This article contains major spoilers for BONE.

In all honesty, it is hard to classify BONE as a “black” film, but it turns on themes of spoken and unspoken racism, serving as a more caustic, true to life corrective of well-meaning, but stilted, films like GUESS WHO’S COMING TO DINNER or IN THE HEAT OF THE NIGHT. More of a small ensemble piece than anything driven by one or two star performances, Larry Cohen’s feature directorial debut is a satire of racial tensions, sexual mores, and the corroding influence greed has on the soul. There is no sense of Cohen or the cast patting themselves on the backs, congratulating each other on how sensitive they are to the plight of African-Americans.

With that meaner, shockingly funny sensibility when it comes to tackling racism, BONE was a dangerous movie to release into the country at a time when people were still reeling from the ugly, violent end to the ’60s and the Vietnam War still raging. But great satire is often born of such volatile situations. Great satire is also not afraid to ruffle feathers and cross the line between good and bad taste as needed, sometimes offending, but never without purpose. If you haven’t yet figured it out, I consider BONE to be a great satire.

Bill (Andrew Duggan) is a luxury car dealer who lives in a large house in Beverly Hills. Hovering somewhere between fifty and sixty years of age, he appears to have it all: a pretty wife, a nice home, a successful business, wealth, and status. But all is not well with Bill, as Cohen shows us right from the beginning with a surreal nightmare sequence that points to buried guilt and anxiety.

Bernadette (Joyce Van Patten) seems like nothing more than a bored, spoiled Beverly Hills wife. She lounges by the pool, smirking as Bill grumbles about the lousy job that the pool cleaning service does. Her smirk grows as he calls the cleaning company and instantly folds as his righteous anger at the lackluster job they have done gives way to an awkward over-politeness and nothing being accomplished. As Bernadette passive-aggressively needles Bill, it becomes clear that the couple have engaged in the same petty behaviors toward each other over and over in their marriage. They do not talk to each other so much as they alternately snipe and grovel in an attempt to get their way.

Enter an unnamed Stranger (Yaphet Kotto) who appears in their backyard by the swimming pool. Yaphet Kotto has been in roughly a hundred films and TV shows, so we all know that he can look like a very imposing man when he so wishes. In BONE, he has his intimidation factor turned up to eleven. His amused expression gives off waves of aggression, he struts instead of walking, and he eyes Bill and Bernadette like a predator does its prey just before pouncing.

There is almost something mythical about the way the Stranger just appears in the yard. He does not make any attempt to sneak around. The yard is wide open, so Bill and Bernadette should have seen him coming, but they did not. He is just there, smiling like the Cheshire Cat, seemingly knowing a secret about the couple that they do not know about themselves.

For their part, Bill and Bernadette go into groveling mode. Bill half-heartedly hopes out loud that the Stranger is from the pool service and points out a rat trapped in the pool filter. Bernadette covers herself with a robe and inches closer to the telephone as the Stranger reaches into the filter, grabs the rat, breaks its neck, and chucks it out of the yard. He then offers to shake Bill’s hand as he informs him that he is there to rob them and—should the mood strike him—rape Bernadette.

And just like that, BONE jumps into uncomfortable territory that borders on racially offensive. Viewers that know nothing about Larry Cohen’s films might be inclined to stop watching. Not only does it seem like it’s going to be an unpleasant home invasion story, but the introductory scene for the Stranger could be seen as bordering on racist when you take into account that Bill and Bernadette are practically pissing themselves at his appearance and that he seems to count on his race to scare the hell out of them.

But if viewers give up on the film at that point, they would miss out on a twisty, surreal, and fearless look at race and class in America during the years immediately following the Civil Rights movement. Not only do Bill and Bernadette turn out to be complete frauds (they are actually in severe debt from living well beyond their means), but the Stranger has his own issues of confused identity as he is painfully aware of the forces of institutionalized racism and poverty that have exiled him to a life of crime, yet he enjoys his criminal lifestyle. When Bernadette tries to stand up to him early in the film’s loopy second act, he yells back, “I’m just a big, black buck doin’ what’s expected of him!” But even he does not seem convinced by this statement.

During a long dialogue scene between the Stranger and Bernadette, he lays out his confusions about how everything was supposed to change overnight. He complains about movies with interracial couples taking “the mystery” out of being with a white woman. He talks about how he had taken on the role given to him as the “big scary black man” before the Civil Rights movement, but now he was expected to give that role up. Most tellingly, he complains about better off liberal white people telling him times have changed and he doesn’t need to be a criminal any longer. All he has to do is take up a trade. To which he responds: “What trades? I only know how to do one thing.”

It becomes clearer as the film gallops through its first hour that the Stranger has never talked to anyone in this way before. It also becomes clear that Bernadette relishes the role of acting as his therapist and “helping” him. While the film to that point has scored plenty of uncomfortable laughs and taken some deserved shots at lip-service progressives, it also has done so in ways that lack tonal cohesion and that sometimes depend too much on Bernadette playing the white savior, helping the Stranger see himself in a new light.

Then a brilliant moment comes as the film transitions into its final act. After seducing the Stranger, Bernadette slips into fantasy mode. Through gauzy soft-focus, she sees the Stranger on top of her and says, “Oh, Bone. You’re just as I imagined you’d be.” Suddenly, everything becomes clear: the tonal leaps, the strange plot twists that seem to go nowhere, and the occasionally offensive narrative of a white woman helping out a scary black criminal who has a secret sensitive side. It all makes sense because the Stranger has been conjured by Bernadette to take her revenge on Bill for any number of sins he has committed against her during their marriage.

As an added bonus for Bernadette, the Stranger (who is not actually named “Bone”—he only goes by that name once Bernadette gives it to him) is not only there to get her out of her toxic marriage to Bill, but also to validate her. She gets to indulge in sexual fantasies ranging from rape to curing her lover’s erectile dysfunction. She gets a partner who is masculine and sensitive—the exact opposite of the pathetic and unappealing Bill. She gets to feel good about herself as a rich white woman who is doing something for a minority.

The joke in all of this is that the Stranger is Bernadette’s idea of a black man. Yes, he turns out to have several good traits as she alters him to fit her needs and wants, but her initial vision of him is as a criminal and a rapist who enjoys targeting white women. She even gives him a history that she takes from old newspaper accounts about a man who would break into homes to expose himself to women. In her mind, all black men are criminals.

Because of the way Cohen weaves reality into Bernadette’s fantasies, when re-watching BONE, it is easy to forget that the Stranger is a conjured being. Part of this is Kotto’s excellent performance, which gives his character a wounded humanity. He is alternately funny, charming, and frightening as Bernadette sees fit to change him. In the film’s unsettling final ten minutes, he has been fully transformed to a man who does not look out of place driving around Beverly Hills in a luxury car.

The confusion the Stranger feels over just who or what he is supposed to be is at the heart of the film in the brutal finale. It is never clear if Bernadette is aware that she created and controls the Stranger, but he seems to understand that his end purpose through all the changes is to kill Bill for her. When Bernadette loses her mind and snuffs out Bill on her own, the Stranger looks on in sadness that changes to disgust as he says, “Hey, that was supposed to be my job.” Bernadette gave him an identity and then stripped him of it, just like he had complained about with the changes expected of him after the Civil Rights movement. You have to wonder just how many times in the past Bernadette has conjured this poor being and put him through the wringer.

In a moment that mirrors his entrance, the Stranger simply disappears. Bernadette finishes smothering Bill, looks up, and discovers he is gone. In a series of jaggedly put-together takes, Bernadette then practices her story for the police, telling her version of events as Bill being attacked and murdered by “a big n*****.”

It is a sad moment that drives home the point of the movie: for all the social upheaval and laws passed in the ’60s, nothing much changed. There will always be people in this world who are racist, cruel, and greedy. It is up to every individual to try and be a better person and not expect society or the government or the courts to make people change what is in their hearts. Despite all her claims to the contrary, what is in Bernadette’s heart is very ugly, and the audience is forced to stop laughing.

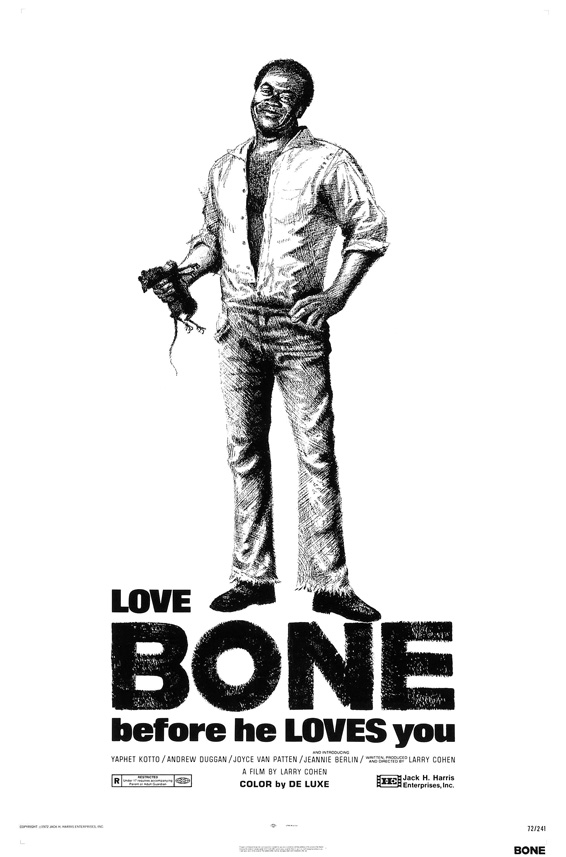

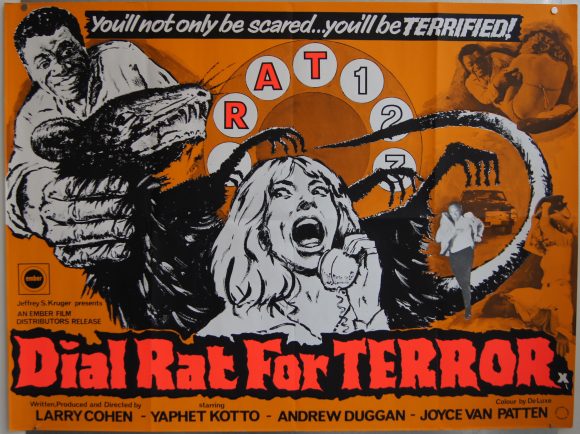

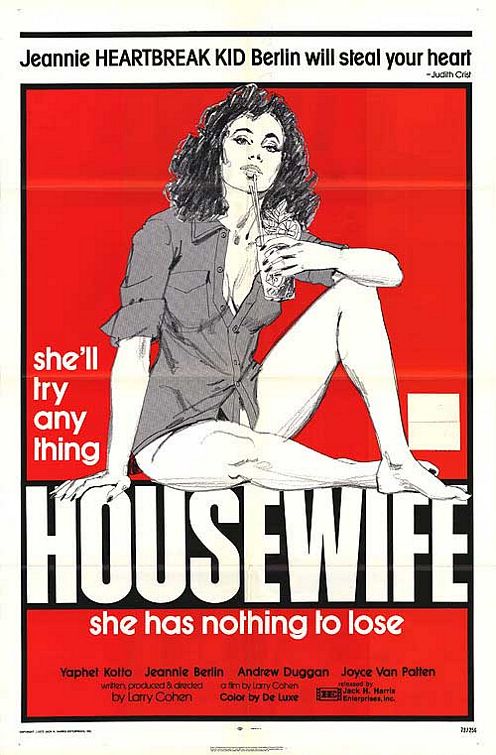

Unable to figure out how to market the film, the distributor sent it out under several titles (BONE, HOUSEWIFE, DIAL RAT FOR TERROR) and tried to sell it as everything from blaxploitation to a softcore film. Not surprisingly, it flopped under every title and in every genre. But BONE does not really belong to any set genre. That allows the film to play by its own rules, and that makes it just as urgent, scathing, and provocative today as it was when it was released.

Tags: Andrew Duggan, Beverly Hills, Black History Month, Black History Month Week, Brett Somers, George Folsey Jr., Jeannie Berlin, Joyce Van Patten, Larry Cohen, New World Pictures, Yaphet Kotto

No Comments