There’s a certain breed of bad movie that has a look that tells you right off the bat that what you are about to watch is going to be a bad movie. You know the look. It’s a high digital gloss look, all blue tint gels that give indoor scenes an icy, desaturated look and blown out, radioactive whites that make light streaming in through a window look like an alien invasion is taking place outside. It’s an act of color correction designed to make a film look…bigger than it actually is, grander and more stylish than its means. It’s a look given to ultra-cheap movies (almost always genre fare) to make you think they cost more than they did. Only it has the opposite effect: it makes the movies look much that cheaper and low rent.

It’s not necessarily fair for a critic to judge a movie by its budget; a lot of great films have overcome monetary limitations and cruddy visuals to be great. But there’s something about the blue tint haze look that screams “bad movie.” It’s because the filmmakers care more about what it looks like on screen that what is happening on screen. There’s such an effort to make the film look glossier than its means that everyone involved forgets how to mine a compelling drama from the story in front of our eyes.

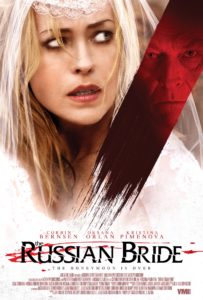

There may be exceptions to that rule — I haven’t seen any yet — but THE RUSSIAN BRIDE is certainly not it. It’s a modern day Gothic that tries to eke out as much production value as it can from Scripps Mansion, the Tudor-style manor where it was shot, bathing it all in that chilly cobalt glow. It’s meant to be a cry for the plight of mail order Russian brides, trafficked on the Internet for the benefit of rich, desperate misogynists. Oksana Orlan plays Nina, desperate to get her and her daughter Dasha (Kristina Pimenova) away from an abusive ex in her native Russia, who accepts an invitation to be the new wife of Karl Frederick (Corbin Bernsen), a wealthy widower in America. At first, things seem fine — Frederick, who’s been unable to recover after the death of his wife and son, is warm and welcoming to both Nina and Dasha, and the spectacular location is a monumental step up from the cramped apartment where they used to live. But secrets lie in the halls, and the longer Nina stays there the more she begins to fear for her and her daughter’s lives.

Writer/director Michael S. Ojeda tries to keep the suspense up about what or whether there is even indeed anything nefarious afoot at the Frederick homestead, but he drops the ball almost immediately. The casting of Bernsen is part of the problem. The actor can be a fine, if sometimes hammy, one, but he’s played enough sleazeballs, villains and bad guys throughout his career that just seeing him play the role of a mysterious rich guy only tips you off that he shouldn’t be trusted. Indeed, Ojeda does nothing to subvert the casting, but even without the metatextual element of Bernsen’s casting, the film is so uneven on the depiction of the character’s actions, that it’s made far too clear, far too early that things aren’t what they seem. Frederick vacillates clunkily and uneasily between kind and warm, and moody and secretive, that when Ojeda tips his hand far too early, the film’s mystery cannot ever hope to recover.

And the same is true with the rest of the film, as Ojeda introduces a snarling, potentially vicious pet dog (that never plays a part in the plot otherwise) and a pair of creepy hench-servants that are similarly unevenly portrayed. Then there’s the deus ex machina ghost, which shows up early, and almost hints that the film seems to be aiming for a throwback to the old Barbara Steele Gothics of ‘60s Italy — only for Ojeda to once again drop the ball on that listless, underdeveloped story strand.

None of this makes for a good movie, mind you, but it also isn’t necessarily fatal. THE RUSSIAN BRIDE has the blandly semi-competent vibe of a film that acts as film fest filler before limping out to provide the same service for VOD and streaming outlets. It’s merely…forgettable. It’s when the movie slides into its climax that it goes from nondescript to risible.

(From here on out: THERE BE SPOILERS.)

The act of snorting cocaine provides a sort of running motif throughout the film. Nina’s ex is a drug addict who is seen snorting a line immediately prior to demanding to see Dasha. As Nina is settling in, she walks in to find Karl snorting a line in his office, the first of her red flags that not all is right. The housekeeper reassures her that it is only used to numb the pain of his son’s death, not a serial problem. But here we have a woman desperate to make a new life for herself and her daughter accidentally stumbling from one problematic man to another, richer one with the same exact problem — the cycles of toxic relationships continued.

In the end, though, as she has been tortured and mutilated, her daughter in danger, drugged into a stupor, Nina falls face first into Karl’s pile of cocaine, accidentally snorting some. When she realizes that the cocaine is counteracting the drugging agent in her system, she snorts even more, becomes a crazed superwoman, gorily tearing through the house massacring all the bad people there who present a danger to her daughter.

And, yes, it is as silly as that sounds.

–Johnny Donaldson (@johnnydonaldson)

Tags: Cinepocalypse 2018, Corbin Bernsen, Gothic, Horror, Kristina Pimenova, Michael S. Ojeda, Oksana Orlan, The Russian Bride

No Comments