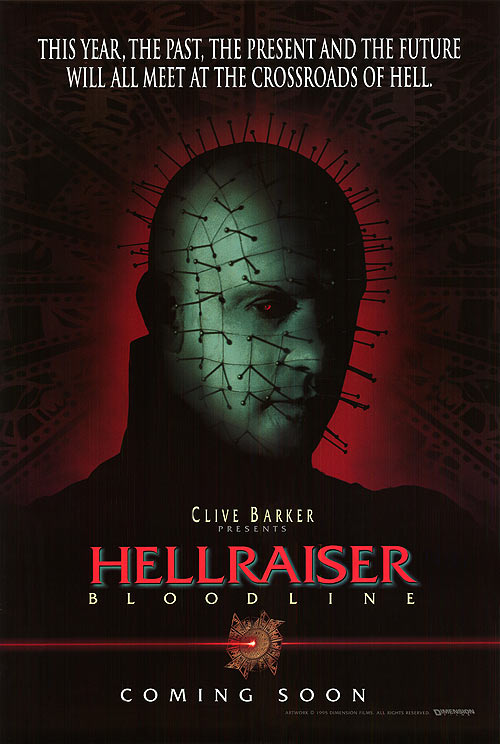

The second of the HELLRAISER (1987-2011) series to be released within the confines of Cinéma Dévoilé, HELLRAISER: BLOODLINE is the more oft ignored of the two sequels. Indeed, HELLRAISER III: HELL ON EARTH (1992) is the better film, and one which I look forward to taking you through at a later date, but I choose BLOODLINE as our first journey into Hell, because of how perfectly it demonstrates both the strengths and weaknesses of the Cinéma Dévoilé film.

Written by Peter Atkins, who also scripted HELLBOUND: HELLRAISER II (1988) and HELLRAISER III: HELL ON EARTH, the original script was considered to be a great piece of screenwriting that changed the focus of the series away from Pinhead and instead highlighted other cenobites while following a linear timeline that divided the action of the film through three different time periods: Victorian, Modern and Future. Production company, Dimension Films — then owned by Miramax (and now by The Weinstein Company, meaning it’s always been retained by at least one of the Weinstein brothers) — demanded a new cut of the film that introduced Pinhead earlier than the 110-minute initial cut (its existence at all a miracle, after a shoot from Hell that saw the first cinematographer and camera crew all replaced). The new cut required new footage shot, and director Kevin Yagher refused to do so, changing his credit into the dreaded “Alan Smithee” — the official pseudonym for directors looking to remove their name from a project. The new cut of the film is a disjointed version of the earlier script, now narrated through flashbacks from the year 2127 rather than told linearly; however, despite the negativity surrounding the film, it’s still an enjoyable — if slightly psychedelic — flirtation with the forces of Hell.

As the film opens, we’re introduced to Dr. Paul Merchant (played by Bruce Ramsay, who also plays his ancestors), alone aboard a space station, as he uses a robot to solve a puzzle box, the Lament Configuration. When a group of space police manage to break into the station and take Merchant prisoner, he agrees to explain the history of the Merchant family, the Lament Configuration, and his plan to destroy the cenobites, demons from hell, once and for all. We first travel back to 1796 France, where Phillip LeMarchand, toymaker, first creates the Lament Configuration, based on designs by Duc de L’Isle.

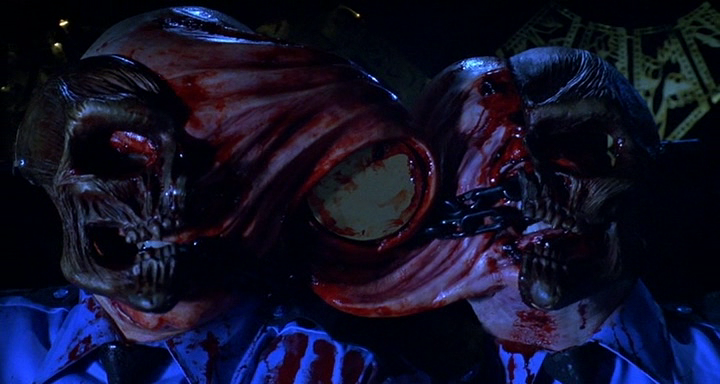

L’Isle, upon receiving the box, immediately sacrifices a woman to summon the demon Angelique, who takes the form of the peasant girl (played by Valentina Vargas). LeMarchand is killed, and told his bloodline is cursed. Next we’re taken to 1996, where we’re introduced to John Merchant, an architect that has designed a building with a striking similarity to the Lament Configuration. Angelique hears about the construction of the building and the architect that designed it, and she heads out in an attempt to destroy his bloodline. Inside the building, which seems to shift — doors appearing where should be none – Angelique tricks a horny man into opening the box and summoning Pinhead. Pinhead immediately starts to make more cenobites, eventually killing John Merchant, but the bloodline survives. We finally return to 2127 proper as the space police, with the help of Dr. Paul Merchant, must take on Pinhead and the cenobites from 1996 (funny he didn’t take the opportunity to create more in the 131 years since we last saw him) and put an end to the fateful battle the Merchant bloodline has fought for the last 331 years.

If the plot sounds complicated, that’s because it sure as shit is. It isn’t helped by the fact that decisions at times seem to come from nowhere and sections of the film have been entirely removed, causing even more confusion. But what it lacks in coherence, it makes up for with sense of psychedelic free-flowing thought that is reminiscent of a darker, cheaper version of VALERIE AND HER WEEK OF WONDERS (1970), a more fantastically disjointed timeline a là IRREVERSIBLE (2002), a horror version of the excess of BEYOND THE VALLEY OF THE DOLLS (1970), or a more coherent DELLAMORTE DELLAMORE (1994). High praise? Perhaps. But with all the films of Cinéma Dévoilé, we have to understand it as a film that is lacking in freedoms, as a film that is beaten into it’s moulding by the hands of the studio or by the lack of budget. Here we have a film that has taken such a bloody beating that it has been given to Alan Smithee.

What are we to make of Kevin Yagher’s decision to remove his name from the finished product? It’s understandable, on the one hand, that he didn’t want his name attached to the product after its changes, because they differed so greatly from the original image of the film that he worked hard to achieve. But what about his future as a director? Rather, has lack of a future as a director since HELLRAISER: BLOODLINE marks his first, last, only directed feature film — a state which I believe is a missed opportunity, given that BLOODLINE is a perfectly well-directed film that demonstrates an understanding of the medium. The problems of the film are mostly due to the editing, the actual direction of the piece is solid, working to craft a mood and deliver some visceral thrills. If anything, BLOODLINE being Yagher’s only feature demonstrates the perfect example of why an artist should stand by their work, even when it has faltered to live up their expectations.

Criminally underrated, HELLRASIER: BLOODLINES marked the last of the “classic” HELLRAISER films, the series taking a drastic turn in HELLRAISER: INFERNO (2000), a turn which we’ll explore on a future Cinéma Devoilé along with HELLRAISER III: HELL ON EARTH. But before we return to hell, we’ll be taking a detour into werewolf territory next week. See you there.

Tags: Adam Scott, Alan Smithee, Bob Weinstein, Bruce Ramsay, Cinema Of The Devoid, clive barker, Dimension Films, Doug Bradley, Hell, Hellraiser, Horror, Joe Chappelle, Kevin Yagher, Peter Atkins, Pinhead, Sequels, The Lament Configuration, Valentina Vargas

No Comments