The summer heat hung as thick wool in the air. My mother’s muffled cries bounced like rubber down the hallway, the retro wood paneling quaking beneath her excruciating whimpers. The shade-less night light cast a searing glow, almost taunting me, as the darkness around it grew to a suffocating temperature. I yanked the lion-stitched comforter over my head ? but it was impossible to ignore her wails, soon melting as candle wax into gurgling bubbles. My heart skidded into my throat, battering against the back of my skull, and I knew exactly what was happening. Frank was going to kill her, and I had no way to stop it. The only thing I could do was let out a croaky “Mom!,” my tongue sticking to the roof of my mouth. And it must have been a bit of witchy magic, because his grimy grasp instantly released from around her neck. She gasped. She gasped like a fish out of water, puffing its lips for the sweet nectar of a nearby stream. A man of meager frame, he came charging bullishly down the hallway in nothing but an open robe.

It was the most terrifying night of my life.

I was born into domestic violence. Many of my earliest memories were littered with abuse, predominantly physical. One of the hardest to forget was the evening I was joyfully playing with Ken & Barbie when my father grabbed his belt, lassoed my sister like he was herding cattle, and beat her senseless. But there remain deep psychological and emotional scars from which I may never recover. Bursts of brutality weren’t the only things I had to dodge as a young kid growing up in West Virginia. It was frequently the quieter moments, when it seemed everything was good again, yet there was the constant fear that one wrong word or move could ignite utter bedlam.

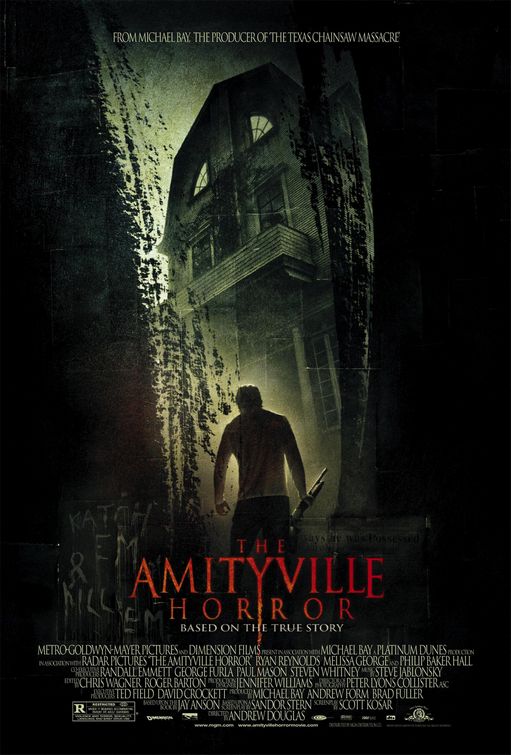

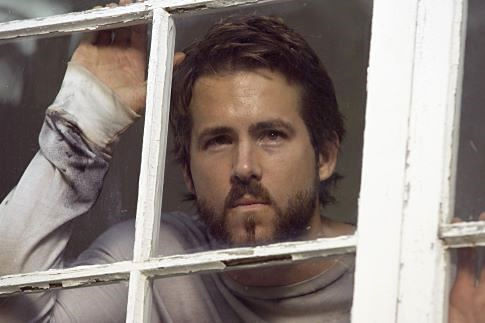

During my recent binge of the entire THE AMITYVILLE HORROR series (including the many DTV releases in the late-aughts and 2010s), I was once again reminded of the sheer terror hiding behind Ryan Reynolds’ eyes. The 2005 remake (directed by Andrew Douglas) of the 1979 classic carries with it a particular anvil-sized approach to the story of Ronald DeFeo Jr. and how he murdered his entire family in 1974. But the real life tragedy is of little importance in the context of domestic violence here. When George (Reynolds) and Kathy Lutz (Melissa George) move their family into 112 Ocean Avenue, an insidious form of abuse seeps into the floorboards, oozing like blood from the walls, as it pops out nails and other structural rivets, metaphorically speaking.

Things, as they do, happen gradually. Career tensions, friction from the move into a new neighborhood, and simple everyday frustrations burst to reveal pus-filled sores and the sort of unbridled rage that almost feels primal and unnatural. I had one visit with my mother after the choking incident, and I can still feel Frank’s eyes, dark and swirling masses containing something truly sinister, burrowing into my skin, a sly curl to his lips when he greeted me. I have chills as I sit here, walking my mind back to that cursed night. He could have very well killed us both, I know that now, but he didn’t. And for that I am thankful.

The film’s descent is slow and methodical, like peeling back decades-old wallpaper stained with cigarette smoke. Underneath, there’s only parasites that have turned once-lush and beautiful hardwood into stinky, mold-ridden cheese. Within a few days, George complains about the cold, a shiver galloping along his spine, and he heads downstairs to restock the furnace with fresh wood; it is within this moment, when he hears demonic voices slipping out of the air ducts, worming into his ears, that a switch flips in his brain. Later that night, as he’s having raunchy sex with Kathy, he sees his first ghost: the tortured little girl Jodie with a hole in her head. “I don’t feel well,” he says, a little disheveled.

A few days later, George reprimands Michael (Jimmy Bennett) for going down into “my office,” he spits through a clenched jaw, to retrieve a rusty, nondescript torture device, but he quickly apologizes for his behavior, as all abusers do. As the house is once again shrouded in darkness, Kathy discovers George huddling beneath a blanket in the basement. “It’s the only place that’s warm in this damn house,” he huffs. He can’t sleep, he continues. Kathy tries to comfort him, cooing, “I’m sorry, baby.” “Um, don’t talk to me like I’m one of your kids, okay?” he seethes back. Kathy’s face twists in confusion; it’s a kind of response she’s not used to hearing from her darling husband.

Some time later, George and Kathy hire a babysitter so they can enjoy a romantic dinner out with good food and good wine. “I feel better. I think I just needed to get out of that house,” sighs George, shaking his head in relief. Over the course of the evening, he waxes truly charming, hypnotic even, as he reminds Kathy exactly why she fell in love with him in the first place. “I’m going to spend the rest of my life making you happy,” he promises. Kathy, clearly smitten, and perhaps a little drunk, is swept off her feet. Abusers will do that, you know, pour on the charisma as they profess their undying love, and hope their empty promises make you forget all about the abuse.

Countless other smaller moments, from George spitting out Kathy’s meatloaf dinner to declaring “I’m doing the discipling from now on,” build a foundation for a volatile house of abuse. By the third act, true evil has fully manifested. One particular moment that remains seared into my head involves Kathy’s other son Billy (Jesse James). When George forces him to hold blocks of wood so he can chop them into splintered fragments, goosebumps pop into the back of my neck. The emotional trauma in that moment, as George then grabs Billy’s face, gritting his teeth, and spewing, “We’re friends. We’re having fun, right?” is blood-curdling. It’s exactly what it’s like being trapped not only in those moments in real life but the memory of it all. It haunts me sometimes, and I dream about it ? not often, but I do. It’s like Frank is a soul-sucking ghoul whose sole purpose is to drain me of my energy; and that says nothing about the damage done to my mother, who I’ve watched struggle with alcoholism ever since.

THE AMITYVILLE HORROR released only seven short years after Frank nearly killed my mother. It was Thanksgiving in 1998 when I heard the news. I was perched upon my grandmother’s emerald green couch, watching TITANIC, of all things, when my grandmother came into the room to tell me my mother was in the ICU with a broken jaw. My blood ran cold. I have few details of that night, how he hit her so hard she went flying across the room and how fearful she was. Frank was so consumed with paranoia that she was cheating on him with another man that it sent him into a rage-filled stupor. When George hunts down his family, forcing Kathy to grab a rifle and defend herself and her kids at all costs, I’m instantly reminded of what it must have been like that night. When Frank, wild-eyed and crazed, came at my mother, what did she do? What thoughts ran through her head? Did she think she was going to die that night?

As a 30-something adult now, I’ve wanted to ask deeper questions about what actually happened, but I know it’s not my place to reopen her trauma. Maybe she’ll tell me herself one day, or not. That’s resolutely her story to tell, and all I can do is tell mine. The residual effects of domestic violence, from both Frank and my own father, have tortured me for decades. I still have plenty of issues through which to work, and thank god, we have horror films that are cathartic and healing and empowering. I don’t know where I would be without them. And I count THE AMITYVILLE HORROR, both the original and the remake, as crucial to my ongoing journey to redemption.

Tags: Andrew Douglas, Chloë Grace Moretz, Dimension Films, Horror, Jay Anson, Jesse James, Melissa George, Peter Lyons Collister, Philip Baker Hall, Platinum Dunes, Rachel Nichols, Ronald DeFeo Jr., Ryan Reynolds, Scott Kosar, Steve Jablonsky, true crime, We Are Horror

No Comments