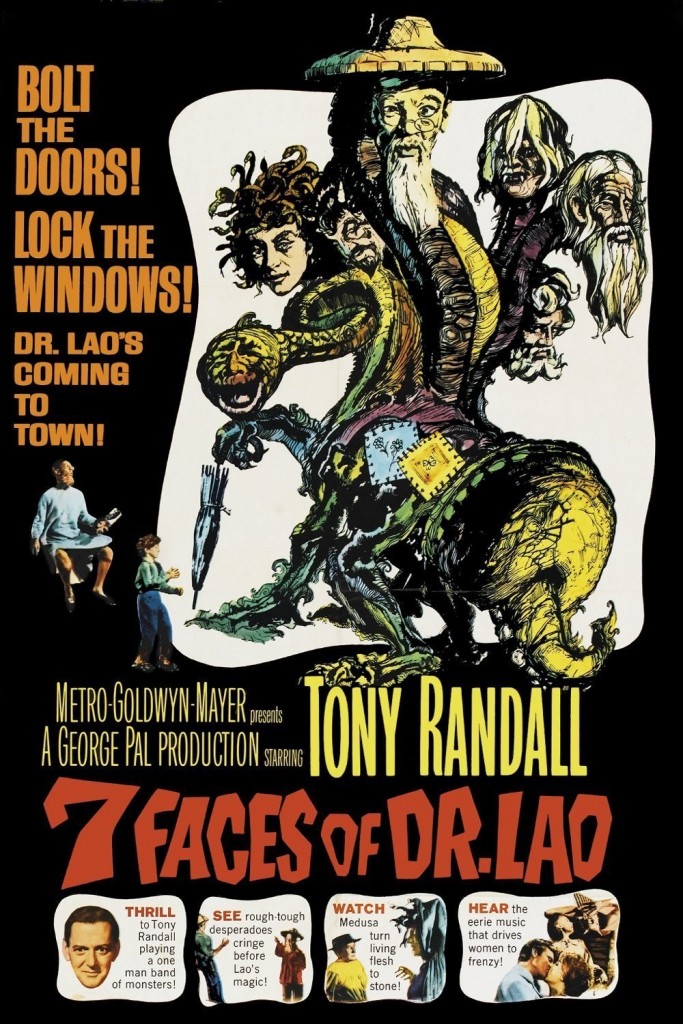

When I was growing up, there were two movies that I’d happily watch over and over—which was convenient, as local TV stations often replayed them in the afternoon. One was THE TIME MACHINE, and the other was 7 FACES OF DR. LAO. I was quiet and introspective, and there was something about the rich imagination on view in both those films that appealed to a dreamy kid like me. It wasn’t till much later that I noticed that both films shared the same director: George Pal. And then I noticed his name was on a slew of other films I loved, including THE WAR OF THE WORLDS, as producer.

New York Times critic Howard Thompson’s notice was pretty typical: “As directed and produced by George Pal, it is heavy, thick, pint-sized fantasy, laid on with an anvil. … As the focal point, got up in seven different guises with accents to match, Tony Randall is excruciatingly coy and simpering. Mr. Randall is, in fact, about the cutest thing to hit the screen since Shirley Temple. Obviously, he knows it, too.” Ouch.

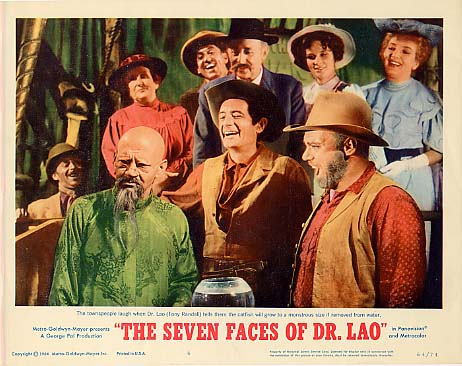

Perhaps it’s just nostalgia kicking in, but to my eyes, the film holds up quite well. Randall is indeed a ham, but his various performances work. (He’s credited with the seven roles of Lao and six of the circus’s acts, hence the title, though online sources say the Abominable Snowman was really played by a stuntman, and Randall provides only the voice of a stop-motion snake. He can also be glimpsed as a silent eighth character, a disapproving audience member watching the circus acts perform.) To modern sensibilities, the thought of a white actor playing the Chinese main character may rankle, but the characterization plays fairly subversively. When we first meet Lao, he seems a cringe-inducing racist caricature—but it soon becomes clear that Lao only speaks and acts like a stereotype when he’s talking to someone who expects him to do so. Otherwise, Lao speaks without an accent and drops the physical shtick. That is, the character is consciously playing to an audience, aware of what they think of him and responding in a way that gives him the advantage.

Furthermore, the film makes it clear early on that it’s on the side of Lao, not the closed-minded inhabitants of the film’s small-town setting. Soon after the character is introduced, he is spied by three buffoonish townspeople. “Who’s that, anyway?” asks the first. “I don’t know. Looked like a Jap to me,” replies the second man. “He’s Chinese,” states the third. “How’d you know?” asks the second. The third man’s reply: “Because I ain’t stupid.” It’s pretty clear that the filmmakers’ intent isn’t racist, even though the racial aspects of the film can produce some discomfort to modern eyes. Certainly, Randall’s performance as Lao is a far cry from Mickey Rooney as the bucktoothed Japanese stereotype in BREAKFAST AT TIFFANY’S.

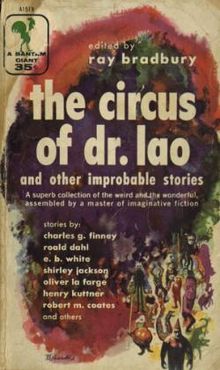

For some reason, it took a long time for me to catch up with the source material for the film, Charles G. Finney’s 1935 The Circus of Dr. Lao (this despite the fact that I’ve always had a fondness for novels about sinister carnivals and circuses, including Tom Reamy’s Blind Voices and, more recently, Brooke Stevens’s Circus of the Earth and Air). And when I finally did, I was surprised by the novel’s dark, nihilistic tone. The atmosphere of Circus is so far from the sentimental take of 7 FACES, I’m surprised that anyone reading the book would think it would be a good basis for a family-friendly film.

Aside from the novel’s tone, it’s also completely plotless. Lao comes to town and sets up the circus, the locals interact with him and his performers, and after a chaotic presentation about the fall of the fictional land of Woldercan, the circus abruptly disappears and the people of Abalone, Arizona, “went homewards or wherever else they were going.” In a strikingly postmodern coda, Finney lists the characters and some of their backgrounds and fates (for example: “THE DEAD MAN APOLLONIUS BROUGHT BACK TO LIFE: Arnold L. Todhunter. … He said heaven reminded him more than anything else of an advertisement he had once read of Southern California.”), various foodstuffs consumed (“Soda pop. Sea foods. Carbohydrates. … Little fat brown boy.”), and points out the novel’s “contradictions and obscurities.” Among them: “If the circus didn’t come to Abalone on the railroad and didn’t come on trucks, how did it get there?” It’s not intentional, but this section looks like the kind of thing that books often now include to spur discussion at book clubs.

The town’s inhabitants are mostly an ignorant, uncurious lot. They gaze at the circus’s true wonders but don’t appreciate them. Magician Apollonius miraculously pulls a baby pig out of a small bag of candy, and the mother of the child for whom he performed this miracle complains, “Oh, goodness. We haven’t room for a pig, really. Our place is so small, you know.” Apollonius replies, disappointed, “Um. What a pity. It was such a nice pig, too.” When he then makes a huge, mysterious-looking flower appear, and the same woman calls it a trick, he clarifies: “Oh, these aren’t tricks, Madame. Tricks are things that fool people. In the last analysis tricks are lies. But these are real flowers … and that was a real pig. I don’t do tricks. I do magic. I create; I transpose; I transubstantiate; … but I never trick.” But his audience remains largely unmoved. Even when Apollonius makes a man rise from the dead, it hardly causes a stir.

Characters don’t do much in the way of learning or growing. They meet Lao’s performers, are puzzled (or annoyed) by them, and move on. The structure is very episodic, with little forward momentum. Not that that matters—given the book’s short length, the lack of plot isn’t much of a hindrance. The Circus of Dr. Lao feels more like a long short story than a short novel. The reader is introduced to Lao and his wonders and—poof!—the circus is gone without overstaying its welcome.

It’s worth pointing out, though, that while the novel’s take on Lao himself is similar to the film’s—that is, Lao is fully aware of the stereotypes in the minds of the townspeople and plays with them as needed—the description of the peepshow presentation of a fertility ritual of some African natives is jaw-droppingly racist. “Around an old grass hut three Negro priests were dancing beneath a symbol of striking masculinity. … They threw off their grass skirts, dancing nude under the huge lingam, their black hides greasy with the rain.” And it gets worse from there. Obviously, this sideshow attraction was not used in the film.

Finney’s novel was adapted for the screen by Charles Beaumont, perhaps best known for his many scripts for The Twilight Zone. That’s not surprising, as the film resembles some of the more whimsical episodes of that series. (Online sources also list Ben Hecht for doing uncredited work on the script.)

Beaumont approached his adaptation by making several changes and additions. For starters, the film is set in an unspecified past that appears to be some time in the mid to late 1800s; based on contextual clues, I’d say the novel is set either in the “present” of the novel’s 1935 publication or perhaps a little earlier. But more importantly, the film has an overarching plot. The villain of 7 FACES OF DR. LAO is Clint Stark (played by Arthur O’Connell), a wealthy man who tries to convince everyone in Abalone to sell their homes to him. He makes up a story about a crumbling pipe that feeds the town water being too expensive for the townspeople to fix. It’s a lie, though—really, he’s been tipped off that the railroad will soon be coming through, making property much more valuable.

Stark isn’t the only character that Beaumont invented for the film. Ed Cunningham (played by a bland Jon Ericson) is the town’s newspaper publisher, determined to expose Stark’s plans. Angela Benedict (I Dream of Jeannie’s Barbara Eden, who gives a strong performance) is the town librarian, a widow, and the object of Cunningham’s affections. (There’s a character analogous to Benedict in the novel, Agnes Birdsong, but with a somewhat different background.) And Mike Benedict is her son, around 10 years old, who becomes a protégé for Lao.

Many of the novel’s scenes appear in the film somewhat changed and with a different focus. For instance, in the book, Agnes Birdsong happens into the tent with the circus’s satyr and is ravished by him. “The spittle on his lips mingled with the perspiration around her mouth, and she felt that she was yielding, dropping, swooning, that the world was spinning slower and slower, that gravity was weakening, that life was beginning.” But there’s no real change in Birdsong after this scene.

In the film, Angela Benedict is a lonely widow with a full-time job and a kid and mother in law to take care of. She’s closed off from life, and won’t consider going out with the newspaper publisher, despite the urging of both her son and mother in law. When she swoons as the satyr dances around her, the satyr momentarily turns into Cunningham. The experience changes her, making her realize she’s too young to give up on love, which gives the film a little forward momentum.

The film, like the book, has its climax as Lao gives his presentation on the people of Woldercan. In the book, the story of Woldercan doesn’t seem to have much point—it’s just another one of Lao’s wonders—and the story ends abruptly. But screenwriter Beaumont has the people of Abalone see themselves in the people of Woldercan, whose story turns in to a fable mirroring what the townspeople are facing with Stark. The people of Abalone suddenly, and without explanation, then find themselves transported to a town meeting to vote on Stark’s proposal. Stark loses and confesses why he really wanted to buy the town. In a denouement that’s not in the novel, Stark’s henchmen (one played by Royal Dano, veteran of many a western) are angered by their boss’s change of heart and destroy Lao’s circus tent, unleashing the Loch Ness monster in the process. Mike sees this and gets Lao, who sets off a rain-making machine, which shrinks the monster back to the size of a goldfish. It’s a fun sequence, and it arrives at point where the film could use a jolt of energy. The next day, Lao rides off on his donkey, leaving the town (especially Ed, Angela, and Mike) changed.

Is the film corny? Oh, yes, absolutely. In fact, it’s super corny, but it’s also a strong example of a well-constructed piece of mass-appeal entertainment. (Not too appealing, though, as the film was not a box-office winner at the time of its release. Still, judging by its near ubiquity on TV when I was growing up, kids must have loved it, and it has strong reputation today.) All the parts of the machinery of the film work, if you can, yes, get beyond the fact that Tony Randall is playing an ancient Chinese guy (and can excuse the film’s more saccharine moments). The film, for all of its hewing to convention, can also be surprising. For instance, the scene in which the satyr puts Angela into a rapture is startlingly sensual for a 1964 family film.

I first read Finney’s novel a few years ago, and did not like it—at all. In fact, I pretty much had to force myself into finishing it. (I can be that way with books—I’ll happily stop watching a film I’m not enjoying, but somehow feel bound to finish books, unless the problem is that I’m merely bored with them.) Given the warm nature of the film, the book’s dark tone took me off guard. But upon rereading The Circus of Dr. Lao in preparation for writing this article, I was actually shocked by how much I enjoyed it, once I was able to meet the book on its own terms. It’s dark, yes, but it also features some spare, truly sharp writing, and Finney is terrific at conjuring up some wonderfully bizarre images. (Artist Boris Artzybasheff’s original illustrations, thankfully included in the 2002 Bison Books reprint, are also beautiful and strange.) My original dislike of the novel came from my love of the film—but that was my problem, not the book’s. Pal and Beaumont’s LAO isn’t Finney’s Lao, but both are compelling creations.

— Jim Donahue.

BUY THE MOVIE!

BUY THE BOOK!

LOOKING FOR UNDERGROUND CULT MOVIES, DVDs, LIMITED VHS & OTHER COOL STUFF.

CHECK OUT THE DAILY GRINDHOUSE/CULT MOVIE MANIA STORE

Tags: Adaptations, Barbara Eden, Books, Charles Beaumont, Charles G. Finney, George Pal, Movies, Tony Randall

this movie is so awesome!

Great review of a lifelong top-ten movie. Thanks.