David Lynch is not widely considered to be a horror director. He’s generally categorized as an art-film director, a surrealist. His movies capture the lyricism and the bizarre, vague symbolism to be found otherwise only in dreams. But when you’re dreaming, it’s not always a restful experience. Sometimes your dreams are more like nightmares. And few directors are as effective at conjuring the experience of nightmares onscreen as David Lynch is.

Most people (myself excluded obviously) don’t have recurring dreams about great white sharks or masked murderers. Most people’s nightmares are far more surreal, non-linear, and oblique than your general straight-forward horror-film narrative. Nightmares are often scary precisely for how much sense they don’t make: The lack of clarity, the sense of confusion, that adds to the uneasiness. Like a dream or a nightmare, you walk away from a David Lynch film struggling to parse with what you’ve experienced — you may not be able to easily describe the events of the story to a friend, but you often feel affected, even disturbed.

Lynch has said of his writing process: ”If you want to make a feature film, you get ideas for 70 scenes. Put them on 3-by-5 cards. As soon as you have 70, you have a feature film.” That may well be true. Lynch’s films aren’t tightly-plotted in a classical sense — to say the least. However, this well-travelled quote undersells Lynch’s abilities as a filmmaker. The reason why he has been as well-reviewed as he has throughout the course of his career is because he is an excellent director. He knows how to orchestrate a film, gathering all the elements — performance, costuming, camera movement, lighting, atmosphere, pacing, sound design, and score — in order to create a mood. And sometimes, in his films, that mood is horrifying. It takes skill and methodology to make a scene scary; it doesn’t happen by idling recording a bunch of shots and scenes.

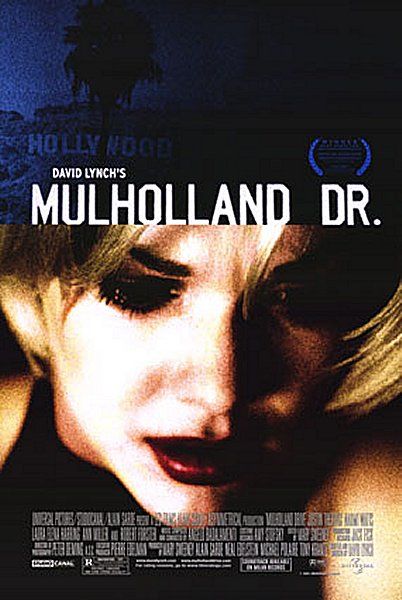

2001’s MULHOLLAND DR. is a perfect example of this methodology. Again, it isn’t a textbook example of a traditional horror film, but it surely contains individual scenes of intense horror. Please also note that cinematographer Peter Deming , who also shot the even more terrifying LOST HIGHWAY for Lynch, is otherwise a horror veteran, having shot both EVIL DEAD II and DRAG ME TO HELL for Sam Raimi. MULHOLLAND DR. has been described as :a surrealist neo-noir” (Wikipedia) or “a poisonous valentine to Hollywood” (J. Hoberman), both of which it is, although it’s also more.

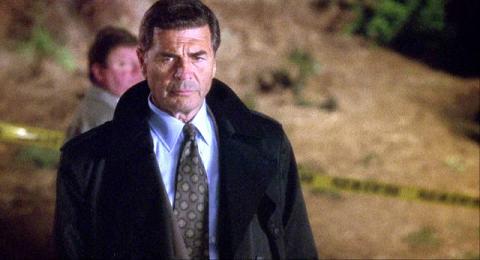

It’s the story of Betty (Naomi Watts), whose name may actually be Diane, an aspiring actress in Los Angeles who encounters a mysterious bombshell with amnesia who takes the name “Rita” after seeing a poster for GILDA, starring Rita Hayworth. The actress, Laura Elena Harring, does indeed resemble Rita Hayworth, which is one of many layers of old-Hollywood history layered onto the film. Betty lives in an apartment complex with “Coco”, who is played by a now-elderly Ann Miller, a dancer and singer with a long resume of classic-musical credits. Chad Everett, a onetime megafamous TV actor, plays a fictionalized version of himself as the actor who Betty reads lines with at a big audition. The denouement of that sequence is contemporary in a way that undercuts the more recognizable set-up, which is classic Lynch method. And the great Robert Forster appears as a police detective, referencing his own genre-film history and linking MULHOLLAND DR. to the Hollywood of the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s.

Lynch’s way is often a process of stripping away the bright-eyed, blindly optimistic veneers of America in order to show the darkness underneath. Is it an accident that the blond ingénue named Betty is contrasted against a dark-haired counterpart (a Veronica, if you will)? The G-rated Archie Comics veneer very quickly ends up in pointedly sexual territory. To put it bluntly: Betty and Veronica hook up. But in Lynch’s hands, it doesn’t play like a fanboy fantasy — it’s dark and disturbing, leading to heartache and ruin. There’s an overwhelming eeriness to the sexuality in MULHOLLAND DR., and then you have some seemingly-unrelated and straight-up spooky horror scenes sprinkled throughout.

Take the infamous diner scene. A young man (played by Patrick Fischler, a character actor who specializes in nervous and unsettled types) sits down with a friend at a restaurant called “Winkie’s” on Sunset (clearly meant to be a Denny’s) to talk about a dream he had. In the dream, he was in this very diner, with this very friend, and he was scared. The scene starts innocuously, with the camera stationary focused on either face. As the young man begins to relate the dark side of the dream, Angelo Badalamenti’s score enters the scene, mixed with a kind of drone in the sound design. The camera moves closer on the two faces, uneasily swinging from side to side. The young man describes a figure behind the diner, a man with a horrible face which he hopes to never see outside of that dream. The friend suggests they go check it out. The camera follows them both outside at a measured pace, the sound drone intensifying. The young man is sweating as the two of them approach the graffitied corner. Suddenly, a haggard-looking man steps out from behind the corner, the music suddenly bursts out from a drone to a spooky blast, and the young man passes out from fright.

This is a horror-movie scene, unquestionably. And really, Lynch has scared us using almost nothing. It’s two guys in a diner, and they go outside and see an untidy vagrant. That’s it. The man behind the diner is no Lou Diamond Phillips, but neither does he have a face much scarier than any mask at a discount Halloween store. The fright that the audience feels — and nearly everyone I’ve ever talked to about this movie is petrified by this scene — is exclusively created through the determined use of performance, costuming, camera movement, lighting, atmosphere, pacing, sound design, and score. Lynch can do sweetness and symbolism as well as any director, but so too can he conjure up true horror out of everyday scenarios, without any expensive visual effects. If he ever made a full-on horror movie, he’d blow everyone’s minds out the window.

This particular scene I’m talking about, the diner scene, initially seems to have little to do with the rest of the narrative. In part, that’s a result of the troubled production of the film, which Lynch envisioned as a television series and was filmed as a pilot. Lynch ended up having to re-edit the pilot and shoot additional scenes in order to re-conceive it as a feature. Of course, even as a TV serial it’s possible this scene could have played out of context. As it happens in the film, it’s framed in a way suggesting it’s Rita’s dream — you see her settling in and closing her eyes before the diner scene, and you see her sleeping again after it ends. Why is Rita dreaming about this funny little guy in a diner and his own crazy dreams? There’s probably a reason. Or there isn’t. It kind of doesn’t matter too much.

A lot of people, from undergraduate film majors to professional critics, spend a lot of time evaluating the possible meanings of David Lynch’s films. I spent a fair amount of time doing that myself, before ultimately deciding that the intended meanings, and also the unintentional meanings, of the imagery and the dialogue and the events of Lynch’s less-than-linear films are almost beside the point. The late, great Roger Ebert backed this theory up when he wrote of MULHOLLAND DR. that “the movie still plays–like a movie. Every individual sequence is satisfactory and effective in and of itself.” He’s right about that, I think. Just to use the example I described, you can watch that diner scene within the context of the full running time of MULHOLLAND DR., or you can watch the five-minute scene on its own: Either way, it’s probably going to scare the shit out of you.

MULHOLLAND DR. is the midnight movie at New York City’s IFC Center.

@jonnyabomb

- [THE BIG QUESTION] WHAT’S YOUR FAVORITE FEMALE ENSEMBLE IN MOVIES? - July 22, 2016

- [IN THEATERS NOW] THE BOY (2016) - January 24, 2016

- Cult Movie Mania Releases Lucio Fulci Limited Edition VHS Sets - January 5, 2016

Tags: 31 flavors of horror

No Comments