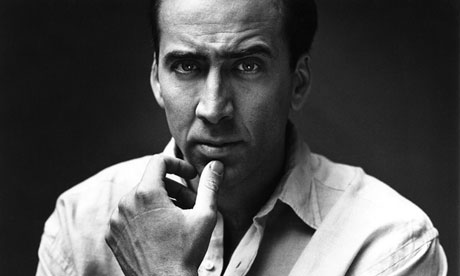

When you stop to think about it, Nicolas Cage becoming a huge movie star is one of the weirdest things that’s ever happened to American movies. And also, probably, one of the greatest.

It’s not that he isn’t a unique, unusual talent — very much the contrary — the oddness of his success is the monumental level of oddness he brings to the screen. Nic Cage is a maximum-wackadoo super-freak punk avant-garde weirdo. That is absolutely the makings of an all-time great character actor. It is very rarely the way you’d describe a genuine name-above-the-title movie star, which he in fact somehow is.

The first time I saw him was probably in his uncle Francis Ford Coppola’s intriguing B-side, PEGGY SUE GOT MARRIED — I’m not quite that old, but it used to run on HBO back when I was first starting to explore that channel. The film is a romantic drama, one of those baby-boomer nostalgia pieces that was big in the ’80s, and as such it was over my head when I saw it. The major thing I retained was that total weirdo playing Kathleen Turner’s high school sweetheart-turned-husband. Only 22 when the film was released, Cage plays the same character at two ages — teenager and middle-aged man.

Please note that this movie contained that performance and still it was not only well-reviewed, but a financial success. Again, I’m totally down with that, but let’s not pretend this isn’t bizarre and inexplicable. Cage plays that character in a way that suggests Bill S. Preston and Theodore Logan welded together by science, with a fair amount of Max Shreck’s Count Orlok thrown in for good measure. For a movie where fellow professional weirdo Kevin J. O’Connor is the alluring romantic figure, maybe it fits. I remember finding Cage’s sad-cartoon performance to be moving, somehow, when I first saw this film. Obviously there were plenty with the same reaction, since very quickly Cage picked up lead roles. By the next year, 1987, he was starring with Holly Hunter in the Coen Brothers’ RAISING ARIZONA. Still one of the highlights in the reel of all involved, Cage very intentionally played that role as Woody Woodpecker.

I’m just saying, this is atypical business for marquee movie stars. Even Marlon Brando was technically playing dreamboats and heartthrobs when he started throwing eccentricities into the mix. Cage was full-throttle wackadoo right out the gate.

The point is that, from the very outset of his career, Nicolas Cage was one of the very most experimental of character actors, which makes his rise to bankable lead all the stranger and more wonderful. This past weekend, the good people at the new Alamo Drafthouse in New York recognized andcelebrated the fiftieth year on earth for this unlikely movie hero with a four-film movie marathon. All four played to huge reactions to a gratifyingly packed house. Genuinely sorry you missed it, if you did. Seems everyone who was there has written about it, the way they say everyone who saw the Velvet Underground play live went on to form a band.

As an aperitif, take a look at all the Caged-up trailers that preceded each movie:

CITY OF ANGELS (1998)

THE ROCK (1996)

LEAVING LAS VEGAS (1995)

KISS OF DEATH (1995)

DRIVE ANGRY (2011)

[Read the Daily Grindhouse review!]

ADAPTATION (2002)

BRINGING OUT THE DEAD (1999)

WILD AT HEART (1990)

And now, your four feature attractions…

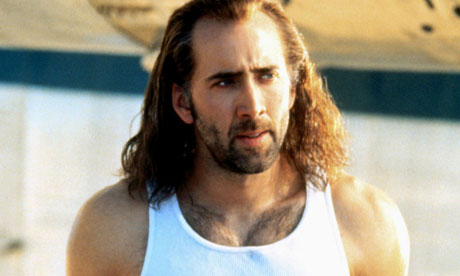

CON AIR (1997)

Nicolas Cage appeared in two massive action epics in 1997. One of them was helmed by one of the greatest action directors who has ever lived, and the other was directed by Simon West. CON AIR has many champions and I am one of them, but it isn’t exactly an auteurist work (I think veteran editor Chris Lebenzon and his team deserve a lot of credit for holding together a sometimes sloppily-shot film), unless of course a producer can be an auteur. This is one of the finer blockbusters of the Jerry Bruckheimer era, belonging toa genre I will call, for lack of a better term, “man-camp.” An appreciation for camp is generally attributed to gay audiences, but I’d argue there’s a kind of camp pitched to straight men, and this would be a prime example. When movie characters are writing messages in Sharpie on the bodies of dead men and then throwing the bodies out of airplanes, that kind of goes beyond your run-of-the-mill over-the-top action outlandishness.

Writer Scott Rosenberg clearly spared no restraint in naming the monstrous convicts in the film, and as usual the Bruckheimer machine stacked the deck with brilliant character actors. John Malkovich is the alpha-creep as Cyrus “The Virus.” Ving Rhames plays Diamond Dog, apparently a David Bowie fan. Steve Buscemi does a baby-Lecter thing as Garland Greene, “The Marietta Mangler.” Danny Trejo’s character is named Johnny 23, for extremely unpleasant reasons. Nick Chinlund plays stone killer Billy Bedlam. A very young Dave Chappelle, as Pinball, plays an early variation on his later Tyrone Biggums crackhead character. MC Gainey pretty much steals the show as the Nugent-esque Swamp Thing. Explosions play a major supporting role. Really, the explosions were snubbed by the 1997 Academy Awards.

Then there’s Nicolas Cage in CON AIR. Here we see one of the most unfortunate hairdos in a career that has seen a surplus of those. He looks kind of like Waingro, in a movie that actually already has Waingro in it! The Southern accent Cage uses as Cameron Poe, disgraced Army Ranger, is fairly unfortunate, but it’s hard not to suspect he knows that. In any other movie, Cameron Poe would be the weirdest character, but here Cage is playing the deep-blue hero so he is comparatively reined-in. That’s comparatively. You ought to see how much the other guys are mugging. Next to Malkovich and Rhames and Buscemi and Trejo and Gainey’s green Army helmet, Cage is only about 65% of what’s ridiculous about CON AIR, but make no mistake, he’s still ridiculous. His ridiculous performance is perfectly matched to the ridiculous tenor of what co-star John Cusack called at the time “an apocalyptic clusterfuck.” I would bet good money Cage is in on the joke far more often than his clip-culling YouTube mockers seem to assume. Speaking of betting, it’s worth noting that this is one of several Cage movies, along with HONEYMOON IN VEGAS and LEAVING LAS VEGAS, to come to its conclusion in Sin City. Any decent retrospective of an artist should notice patterns and themes as they emerge.

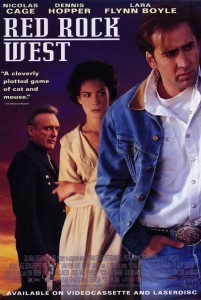

RED ROCK WEST (1992)

A country-Western neo-noir, RED ROCK WEST is one of the under-heralded gems of the 1990s. Director and co-writer John Dahl made a better-known cult hit the following year with THE LAST SEDUCTION, got a whole new following with 1998’s ROUNDERS, and has had a long and successful career directing television, but this early effort is a sterling example of clever, efficient storytelling which relies as much on character and visual cues as it does stylishness and bleak humor. Cage is at peak handsomeness in this film, for those who are interested in that aspect of an actor’s being, but what’s even more intriguing is how subdued he is, which was rare at the time and only got moreso as time went on. He plays the patsy in this noir set-up, with Lara Flynn Boyle as the femme fatale, the great J.T. Walsh as the weasel-eyed criminal mastermind, and Dennis Hopper as the… well, you’ll really have to see this movie to get the full picture. Let’s just say that Nicolas Cage was already an unhinged enough performer before he encountered one of the unhinged masters. Introducing Hopper to Cage would seem to be like dropping a gasoline truck into a volcano.

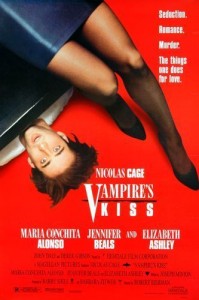

VAMPIRE’S KISS (1988)

All right. Let’s take a step back here for a second. We’re gonna need the distance. As much as most people know about VAMPIRE’S KISS, if they know anything, is that this is the movie in which Nicolas Cage ate a live cockroach. If that’s what you’ve heard, you have not been misled. But what if I told you that eating a live cockroach is only the fifty-third most bizarre thing Nicolas Cage does in VAMPIRE’S KISS? Written by Joseph Minion (AFTER HOURS) and directed by Robert Bierman, who was apparently up for Cronenberg’s job on THE FLY, the implications of VAMPIRE’S KISS are positively Kafka-esque. The best way I can describe it quickly would be to call it AMERICAN PSYCHO, only if Christian Bale’s character became convinced he was becoming a vampire. I’m really not sure what happens in the movie is meant to be taken at face value. Is he really becoming a vampire, or is he just really bored? I don’t know.

I do know that Cage’s performance in this film is almost literally deranged. In recent years, he has mentioned that his term for the acting style he has devised is “nouveau shamanic” — if that’s the case, then the spirit this particular shaman conjures most frequently is Max Schreck from NOSFERATU. German expressionism in general and that film in particular are massive influences upon the acting choices of Nicolas Cage. You can see it in the way Cage creeps into Kathleen Turner’s room at night in that aforementioned scene from PEGGY SUE GOT MARRIED. You can see it all the hell over VAMPIRE’S KISS. Not for nothing did Cage produce the 2000 film SHADOW OF THE VAMPIRE, which dramatizes the making of NOSFERATU, mischievously insinuating that Schreck played a vampire too well to be merely acting. In SHADOW OF THE VAMPIRE, Max Schreck is played by Willem Dafoe. One presumes this is because Nicolas Cage had already done it, in VAMPIRE’S KISS, although it should be specified that Cage’s Peter Loew is not a German, he’s a New Yorker who speaks in an effete, faux-British accent. Looking like a goofier version of Ryan Gosling, the young Cage is clearly being allowed to experiment. I don’t know much about Robert Bierman’s work but on the basis of this evidence, he was no Josef von Sternberg. In other words, he directs his actors on a loose leash. Peter Loew is an oddball creation, still one of Cage’s most manic, long before that extremely fake plastic bat ever flutters through the window.

There are three or four worlds Cage’s character occupies in VAMPIRE’S KISS — his brownstone apartment. which he brings his dates to and later haunts alone; the nightclub world, where he flirts with Kasi Lemmons and Jennifer Beals (the latter of whom he believes to be the vampire who sired him); the expensive office of his bemused therapist (Elizabeth Ashley); and his office at the literary agency where he tortures his sweet assistant, played sincerely by María Conchita Alonso. The workplace scenes are arguably the oddest of all, a reverse take on Bartleby The Scrivener wherein an insane boss torments his all-too-sane subordinate. Some of the broadest comedy in VAMPIRE’S KISS concerns Peter’s treatment of poor Alva, jumping on desks and widening his eyes like a wolf in a Tex Avery cartoon, terrifying her just because she can’t find a single contract he doesn’t need anyway. Even after the situation takes a surprisingly dark turn, the audience keeps laughing, though differently.

This was a fascinating movie to watch with an audience. I’m not sure I’m prepared to join the cult, because the tone is too inconsistent for me to be able to call this a good movie, but like CON AIR, VAMPIRE’S KISS is so aggressively itself that it’s worth a look.

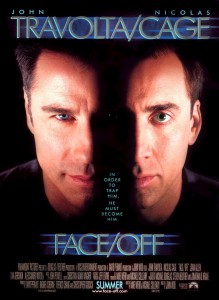

FACE/OFF (1997)

What kind of action fan are you? One way to tell is to consider which 1997 Nicolas Cage film you prefer: CON AIR is silly and trashy, the cinematic equivalent of a beach read — nothing wrong with it; those get the adrenaline surging. But FACE/OFF has two major virtues in its corner: Sincerity, which is more of an assumption on my part, and craft, which is a quantifiable absolute. Seeing FACE/OFF on the big screen, which I hadn’t done since I saw it three times during its theatrical release, I was struck by the mechanics of John Woo’s orchestration of action. It’s a routine rant coming from me, but action films have lost much with the trend towards hand-held camerawork — the sweeping motions of John Woo’s set-ups match and enhance the emotional moods of the piece. The critical cliché when it comes to John Woo’s films is that they are a “ballet of bullets” (or some such variation). It’s used a lot because it feels apt, but let’s not overlook the fact that these films can feel like opera — nowhere is that clearer than here, in his single best American film.

On a story level, FACE/OFF is packed with nearly as much absurdity as CON AIR. It’s set in a near-future where face transplants can be used for a federal agent to go undercover as a terrorist-for-hire and where maximum-security prisons run on magnets. It’s an out-sized movie in every way, with widescreen cinematography by Oliver Wood, a bombastic score from John Powell (maybe the best Hans Zimmer score not actually composed by Hans Zimmer), and, of course, two lead performances from two of the most shameless hams of the past fifty years of screen acting. I mean that in a good way: It’s good to be shameless. There’s too much shame these days. This movie is bold. The visuals create an epic visual space and the two stars manage to fill it. If Woo is a director of violent ballets, then he does well working with John Travolta, who is a dancer after all. And if FACE/OFF is modern opera, then it’s a natural home for Nicolas Cage, an actor who has no problem going big. In fact, he’s just waiting for the next available opportunity to do just that.

Here Cage plays the impossibly-named Castor Troy, a madman with a proclivity for explosions. He loves only two things: His computer-hacker brother Pollux, and grabbing lady-butts. (He grabs a lot of lady-butts in this movie. More than you may remember. And that seems to do it for him.) The opening scene of the movie shows Castor making an assassination attempt on Sean Archer (Travolta), the man who has been hounding him. The bullet rips through Archer and kills his young son, who was riding a merry-go-round with him. [Shouldn’t Castor have waited until Archer got off a moving carousel?] Archer lives, and six years later, after a pretty elaborate chase scene involving a plane — this movie begins the way many action movies, last year’s FAST & FURIOUS 6 included, end — he arrests Pollux and kills Castor (or so he thinks). But the brothers have set a ticking bomb to take out a square mile of populated Los Angeles real estate, so Archer submits to a pioneering face-transplant procedure so he can enter a maximum-security prison to get Pollux to reveal the bomb’s location.

In other words, for the first act of the movie Travolta plays the stalwart hero and Cage the deranged villain. Then Cage becomes the hero, but in the body of the villain. When Castor Troy comes out of his coma — in a scene very much like the Joker’s creation in Tim Burton’s BATMAN — he takes Archer’s body and torches the lab, and now Travolta is playing the villain, destroying his enemy’s life from the inside. He takes over Archer’s job and his family, and this movie goes to some pretty perverse places for a mainstream Hollywood blockbuster. Really, Cage gets the meatier role, especially since Travolta had already done the swaggering bad-guy thing for Woo in 1996’s BROKEN ARROW. Travolta has fun mimicking some of Cage’s more obvious mannerisms, but it’s Cage who gets to swing from the most drastic extremes, from the sociopathic and anarchistic maniac to the vulnerable, beleaguered, and cornered good-guy-on-the-run. Travolta is really good, but Cage is great.

Many people in the Drafthouse audience giggled every time the Archer family did their trademark gesture, of waving a hand over the face of a loved one — I can agree that this happens maybe three times too many, but I also think it’s key to both this film and to Cage’s career as a whole. I’m not sure if this idea was in the script or if John Woo himself came up with it. Maybe it was one of the actors. Audiences in 2014 laugh at such overt sentimentality and obvious symbolism, but I’d argue it comes about honestly — first of all, John Woo’s cultural background is Chinese, where even today such business might not be laughed away, and also, John Woo grew up on old-Hollywood musicals, where florid gestures indicate key character moments. If Nicolas Cage has such a moment in a John Woo film, it’s sincere. John Woo takes the emotion of an action film seriously, and Cage is rarely less than fully committed. That said, when Cage’s character in CON AIR is monomaniacally focused on a stuffed pink bunny which he means to give to a daughter he never met, it’s entirely played for laughs. When Simon West does sentimentality, it’s a gas. When John Woo does it, it’s from the heart.

The beauty of Nicolas Cage is that he means it both ways, in both cases.

— JON ZILLA.

- [THE BIG QUESTION] WHAT’S YOUR FAVORITE FEMALE ENSEMBLE IN MOVIES? - July 22, 2016

- [IN THEATERS NOW] THE BOY (2016) - January 24, 2016

- Cult Movie Mania Releases Lucio Fulci Limited Edition VHS Sets - January 5, 2016

Tags: Action Film, danny trejo, Dennis Hopper, Horror, J.T. Walsh, Jennifer Beals, John Cusack, John Dahl, John Malkovich, john travolta, john woo, Jon Abrams, Lara Flynn Boyle, Las Vegas, Los Angeles, María Conchita Alonso, New York, Nicolas Cage, Noir, Sci-Fi, Steve Buscemi, Texas, vampires, Ving Rhames

No Comments