In most fields of entertainment and/or artistic expression (the two only seem mutually exclusive, they needn’t necessarily be), there is usually at least one generally-acknowledged “Master of Horror,” if not several : literature has Stephen King; cinema has John Carpenter remaining out of the one-time Carpenter/Craven/Romero “trinity,” with plenty of others ready and waiting to assume up the mantle; television has Robert Kirkman (hey, I didn’t say I liked all these folks); mainstream comics still clings to the acclaimed works of “British Invaders” Alan Moore, Neil Gaiman, and Jamie Delano, as well as to the legendary EC and Warren creators. Purportedly “alternative” or “independent” comics, though? Not so much.

Certainly the first wave of underground comix saw plenty of cartoonists who were very much at home delineating the horrific : Greg Irons, Jack Jackson, Spain Rodriguez, S. Clay Wilson and all produced memorable horror-themed works — heck, even a young Richard Corben cut his teeth in the underground milieu. These days, though, folks pursuing a non-corporate path for their comics careers tend toward the autobiographical, the surreal, the “slice-of-life,” the dramatic, the melodramatic. Horror seems to have fallen somewhat out of favor among the “indie” set.

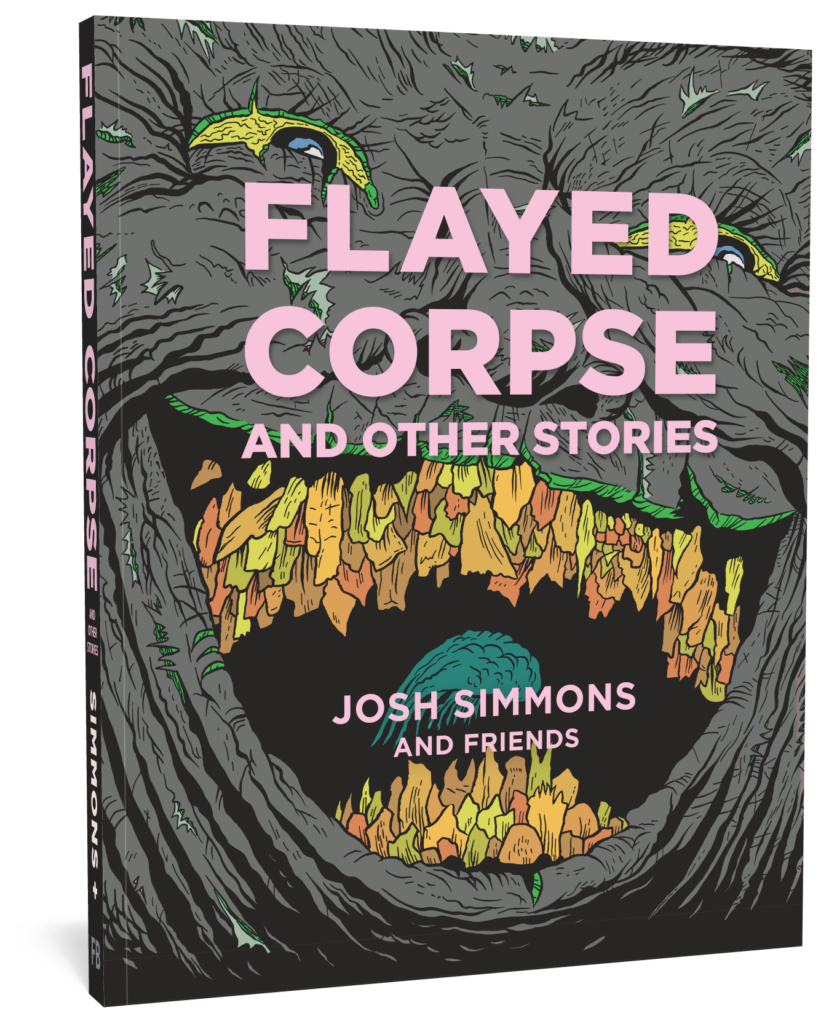

Which is why Josh Simmons is such a breath of fresh — if fetid and diseased — air. Whether we’re talking about his shorter works collected in books such as The Furry Trap, or long-form graphic novels like Black River, this is a guy who makes his bread and butter holding a brutally scrambled — and just as brutally honest — funhouse mirror up to society and forcing us to acknowledge any number of things we’d much rather ignore, and his latest Fantagraphics-published collection, Flayed Corpse And Other Stories, sees him back on familiar ground and twisting the knife in deeper.

Simmons is often mistakenly lumped in with the “dudebro” crowd of white male cartoonists that think subtracting all meaning from their work automatically makes it “edgy” and gives them license to “up the ante” (Jason Karns, I’m looking at you — and Charles Forsman, I’m looking at you sometimes), but what I think the largely-well-meaning critics who take exception to this (as, usually, they should) miss is that there are ways to make pointlessness a point in and of itself, and that it takes genuine skill to effectively imbue your work with a sense of dread at the realization that the world is going to go on spinning no matter what the hell happens to any of us individually. That’s what Simmons does, and he does it without apology, pity, or a minute’s hand-holding.

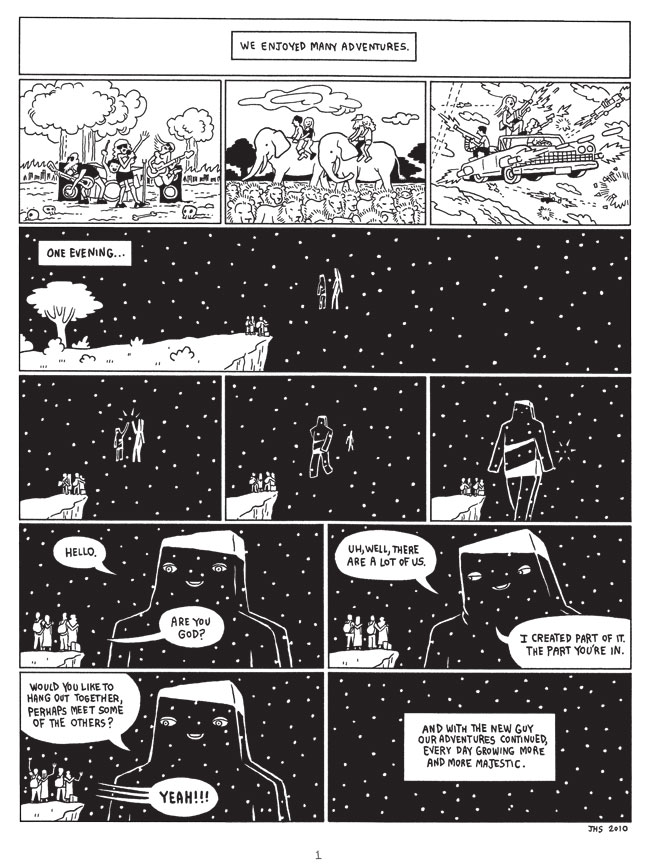

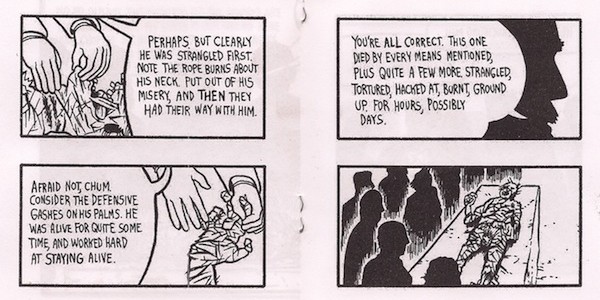

His intro strip to this volume, pictured above, subverts the contents of everything that follows for those of us who know what to expect, saves its sardonic punchline if you’re a newbie, but undoubtedly works like a charm (an unlucky one, perhaps, but still) either way and very nearly manages to momentarily redeem the concept of irony until you remember that, oh yeah, most people shouldn’t even try this shit, but Simmons does it well enough to earn a pass. It’s really the first (and titular) strip presented after the table of contents, then, that sets the “legit” tone for the next one-hundred-sixty-some pages, as medical examiners debate how an unfortunate corpse came to be in their “care,” each one-upping the other with increasingly grotesque hypotheses as to cause of death before settling on all of them, and that the victim therefore met his end in a state of extreme agony — an agony that will likely endure forever because, I guess, that’s how metaphysics works. Welcome to a highly personal apocalypse that never ends.

Bizarrely, though, Simmons and his coterie of collaborators — writer/artist Tom Van Deusen, inker Eric Reynolds, artists Patrick Keck, Ben Horak, James Romberger, Pat Moriarty, Eroyn Franklin, Ross Jackson, and Joe Garber (with additional stand-alone art pages by Tara Booth, Anders Nilsen, and Shanna Matuszak) — find the funny side in the midst of this bleakness. The humor on offer is of the unsettling — hell, the gallows — variety, to be sure, but sometimes a shameful laugh in spite of yourself is better than no laugh at all.

In that sense, then, this assemblage of stories — most culled from various anthologies published between the years 2010-2017, although some were self-contained “floppy” single-issue releases — probably owes more to the ethos and aesthetic of the drive-ins and grindhouses of the ’70s than it does to what’s happening in contemporary horror, given that anything can happen at any time and no one is safe. Joe Bob Briggs would probably approve — as do I — but folks who grew up on horror with implicit, if never directly-stated, rules ? The readers who know the “loose” girls die first, the virgins survive until the end, the killer gets up and walks again no matter how violently he’s been dispatched? They might be genuinely surprised by the kind of “no hope for anyone, ever, so don’t fucking kid yourself” existential terror that is Simmons’ stock in trade.

I really don’t want to give the impression that this book has a sense of relentlessness to it, though — and while much of that is down to the aforementioned bleak humor, a lot of it is down to the varying, but uniformly pitch-perfect, art styles on display. Simmons’ own cartooning is plenty strong in its own right — rich and inky blacks juxtaposed with economic, effective, and moody linework that gives off a feel of “what if Chester Brown swapped out his clinical detachment for informed cynicism?” and finds its apex in the collection’s two finest stories (“The Incident At Owl’s Head,” a revisionist take on outsider-wanders-into-an-isolated-community tropes, and “Seaside Home,” a harrowingly straightforward character study of a family facing unavoidable, inescapable natural disaster) — but he shows a real penchant for playing to his artists’ strengths when he sets the pencils and brushes aside himself.

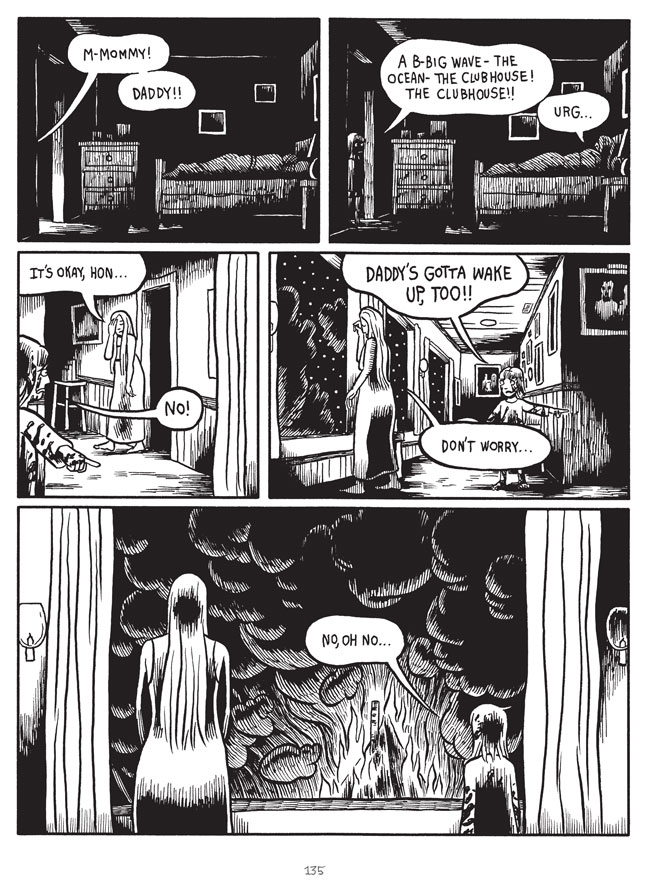

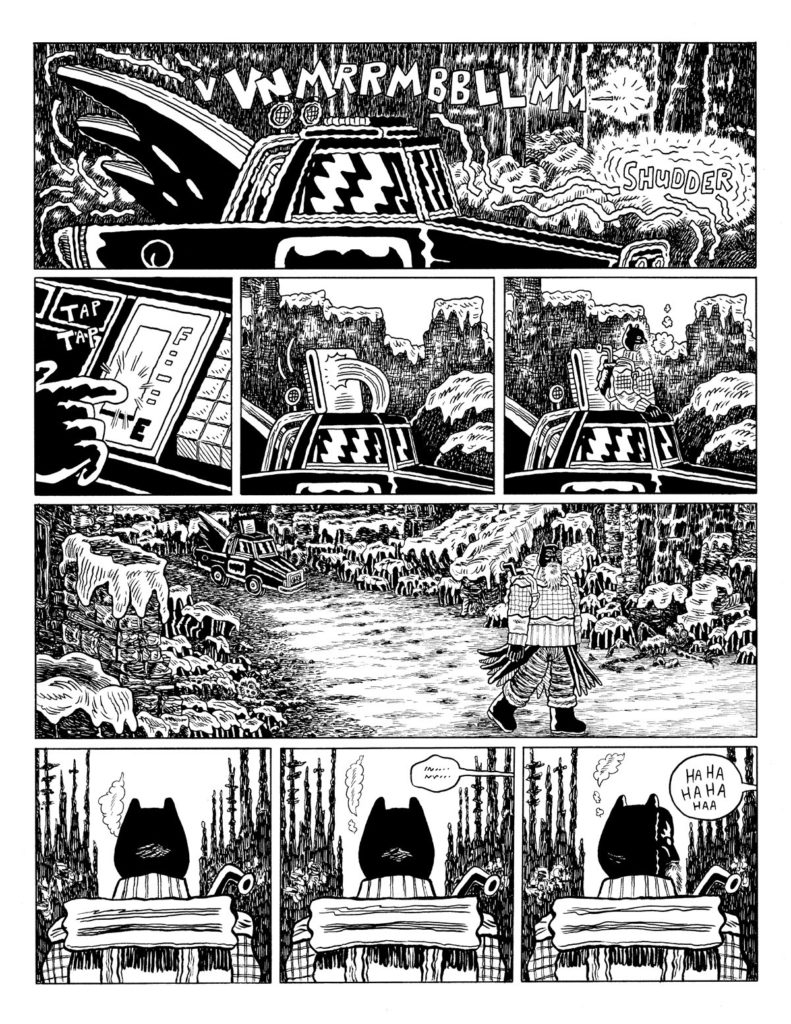

Of the collaborative entries, the strongest is no doubt “Twilight Of The Bat,” the justly-celebrated story that draws the one and only logical conclusion to the let’s- not-call-him-Batman and let’s-also-not-call-him-Joker relationship (something of a surprise entry given that the original, riso-printed magazine came out in the latter part of 2017 and is still available from its publisher, Cold Cube Press), drawn with suitable post-apocalyptic grit by Patrick Keck, while the best example of two heads being better than one is probably “Daddy,” a stark and particularly unforgiving tale of the “oh my God the killer was already in our home” variety that transcends its telegraphed-from-the-outset trajectory thanks to James Romberger’s violently evocative art that marries old-school EC eeriness with a thoroughly modern sensibility, all awash with rich and vibrant and frankly disturbing colors. It’s gorgeous to look at, yeah, but that doesn’t mean it doesn’t hurt like hell.

Still, while the gory and the gross are present and accounted for here in generous proportion (see especially the Pat Moriarty-illustrated “The Great Shitter”), it is the philosophy underpinning Simmons’ stories that sets them apart and above. Not even the light-hearted (relatively speaking, mind you) Tom Van Deusen-penned yarn, “Late For The Show,” can completely escape the inexorable vortex pull of inevitability at the core Flayed Corpse And Other Stories. When your number is up, it’s up, Simmons never tires of reminding us — but before it comes up (and I hope, for your sake, that’s not for a good, long while yet), I absolutely urge you to buy this book.

Tags: Columns, Comic Books, Comics, Fantagraphics Books, Josh Simmons

No Comments