It seems like most of my life… well, from 1971 on, anyway… I had heard a lot about Ken Russell’s THE DEVILS, and yet I had heard very little about it. The major impression I got – probably due to my father’s Playboy magazines – was “Lotsa naked nuns!” (with an understood undercurrent of “Hurr hurr!“) I knew it was based on historic fact, and largely on Aldous Huxley’s book The Devils of Loudon. Past that, I didn’t know very much, because it was almost impossible to see, hidden away by Warner Brothers as something to be ashamed of, or – more to the point – to be feared.

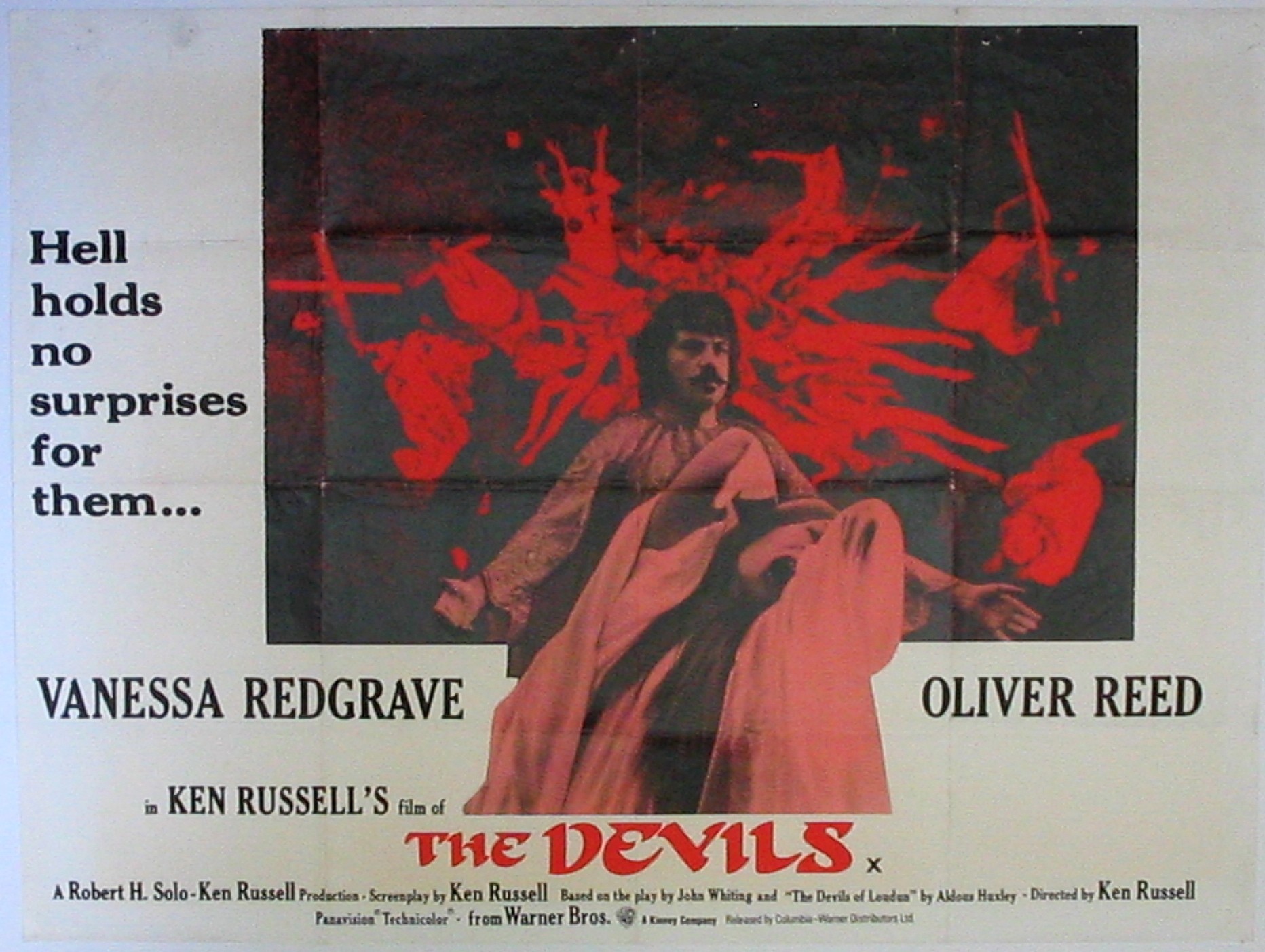

There were a couple of VHS releases over the years, of a reportedly heavily cut “R” version. An occasional festival showing was grudgingly agreed to. Finally, this year, the British Film Institute released a DVD of the “X” Certificate version which originally ran in England (to great controversy) in ’71. Still not a bona fide Director’s Cut – which we may never see – but probably the best we can hope for. Warners denied the BFI permission to press a Blu-Ray, even.

So finally, now, thanks to my region-free DVD player, I can watch this movie. And I found out how “lotsa naked nuns” can be reconciled with “genuine masterpiece”, because holy cow you guys is this movie ever good.

Oliver Reed plays Urban Grandier, a Catholic priest in the fortified French city of Loudon, circa 1634. Loudon is an anomaly in that time period, a place where Catholics and Protestants live and work together in peace. After the death of Loudon’s governor, a workforce arrives to tear down the city walls by order of Cardinal Richelieu, as self-governing, self-contained cities stand in the way of his consolidation of power over Southern France. Also standing in his way is Grandier, who has papers naming him the city’s governor. Lacking a royal decree to tear down the walls, the force must retreat, much to the ire of the Cardinal.

Grandier has been planting the seeds of his own defeat for years, however; he is not a very devout clergyman, and has, in fact, gotten the daughter of a local wealthy merchant pregnant, among other things. Concurrent with his assumption of the role of governor and protector, though, he finds and returns the love of a good woman, even marrying her illegally in a midnight ceremony. In Grandier’s own words, he finds “the Grace of God in a woman,” and this, while working to protect the city he loves, leads him to a higher plane of spirituality… although perhaps too late for him.

For in Loudon’s Ursuline nunnery is Sister Jeanne, a hunchbacked Mother Superior who, like many women in the city, is madly in love from a distance with Grandier, and becomes obsessed with strange, blasphemous sexual fantasies about him. Once she finds out about the secret marriage – a very poorly kept secret – her frustration decays instantly into bitterness, and she makes accusations that Grandier is a sorcerer, an incubus who visits the nunnery at night and has his way with the nuns.

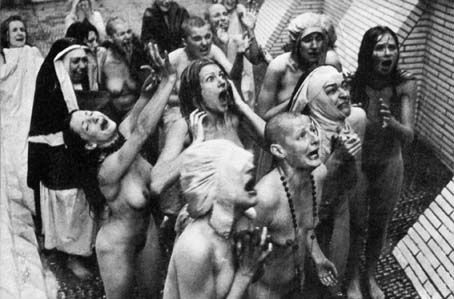

At first, these accusations are seen as exactly what they are, the fantasies of a frustrated, hysterical nun, but Jeanne makes her accusations more elaborate and bizarre, goaded on by the nobleman charged with bringing Loudon down and the Church’s own Witchfinder General. The other nuns, threatened with execution, basically turn state’s evidence and take part in what becomes a sensational freak show, attended by the bourgeosie and noblemen; three exorcisms a day, with the nuns giving it their all like an improv troupe from Hell. This is where you fulfill all your naked nun picture needs for Playboy and the like.

Grandier returns from a trip to the Palais Royale to secure the future of Loudon only to find the deck stacked against him. Arrested, tortured and condemned to burn at the stake, Grandier exhorts the assembled crowd – which has turned against him as only mobs can – to fight for their city. As he breathes his last, explosive charges bring down the walls of Loudon, completing Richelieu’s victory.

I knew that Ken Russell had described THE DEVILS as “my only political film”, but I was unprepared for just how political it was; the movie is a nightmare about religion turned into a political tool, and I can think of few things more absolutely relevant to the world today than that central concern. Warner can hide behind the supposition that blasphemy is the reason for their reluctance to make THE DEVILS more generally available, but it’s the politics that truly make this a dangerous movie. In a country where people refuse to see Hugo because Scorcese also made The Last Temptation of Christ twenty-five years ago, there would be theaters set afire for showing this movie.

But even the blasphemy charge becomes shaky when one makes the slightest attempt to do any research (which the beautiful 2 disc DVD from the BFI supports). The most infamous scene, which has come to be known as “The Rape of Christ”, which was excised before the movie even premiered, is defended by no less than the theologian Rev. Gene Phillips, SJ, for years a consultant to the Catholic League of Decency, who regards the movie as a depiction of blasphemy, and not actual blasphemy.

The excised scene occurs after one of my favorite scenes, where a nobleman (actually the King in disguise) is brought in to one of the exorcisms on a palanquin; after watching, amused, for several minutes, he offers the Witchfinder a small ornate box from the personal collection of the King, containing a phial of the Blood of Christ. The Witchfinder thrusts it at the assembled mass of naked, cavorting women, and they all fall, writhing, then proclaim themselves gratefully cured. The masked nobleman then opens the box, revealing that it is empty. “What trick have you played on us?” cries the Witchfinder. “What trick have you played on us?” asks the nobleman. He then turns to the nearest naked nun and says cheerfully, “Have fun!” before being carried away on his golden litter.

After this comes the censored segment, where the women go completely over the top, pulling down a lifesized crucifix and ravishing the icon of Christ. This is unquestionably the climax of Russell’s exorcism setpieces, and … this is very important… is intercut with scenes of Grandier on the road back to Loudon, stopping to have a simple Communion in some particularly breath-taking scenery, simply feeling the presence of God in his surroundings and his simple tools of faith. The contrast between the increasing purity of Grandier’s personal faith and the utter corruption of religion taking place in Loudon Is what Rev. Phillips appreciates and endorses, and if an ordained Catholic priest can see past the naked nuns and ballyhoo to perceive what the director is after, the rest of the bloody world has no excuse.

But you’re not going to see that scene, except in snippets in the extras of the BFI disc. The actual footage was thought destroyed until only recently, and timorous Powers That Be still do not wish it to be on display. For many years there was a very real effort to make the R-rated cut of THE DEVILS the only cut.

The removal of that footage does little to reduce the impact of the movie, though Russell doubtless thought it had been hopelessly gutted. His point is still made in spades to anyone not going “Hurr hurr, nekkid nuns”. The movie is a symphony of intensity, and as Grandier is spared no pain after his arrest, neither are we, as he is subjected to torture to find his Witch’s Spot (a bit of tongue mutilation that the makers of Mark of the Devil must have seen and thought, “Ooh, we need to make a movie about that!“), a mock trial, shaving of his head and beard to humiliate him, then even more torture to wring the confession of witchcraft from him (not too explicit thankfully, but no less harrowing) and his subsequent burning at the stake.

The power flows from Russell’s first-rate, committed cast; Oliver Reed in possibly his best performance, Vanessa Redgrave walking a very delicate emotional tightrope as Sister Jeanne, obviously intelligent but trapped in a world and a body she despises. Marvelous supporting work from Dudley Sutton, Murray Melvin (who carved out a niche as the world’s finest portrayer of pinch-faced, cadaverously thin clergymen, see also BARRY LYNDON), and Gemma Jones as the woman who turns Grandier’s life around, but alas, too late.

In case I’ve not made it clear: THE DEVILS is a stunning movie with incredible production design (a young Derek Jarman!), marvelous acting, and a message as sadly eternal as it is necessary to be eternally said.

You might say I liked it. And it is a damned shame I had to jump through so many hoops – import DVD, special equipment – to simply watch such an important piece of – not even merely political- but cinema history.

DR. FREEX

- [THE BIG QUESTION] WHAT’S YOUR FAVORITE FEMALE ENSEMBLE IN MOVIES? - July 22, 2016

- [IN THEATERS NOW] THE BOY (2016) - January 24, 2016

- Cult Movie Mania Releases Lucio Fulci Limited Edition VHS Sets - January 5, 2016

No Comments