Eslyn (HORSE GIRL) and the Duplass brothers (CREEP), TONY HAWK: UNTIL THE WHEELS FALL OFF is a personal look at the renowned skater. Charting his entire life (so far), the doc utilizes an engaging mix of vintage footage, and peer, family, and personal interviews to paint a comprehensive portrait of Hawk. While at times genuinely thrilling and inspiring, the doc also navigates some truly complex conversations about Hawk. Not only do those closest to him openly discuss Hawk’s compulsivity, but they also examine the very real physical repercussions of a life spent skateboarding — for Hawk and themselves.

Although TONY HAWK appropriately employs a bevy of killer songs to imbue the project with an authentic skate culture feel, the more intimate and personal moments required something different. For this, the creative team called upon the talents of composer Jeff Cardoni. With a beefy resume that includes projects like SILICON VALLEY, JUST FRIENDS, Netflix’s THE KOMINSKY METHOD, and Starz sports drama HEELS, Cardoni’s versatility and intuitive approach to subject matter made him a perfect choice.

For TONY HAWK, Cardoni countered the high-energy music of The Clash, Sex Pistols, Adolescents, T.S.O.L., and Devo with a delicate orchestral approach. Evolving and supporting Hawk’s personal journey from awkward teen to vert skater superstardom, Cardoni’s sensitive musical backdrop grounds the story with Hawk himself. Effectively stripping away the lights, crowds, fame, and sensationalized narrative, it is Cardoni’s reflexive score that shepherds viewers into Hawk’s life. It’s a bold sonic juxtaposition that on paper, wouldn’t seem to work, and yet somehow, it does. To dig into this interesting project a bit more, I sat down (virtually) with Cardoni for a revealing and lovely chat.

DG: I’m super excited to talk to you about this documentary today. While watching it I just kept thinking how wild it is that there hasn’t been something like this before about Tony Hawk.

Jeff Cardoni: I thought the same thing! [Laughs]

How did you become a part of this project?

I had worked with the editor, Greg Finton, before on a few docs. The last one we did was for Davis Guggenheim (HE NAMED ME MALALA) and Greg is like, the king of documentaries. He’s done a lot of really good ones (BILLIE EILISH: THE WORLD’S A LITTLE BLURRY, WHAT WE STARTED). So anyway, he had some of my music in the movie and recommended me. Then I got a meeting with [director] Sam Jones and we just kind of connected on some stuff.

The attractive thing to me was that a lot of the skating was covered by all of the source songs. They got so many amazing licensed songs. To me, the worst thing would be if the score had to handle all the skating and do a poor man’s version of what you would think skate music would be. So, I got to really focus on the kind of internal stuff and the emotions and, that’s what I like to do most. In a nutshell, that’s really why I was attracted to [this project].

What was your initial approach for the instrumentation and determining the tonal palette for the score?

It was an experiment for sure. Sam is pretty particular and he seemed to gravitate towards more acoustic-type sounds. And I, just by my nature, am more of an acoustic person than a synth guy. So, he’d always respond to hearing the squeaks on strings or the pedals on the piano. The things that made it sound real, you know? But I knew when I first had my interview with him and he said, “I used to be roommates with Jon Brion (ETERNAL SUNSHINE OF THE SPOTLESS MIND)” that he was going to be a tough one. Like, Sam knows music. [Laughs] So I knew it was going to be a challenge. And he’s very particular, but in a good way. He definitely pays attention to every little detail which challenges you. But it was fun!

You mentioned the killer source songs that are in this and, there are a lot of them. Did you work with the music supervisor at all? Or, at least know where the songs would be and what scenes would require your score?

We knew where [they would be]. But I mean, honestly, Sam and Greg were really particular about the songs they knew that they wanted to get and they were pretty much scripted. They kind of handpicked every song before the music supervisor was even on board. Greg, the editor is a skater and Sam is a skater. I think the whole reason and way Sam got involved was, in some of the old 80s videos, Sam is in the audience. He’s literally on camera. So that was his connection with Tony and they just knew all the songs.

I don’t know how they were able to do it and how they were able to get all those big songs. I guess because Tony is so iconic that some people just wanted to be associated, but I think they also got these sweetheart deals on everything. They got songs you normally wouldn’t be able to get on a movie which was cool!

As far as the juxtaposition goes, I was kind of worried. It could have totally gone into like a skate punk kind of thing for the whole documentary. Or, it could have been super introspective. But I feel like somehow, it worked. I read a couple of reviews where it said they complimented each other which, to me, was a relief. And for me, it was cool because, I think for people at a certain age, [Tony] kind of tracks your whole life. I can see where I was in my life the whole time, seeing his career rise and everything. It was cool.

It’s so true. I wasn’t super into skateboarding as a teenager or anything, but I vividly remember him doing the 900 and what an event that was. That moment transcended skate culture and became something else entirely.

Yeah! I think it was his brother, but they said something that really struck me. They said, “This wouldn’t exist in another sport.” Because, in another sport, you only get one try. You don’t keep going and going and going, you know? It was really cool to hear how that wouldn’t have happened. If it were football, you would have dropped the pass and it would be over. You wouldn’t get five more chances to keep doing it. I mean, it was amazing. I think everyone watching it knew it was going to happen, but it was still dramatic when he got it.

This doc is really a comprehensive look at Tony Hawk and covers his entire life (so far). Did you find your composing process mirroring his journey at all? Did you start at the beginning? Or, work backward and deconstruct a bit?

By the end, it’s a full orchestra on the last cue where, in the beginning, it started with just piano and solo violin. I just kept adding layers and layers to it as it got bigger. But honestly, the thing that kind of changed it all was, I was just screwing around at the piano and there was a cue that was a throwaway, but then they ended up really liking it. And, they put it under Rodney [Mullen] the first time he speaks. And, it really just stuck. I could sit there and listen to him recite the phonebook. He is just so cool. I’m like, “Just tell me about life.” [Laughs] He’s just so amazing, you know? And so, those two cues, the first time he spoke and then at the end when he says “Until the wheels fall off,” those are kind of the linchpins of the whole thing. They made it all fit together and, it was a happy accident.

To be honest, Rodney Mullen was my biggest surprise takeaway from this whole film. If he ever starts some sort of commune or health retreat, I will sign up so fast it’s not even funny.

[Laughs] I know! He’s just so cool. Oh man, it was so cool just hearing him talk. Yeah, wow.

What a treasure. You mentioned using an orchestra for this score. Can you tell us a little bit about that process, how you select an orchestra, and who you worked with on this?

Well, a lot of times it’s, unfortunately, dictated by budget, you know? In this case, it was, so we ended up doing it in Budapest. I think I had 45 players and then we did solo violin and solo cello here. A lot of times we record in Eastern Europe because it’s more affordable, but they’re great [musicians] too! They’ve got such a large classical music tradition. And, it’s always intimidating to me when you have them play stuff. They’re playing the classics all day, every day. Film music isn’t the most challenging sometimes, but sometimes it’s the simple things that are the hardest, you know? But they just make it sing. Some things, when you’re doing them in your studio you’re like, “Oh, this is so basic and simple.” But then when you have 50 people play it, it just really resonates.

That has to be a pretty cool experience hearing your music performed by a large group of talented people for the first time.

It’s awesome. It’s the greatest thing ever. The first time I ever did it, it was also the most intimidating thing ever. [Laughs] But it just always sounds better. It’s the humanity. Again, I like live players and I like acoustic instruments. For me, computer music is so perfect that it loses its emotion. For me, when I hear a Radiohead song or a Led Zeppelin and hear the squeaks on the guitar strings, it’s those imperfections that make me listen again. I feel like when music is so “in the box” and perfect, you miss those things. Subliminally, you miss them. You miss the humanity of it.

Let’s pull back a little bit and look at your overall composing career. From what I understand, you initially came to Los Angeles to pursue the rock star thing. How did the transition into film scoring happen for you? What attracted you to the field of composing for film and television?

It was a couple of things. I wanted to be a rock guitar player. I spent my twenties driving around and then when I got here, I got hired to be in a band that was signed as a lead guitar player. And, it was horrible for me. If you’re not writing the music, you’re kind of like a trained monkey. I just found that incredibly unfulfilling.

At the same time, I had a manager from my old band who was a music supervisor. He opened my eyes to this whole other avenue that I never really knew existed. So, I just decided to try and give that a whirl. I was pushing 30 and I was like, “Do I really want to drive around in a van trying to chase this thing?”

I was always kind of the mad scientist in the band and so, it just really opened my eyes. It was like a second act that actually, is more me than the first act in a lot of ways. So, I signed up at UCLA for some classes; orchestration and such. Then I just got a couple of assistantships for some people. And, it took a while. It took like, four years to kind of get something going. But, it was just a pivot. I didn’t really have any grand aspirations. It just seemed like all I ever really wanted to do was sit in the studio and make music all day.

I always say, failing at rock was the best thing that ever happened to me. It’s interesting because, back then, it wasn’t cool to be a guy from a band trying to be a composer. It was looked down upon. I literally did not put a guitar on anything for like, five years because I thought that would diminish my being a “real” composer or whatever. And now it’s like, “I lost to the guy from The Lumineers?” [Laughs] Or whoever. They’re all doing it. It’s tough. But hey, whatever.

I mean, you were just ahead of the curve, right?

Well, I mean, I didn’t have any fame to speak of. I wasn’t Danny Elfman coming from Oingo Boingo or something, you know? But, there are certain things I think you get from being in a band. You get kind of resourceful and you get…it’s not desperation, but it’s like a scrappiness. Constantly trying to get to the next thing, that kind of prepares you for what this is.

TONY HAWK is obviously a documentary and, this isn’t your first documentary. From a composing perspective, how is working on a documentary unique or different? Is there anything special about working with this kind of material versus a more traditional narrative project?

The thing I like about it is, I think you can think about the music as pure music. As opposed to staring at a picture and trying to write music that’s trying to do things to picture so much. It’s more about the emotions and what people are feeling. Especially in TONY HAWK. It was never really about what was going on with the picture.

Sometimes when you’re writing dramatically to picture, you’re focused so much on serving the picture. Especially in comedy. People attach so much to what they’re hearing to what they’re seeing. And I think you’re missing out on when music is playing something you’re not seeing and playing what someone is thinking, or what someone somewhere else is doing. Then I feel like, one plus one can equal three. It can add another layer of complexity.

I like it in that way. And, Sam was super interested in melody. All the pieces that were in the film were started on piano and were listenable pieces of music before they were put against picture. Which is good! Because, if the picture is driving it, the music can sometimes be super basic where you’d never want to listen to it. It can be just a tonal kind of thing which, in some pictures, works great. But as listening, that’s just boring as hell. On a documentary, I feel like you can’t get away with that stuff. It has to be music first and then they put it against picture. It’s fun in that way.

Another interesting aspect of your career that I have to ask you about is your television work. You haven’t just worked in TV, you’ve scored 30, 50, and 70+ episodes of TV.

Yeah, CSI: Miami was like nine seasons! That was like, 180 episodes or something! [Laughs]

That’s bananas. What are some of the perks of working on such a long-running project? And, what are some of the challenges?

I mean, the pros are, you have a job. [Laughs] And, there’s something about when you have a sound set up. You’re then thinking more about music than the sound and its kind of freeing. The hardest thing sometimes when you’re starting something is, “What’s it gonna sound like? What’s the palette?” That’s the hardest part. So when you have that solved, then you can think about the emotions, the action, and things like that.

CSI: Miami would change so much because we were on the air for so long. So every year in the summer, a producer would see the latest movie or something and they’d be like, “Ok. Next season we’re going to be like…” [Laughs] We changed a lot. So, it wasn’t the same thing for that many years and that kept it kind of interesting. It didn’t feel like I was doing the same thing for the 10,000th time. That would get hard. But I still, even if I’m doing something for a long time, I still enjoy it.

A lot of people now have these teams and they have ghost writers and they don’t write any of their own music. They just get a show and then they get two young guys to do it for them, you know? I don’t do that. I literally have written every note of every show I’ve ever done. That’s just me. People think I’m crazy and they don’t understand why, but again, it goes back to my point — I didn’t get into this to make money. It’s a privilege to get paid to make music every day.

To me, that’s the perk. I don’t want to have someone else do what I have been trying to do. The joy for me is making the music. It’s not getting the paycheck, it’s making the music. And there’s a joy in finishing something. And you put it on iTunes and you have however many cues and you can listen to them. There’s an art to it and you did it all so you know how it all connects. I still get a thrill from that.

Ok. So you’ve worked on commercial projects. You’ve worked on feature films. You’ve worked on documentaries and TV. I even heard a rumor that you worked on MTV’s PIMP MY RIDE back in the day.

I wrote the theme song for that! [Laughs] Who knew?

Iconic.

That was a favor to a friend. I was desperate at that point. If I told you what I got paid on that…[Laughs] I think I got like $500 bucks or something. That was, yeah. It was a thing. That was fun.

Do you think working on all sides of the industry made you a better composer? If so, how?

Oh, I mean, as a composer, as a musician, there’s no doubt it’s made me better. You’re just always changing. Creatively, it’s really cool to do different things. Sometimes it’s good to be pigeonholed because then people know what to do with you. Or in my case, I’ve done so many different things that someone could always go, “Oh, he did that so he’s not for this.” It’s a double-edged sword.

It’s not like I made these choices consciously though. You don’t know what’s going to come your way. It’s not like I have a crystal ball and know if I say no to this that this other thing is around the corner. Sometimes I look back and I say well, I never wanted to do comedy. It was never on the radar. My first big show was an action show so, how I ended up doing comedy sometimes, I don’t know. It wasn’t a conscious choice, but if I said no to some of them, I don’t know if I’d be better off now. I don’t know. Surely, it’s opened a lot of doors.

Someone said once, “You can only steer the ship a little bit. You can’t really change course.” You’ve got to just kind of ride the wave. If my first thing out of the gate was some Sundance film and I hooked up with this director who became the next trendy whoever, then it might be different. But I for whatever reason, haven’t had that. So I keep going.

You never know who you’re going to meet on what and what is going to turn into what. I mean, I always wanted to do films, but I’m glad I did TV, you know? I think I’m on my 54th film right now, but everyone thinks, “You’ve just done a lot of TV.” No one knows about it. But I don’t care. I like them all. I’m glad to be working. And especially with everything going on in the world, I’m just happy that the phone rings for something. At a certain point, we all kind of age out and people want the hot new thing. So I’m going to fight my hardest for that not to happen to me.

I feel like because I’ve done so many things, I’m a way better composer now than I was when I started. And way more versatile. I think that only helps you. I mean, we’re all musicians at the end of the day, you know? I also think being a musician is a lifelong pursuit. It’s not like you learn it and then you have it. You learn something new every day or you try something new. If I get on some film that is some genre I’m not that good at, then it becomes fun. It’s a challenge and it keeps it interesting.

TONY HAWK: UNTIL THE WHEELS FALL OFF is currently available on HBO Max. You can also learn more about Cardoni and his impressive musical career by checking out his website, here.

Tags: Adolescents, Devo, Interviews, Jeff Cardoni, Mel Eslyn, music, Sam Jones, Sex Pistols, T.S.O.L., The Clash, Tony Hawk

No Comments