A few weeks ago, I found a copy of 10,000 Ways to Die at my local library. Written by filmmaker Alex Cox (REPO MAN, SID AND NANCY), the book serves as a collection of essays on Spaghetti Westerns released in Italy during the 1960’s and ‘70s. Each chapter represents a different year; each year consists of several key titles, such as the films of Sergio Leone or Sergio Corbucci. Cox combines his formal education in film criticism with his experience as a writer/director to discuss the progress of the genre as it became an international phenomenon. It’s an entertaining and educational book, or so I assumed at the time of check out. I’d never actually seen a Spaghetti Western.

I mention this now only in the interest of complete honesty. I never took any perverse pleasure in my ignorance of the Spaghetti Western; I never turned my nose up at conversations discussing ONCE UPON A TIME IN THE WEST or bragged that I’d only ever seen AMERICAN Westerns. I’d simply watched around the Spaghetti Western, seen the films they inspired and mistakenly come to the conclusion that I had no real interest in the genre. I’d seen Peckinpah’s THE WILD BUNCH and Hillcoat’s THE PROPOSITION; Eastwood’s UNFORGIVEN and James Mangold’s 3:10 TO YUMA. There were visual and musical elements that I had come to enjoy – I certainly appreciated the elements of the Spaghetti Western present in movies like RAVENOUS and most post-apocalyptic films – but the films I watched were too disparate, too varied to find the through-line of the genre.

To borrow a quote film theorist Alan O’Leary, there is an “iterative character” to genre film – a joy that comes from seeing the variations of a similar theme – that allows an appreciation for a genre to become self-sustaining over time. Without that character, I needed someone – a director, an actor, a writer – to serve as an infection vector for the Spaghetti Western. And thanks to my recent coverage of a Eurocrime festival at the Anthology Film Archives, I was able to find an actor that served as my toehold into the genre.

Enter Gian Maria Volonté.

Even if you are only familiar with Volonté’s work on A FISTFUL OF DOLLARS and FOR A FEW DOLLARS MORE, then you know of the man’s prodigious talent. Many actors from Spaghetti Westerns are inexorably linked to the genre. When westerns were viewed only as commercial trash, the actors were hired guns; when westerns became art, these men and women were elevated to the status of respected character actors. Volonté bucked this trend by being one of Italy’s brightest stars both before and after his work in westerns. He was the face of a new breed of Italian actors who eschewed classical form for authenticity. Volonté would receive international acclaim for his politically-driven films of the ‘70s and ‘80s but refuse to work in Hollywood due to the industry’s capitalist bent. A 2005 documentary about the actor titled UN ATTORE CONTRO – GIAN MARIA VOLONTÉ – included on the Blue Underground Blu-ray of A BULLET FOR THE GENERAL – describes Volonté as a figurehead for Italian actors as they fought for increased royalties on international distribution of Italian cinema.

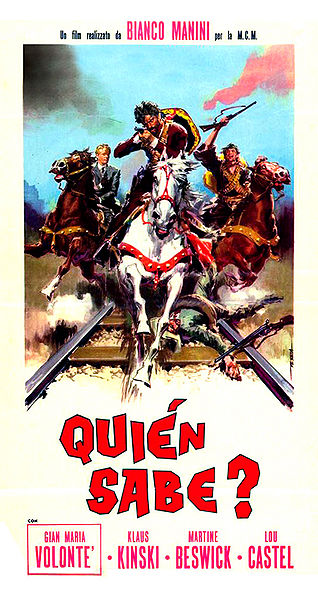

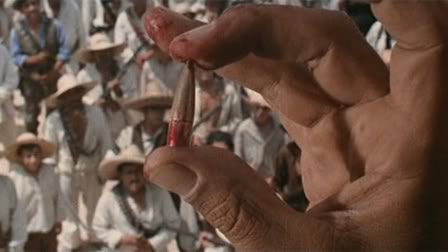

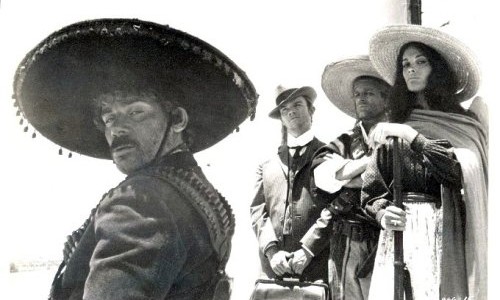

In A BULLET FOR THE GENERAL, Volonté plays El Chuncho, a bandit leader during the Mexican revolution who robs caravans and sells military rifles back to the rebel army. During the film’s opening attack on a stalled train, Chuncho meets Bill Tate (Lou Castel), an American gunslinger who assists Chuncho’s group in overpowering the train garrison and offers to join his cause. Before long, Tate is riding with Chuncho and his half-brother El Santo (Klaus Kinski) on raids against military outposts as they make their way across the Mexican countryside towards the general’s encampment.

Chuncho may be a simple man, but his relationship with Castel’s Tate is anything but. Cox writes about the overt gay bond between the two men, highlighting Chuncho’s infatuation with Tate and Tate’s desire to refine the uncultured bandito. Chuncho is confused by his loyalty to the young man he calls El Niño; at one point, Chuncho shoots one of his bandits for attacking Tate and must explain his decision to the rest of his gang.

Chuncho: Because Guapo wanted to kill the niño. And the niño is my friend.

Gang Member: Wasn’t Guapo your friend too?

Chuncho: (beat) Guapo is dead. Don’t worry about him.

As Chuncho delivers this last line, a smile breaks across Volonté’s face. This is the power of the actor’s performance. Volonté plays Chuncho as a character whose heart and whose mind are in constant conflict; when called upon to defend his beliefs, Volonté shows us a man on the verge of some inner realization who cannot – or will not – take that final step. Each time that Chuncho comes face-to-face with some unarticulated part of himself, he retreats into the advancement of technology. He shuts out further questions by fussing over a land baron’s automobile. He becomes obsessed with locating a machine gun among the weapons that he steals.

And while much of the gunplay in A BULLET FOR THE GENERAL is of the traditional clutch-and-fall variety, the film continues a trend of progressive violence set by A FISTFUL OF DOLLARS. In 10,000 Ways to Die, Alex Cox highlights several ways in which the Leone film pushed the boundaries of movie violence. As Cox writes, “It seems strange today, but one of the rules of self-censorship which Hollywood had adopted via the (Hays) Code was never to show a gun fired, and its victim fall, in the frame… Apparently, A FISTFUL OF DOLLARS was the first film to break this rule.” Cox highlights mercy killing – in particular, the scene where Joe shoots the wounded soldier in the hacienda – as an extension of this violence and an example of the new edge that westerns had adopted.

It’s easy to dismiss the brutality of A BULLET FOR THE GENERAL when every scene features a boisterous Gian Maria Volonté and mariachi music; look closely, though, and you’ll see an edge to the violence that caught me by surprise. In the opening sequence, a military train is forced to stop when it comes across a crucified officer in the middle of the railroad tracks. When Chuncho’s men overtake the train, executions and mercy-killings are so ubiquitous that director Damiano Damiani regularly places them in the background of his compositions. Subsequent scenes show soldiers being murdered at point-blank range under the guise of hospitality. Even El Santo gets into the action, punctuating the sign of the cross with grenades lobbed into a barracks. What makes these sequences so effective is Damiani’s pragmatic approach to the violence. People die, but not Chuncho, so who cares?

If you read Daily Grindhouse, you likely do not need to be sold on the idea of watching a Spaghetti Western. But to me, A BULLET FOR THE GENERAL was a revelation. By locking in on an actor whose methods I had come to hold in the highest regard, I was able to see the genre through fresh eyes. A BULLET FOR THE GENERAL has all the violence and beauty of its more well-known brethren with a central performance that runs circles around Nero and Nero. And it’s playing in glorious 35mm this week at the Anthology Film Archives in New York City as part of a Kinski retrospective. “See the film that undid thirty years of apathy towards westerns!” may not be the sexiest tagline of all time, but it serves its purpose. I may never have taken the plunge without Volonté and company to prompt me.

A BULLET FOR THE GENERAL is playing tonight, tomorrow, and next Saturday as part as the film series entitled “IF YOU MEET KLAUS KINSKI, PRAY FOR DEATH.” A Blu-Ray & DVD edition is available from Blue Underground.

— Matthew Monagle.

@LabSplice

- [THE BIG QUESTION] WHAT’S YOUR FAVORITE FEMALE ENSEMBLE IN MOVIES? - July 22, 2016

- [IN THEATERS NOW] THE BOY (2016) - January 24, 2016

- Cult Movie Mania Releases Lucio Fulci Limited Edition VHS Sets - January 5, 2016

Tags: "Spaghetti" Westerns, Alex Cox, Damiano Damiani, Gian Maria Volonté, Klaus Kinski, Lou Castel, Screenings, Sergio Corbucci, Sergio Leone, World Cinema

No Comments