Content Warning: This article contains frank discussion of suicide.

A couple of years ago, I told a friend of mine that the question wasn’t if I would kill myself, it was when. Though I’m in a good place right now (ironic, perhaps, given my father’s recent death), deep down I still think that’s true. As someone who’s struggled with depression and feelings of worthlessness for longer than I’ve had names for those feelings, I am acutely aware that, even on good days, thoughts of suicide are always lurking in the shadows of my mind. So when I first watched THE SEVENTH VICTIM years ago and heard Jacqueline (Jean Brooks) say, “I’ve always wanted to die. Always,” I understood her character’s resignation to her fate on a cellular level.

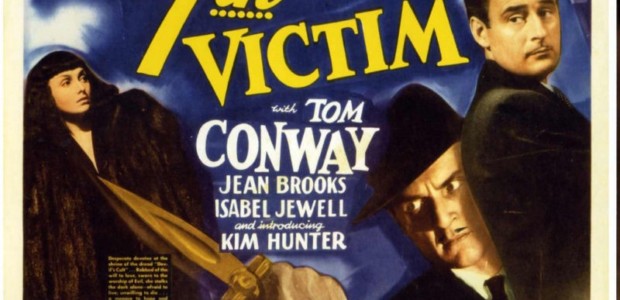

Jacqueline still mystified me, though. She’s an enigmatic figure: Brooks is the ostensible star of the film, but her screen time is surprisingly brief. When she finally appears, she’s an eerie cipher, showing up to put a finger to her lips then vanish just as quickly as she materialized. The plot largely follows her sister Mary (Kim Hunter) as she investigates Jacqueline’s disappearance and discovers that her sister is embroiled in a Satanic cult that wants her dead. It’s a mesmerizing and gorgeously shot film that perfectly balances horror and film noir while dealing with issues of mental health, artistic frustration, and repressed queerness.

Movies don’t change, but we certainly do: you’re a different person every time you watch a film, and that can change how you relate to the images playing across the screen. The first time I saw THE SEVENTH VICTIM, I identified far more closely with Mary than with Jacqueline. Like me, Mary is the younger of two sisters. Like me, Mary is sweet and pleasant whereas her sister is striking and fascinating. Like me, Mary wants to be a good girl and do her duty by locating her sister. Though in Mary’s case it’s a literal question — for most of the film, she has no clue where Jacqueline is — it’s more of a philosophical question for me. My sister and I have never been close. Though I love her, she’s just as much a puzzle to me as Jacqueline is to Mary: “It’s almost as if I’ve never known my sister.”

Though “sweet and pleasant” might sound like endearing personality traits, in my case they may actually be defense mechanisms. Childhood trauma left me pathologically eager to please. Some days I’m still not sure what my real personality is because I’ve based my whole identity on being the person that other people wanted or needed me to be. Growing up, I was the good child because my sister was (according to my mother, at least) a rebellious hellraiser who caused untold grief in her late adolescence. To earn my mother’s love and acceptance, I assumed that I had to be the opposite of my sister. Where she rebelled, I obeyed; where she followed her own path in life, I followed my mother’s. I learned to push down the voice in my head telling me that I was monstrously unhappy. Instead, I listened to my mother’s voice telling me that I was the good daughter, the normal daughter, the sane daughter.

Unsurprisingly, that didn’t work out well for me. My sister is now happily married with two beautiful children and a thriving career. I, on the other hand, am divorced, broke, and mentally ill. I’m the “crazy” sister now. I’m the defective one. I may not have Jacqueline’s beauty or fashion sense, but I do have her desperate search for meaning, her inability to connect with the people around her, and her unshakable belief in the inevitability of her own suicide. Watching the film now, I identify less with Mary’s humble tenacity and more with Jacqueline’s inscrutability — if I don’t know who I really am, how can anyone else hope to know me?

Like Jacqueline, I’m not even the star of my own movie. I don’t feel present in my own life…I exist, but I don’t live. I’ve built so many walls to protect myself that I don’t know how to tear them down to let others in. Jacqueline’s uniquely styled raven hair and pale skin make her look like a ghost. When she flees the cult after they urge her to drink poison, she runs down the street and looks pleadingly into the face of every person she meets, searching for help and understanding but finding only disinterest or mockery. The passersby ignore her or misunderstand her intentions. The scene perfectly encapsulates what it feels like to suffer from depression, anxiety, and trauma: ever the ghost, Jacqueline finds herself alone even when she’s running down a busy street.

My world shifted on the day I realized that, despite (or perhaps because of) my desperate attempts to live the life I thought I was supposed to live, I had become the “bad” sister. Rewatching THE SEVENTH VICTIM in the wake of that realization was just as devastating. Nearly everything I had believed about myself had changed. I could no longer see myself in the best parts of either Mary or Jacqueline. The only constant in my relationship with the characters in THE SEVENTH VICTIM is my grim intimacy with the suicidal urges that lie waiting for me. Just like Jacqueline, “I run to death, and death meets me just as fast.”

No Comments