We smoked a lot of weed on the loading dock behind the video store I ran in West L. A. Most of the time, we were talking about how much we hated the customers, like the guy who made you clean every disc before he rented it, or the people who insisted on only watching full frame. Sometimes we talked about customers we liked. We were near the studios, so film people with professional experience came in all the time. They often knew so much, they would overwhelm you with information.

On occasion, these customers would share their excitement over a recent viewing. Sometimes, the same film would come up over and over all day long. One of these films was BATTLE ROYALE. People would come in and say ‘you haven’t seen BATTLE ROYALE? You have to watch it.’ For me, this was a terrible quandary. I knew if I didn’t watch the film relatively quickly, I would get so sick of people telling me to see it that I would take years to get around to it.

This was not the case with BATTLE ROYALE. I watched it right away and I liked it. So much so that I embarked on a quest to watch every film by director Kinji Fukasaku that I could get my hands on. Being in charge of the video store meant that pretty soon, we had a very extensive Fukasaku collection.

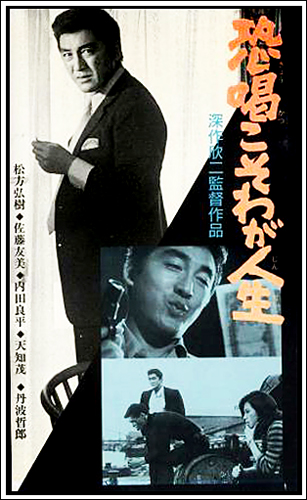

The first Fukasaku I saw after BATTLE ROYALE was BLACKMAIL IS MY LIFE, and it remains my favorite. Not to say that it doesn’t face some stiff competition. There’s GRAVEYARD OF HONOR, which was recommended to me by regular customer and all-time nice guy Ernest Dickerson as his favorite. I also became a fan of the THE YAKUZA PAPERS. I bought the black metal box of DVDs as soon as it came out, and have re-watched it a surprising number of times. I once put it on a muted television at a party, and it mesmerized the room. Finally there’s my second favorite, IF YOU WERE YOUNG: RAGE, about some five young guys buying a dump truck so they can start an independent hauling business.

Both BLACKMAIL and IF YOU WERE YOUNG express Fukasaku’s ideology quite clearly, but the latter does so more directly. In IF YOU WERE YOUNG, a group of young men are laid off from a terrible job in a factory. You know it’s terrible because Fukasaku shows a montage of shitty working conditions in Japan as the film opens. He even puts an income-to-education chart on screen to emphasize the tough situation facing the working class Japanese of this era.

In the film, Fukasaku employs abrupt flashbacks and a chaotic camera to emphasize the randomness of the forces arrayed against the characters. Also the cramped interiors and close-ups pin the characters in their surroundings. Their fate is inescapable.

The protagonists in IF YOU WERE YOUNG have the odds stacked against them, and are unequipped to deal with the setbacks that come their way. The consequences are devastating. Despite all this, the main character survives with optimism intact. He will continue to fight.

BLACKMAIL IS MY LIFE does not end so well. Maybe that’s why it is my favorite. I am a pessimist, and downbeat endings stick with me the most. Despite the doom of the story arc, the film has an upbeat energy and modern style which I love. It also focuses on the world of low-rent criminals, characters that I find fascinating.

There’s something else to why I like Fukasaku, an overarching theme to his work. He focuses on the failures and defeats of the failed and defeated. In interviews, Fukasaku often tells a story from his youth to explain his focus:

Fukasaku grew up during World War II, working in a munitions plant with his middle school classmates. Frequent Allied bombing had them ducking for their lives. They competed to hide under each other. Afterward, they buried their classmates in a field by the plant and got back to work.

Fukasaku explains that this background is why he reacted against the upbeat and positive stories he encountered at the movies, especially those types of stories that came out of Hollywood. He preferred darker European films to America’s studio output. He went on to construct his own cinema of setbacks and consequences, and this dynamic is evident throughout his films.

Fukasaku didn’t make his films in a vacuum. There are always practical limitations to film-making imposed by the production culture of the time. For Fukasaku, this meant speed. BLACKMAIL was one of four films he made in 1968. The film-makers adapted the screenplay in four days: an explanation, perhaps, for the episodic nature of the film.

Another limitation was soft censorship. At Tohei, where he worked early in his career, they insisted on happy endings. The good guy had to win, and the bad guy had to suffer. Around the time of BLACKMAIL, Fukasaku began working with Shochiku, a studio that didn’t have such a hard and fast rule. The executives didn’t mind if the good guys failed and the bad guy got away with it. This culture allowed Fukasaku to flourish.

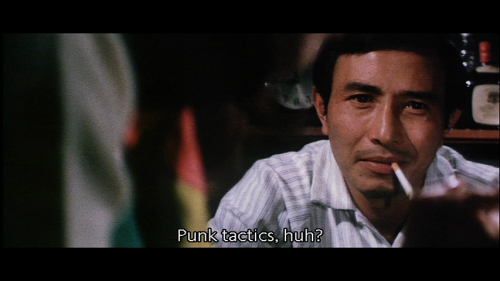

The story of BLACKMAIL is simple. It opens with the hero waking up in a squalid apartment, but behaving as if he were the king of the world. In the opening shots, his attitude does not match his surroundings, Often in BLACKMAIL, tight hand-held shots trap the characters in squalid surroundings where they have little room to breathe. The main character repeatedly breaks the fourth wall, desperate to define himself.

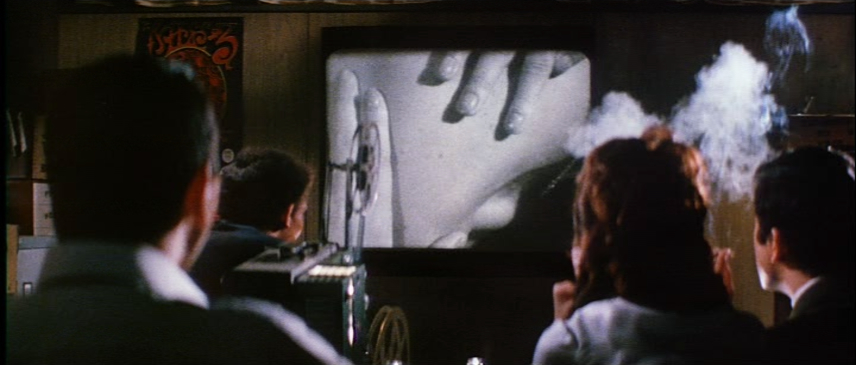

Fukasaku quickly introduces the crew with a freeze-frame of them at a meal in their restaurant hideout: a traditional place with few customers, almost abandoned. The crew members are all outcasts: a former yakuza, a mixed-race boxer named Zero, and a sexually liberated single girl; all connected by the desire to remain outsiders rather than falling in line and letting society define them. In one scene, the crew gloats over a crowd of salaried suckers and brags about stealing money from them.

The film then jumps back to how they all got started:The hero cleaning toilets and floors at a spa. Overhead shots of him cleaning, in contrast with his claims to greatness at the beginning. Women laugh and giggle around him as he mops. They are oblivious to him. He does not exist.

That night, he overhears two gangsters talking about selling fake booze at the high end club where our hero busses tables. He enlists the help of his friends in a blackmail gambit, and they threaten to expose the fake booze scheme. The gangsters pay them off, rather than deal with the hassle of shutting them up.

Just like that, a career in blackmail begins, and the four celebrate their success by racing bright red sports cars along the beach, and then running and playing in the surf. This part always reminds me of the camaraderie in films like BAND OF OUTSIDERS, and there are definite similarities between Godard and Fukasaku.

Fukasaku’s films are often compared to those of the French New Wave and Italian Neo-realism by writers who like to compare things. But above all, they are modern. The motions of the camera. Breaking the fourth wall. Flashbacks later cut together as montage. Brilliant stuff.

In the beach scene, the camera spins and whirls around the crew and shows their joy at their independence and the money their new identity as blackmailers will bring. The spinning, off-center camera on the beach celebrates the positive energy of the freewheeling youth. A freeze-frame ends the scene. The moment is over. Later in the film, Fukasaku deploys still images from the beach scene to communicate the motivations and the despair of the characters as their lives fall apart.

After several successful blackmail schemes, the hero gets involved with a high-end businessman who has a document he uses to blackmail the Prime Minister. This situation is based on true events in Japan. In typical Fukasaku fashion, he begins the film with a sarcastic title card that reads ‘not based on real events.’

Basically, the crew falls apart now that they’re in over their heads. The higher end of Japanese society closes ranks. This comes as no surprise. Throughout the film, Fukasaku jumps back and forth in time in a way that makes events seem fated and unavoidable. His celebratory and sometimes jarring camerawork both stresses the independence of the characters, while suggesting imminent disaster.

In IF YOU WERE YOUNG, one of the young men trying to by the truck is killed while working as a strike breaker. The camera shows him adrift in a sea of street-fighting bodies. The stumbling chaos of the camera matches that of the character as he slowly switches sides to protect the protestors, and gets murdered by the police for doing so.

One thing I’ve learned watching films is that I don’t know much about anything. Less even about Japan. Film and its language is evolving and complicated, and you can only go on what I’ve seen. By this measure, Fukasaku and his films are important, and BLACKMAIL is a fun one. You should watch it.

— IVAN INFANTE.

LOOKING FOR UNDERGROUND CULT MOVIES, DVDs, LIMITED VHS & OTHER COOL STUFF?

CHECK OUT THE DAILY GRINDHOUSE/CULT MOVIE MANIA STORE!

- [THE BIG QUESTION] WHAT’S YOUR FAVORITE FEMALE ENSEMBLE IN MOVIES? - July 22, 2016

- [IN THEATERS NOW] THE BOY (2016) - January 24, 2016

- Cult Movie Mania Releases Lucio Fulci Limited Edition VHS Sets - January 5, 2016

Tags: Crime, History, japan, Kinji Fukasaku, Noir

No Comments