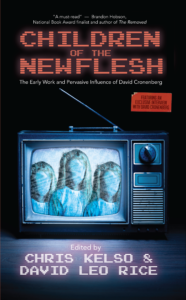

Children of the New Flesh, or “The Cronenbook” as I’ve affectionately come to call it, has seemed to be everywhere this past Summer. Though it wasn’t officially released (by the reliably highbrow grime peddlers at 11:11 Press) until June 30th, its rollout traveled so extensively along the same information side streets and back alleys I skulk around in my day-to-day internet life, that by the time I finally got a physical copy for review it already felt weighty and alive in my hands – teeming with vital hybridity, and freighted with a certain pressure to not only comment, but to add something new to its still-gestating conversation.

The writers involved, a few of whom I know in passing via those same seedy online gutters (and several more of whom I know by intimidating, intellectual reputation), are people I very much want to impress; people whose work, and if I’m being honest, whose recognition matters to me. I’ve spent the past (pauses to silently count backward, tearaway calendar pages fluttering across his bloodshot mind’s eye) six years writing, editing, and shamelessly pimping my own first novel, and while I’ve recently hit on some potentially game-changing success, The Cronenbook still feels like a golden opportunity to expand my fledgling network of literary colleagues, and perhaps, if handled just right, to finally join their ranks.

In preparation for this daunting task, over the course of the past three weeks I’ve eaten, slept, shat, and dreamt nothing but David Cronenberg. I watched all seven of the early short films around which this book is structured (Transfer (1966), From the Drain (1967), Stereo (1969), Crimes of the Future (1970), Secret Weapons (1972), The Lie Chair (1976), and The Italian Machine (1976), as well as a broad cross-section of his commercial filmography (VIDEODROME (1983), THE FLY (1986), DEAD RINGERS (1988), NAKED LUNCH (1991), Crash (1996), EXISTENZ (1999), A HISTORY OF VIOLENCE (2005), EASTERN PROMISES (2007), MAPS TO THE STARS (2014), and of course, also took in his latest feature, 2022’s CRIMES OF THE FUTURE. Naturally, as a longtime Cronenberg fan and erstwhile obsessive completist, I’d seen much of this material before (and have seen all of his films at least once – even his outstandingly generic 1979 racecar picture FAST COMPANY), but I wanted it all fresh; frothing at the front of my cerebral cortex, tripping my synapses, rewiring me into a conduit – nay, a Cronduit – of meaningful critical discourse.

All my prep pays immediate dividends as the book’s opening piece of fiction, Joe Koch’s “Invaginies,” reads like a tightly compacted ball of Cronenbergian runoff waste rendered ferociously corporeal by the ravages of its own journey toward sentience. Though officially nested under the Transfer section (Cronenberg’s goofy first short about a needy patient stalking his psychiatrist into the wilderness), this seething, first-person inhumanifesto makes at least passing reference to all seven shorts, as well as VIDEODROME and DEAD RINGERS, in taking a mass shooter’s aim at every social, medical, political, and biological system that’s led to its narrator’s incarceration in some harsh, institutional future. The promiscuity of Koch’s source material, and the vehemence of his delivery, conspire to give “Invaginies” the feel of both an honorific preamble to the rest of the book, and a “fuck the assignment” opening salvo against whatever order or logic one might have hoped to find there. Cronenberg, this piece viciously snarls from its feces-smeared psych-ward cell, has no answers for you. He is not here to warn you about the downfall of humanity, or even to commiserate in its dystopian descent. He is here to prepare you. To pop your pustular preconceptions and slurp you up into what’s already begun. To invade, infect, transmute, and rebuild you into something that’s ready. Something that could survive. Something that, someday, just might “fuck this building so hard it falls to the ground.”

I hadn’t planned to write about Koch’s piece first when I started – it’s not the actual beginning of the book, after all – but I went back and inserted the above paragraph in hopes of illustrating early on just how ideally designed Cronenberg’s work is to spawn new work of its own. If you think about his films too traditionally, they can begin to feel almost plotless – mimicking the illusionary, soaring-in-place momentum of a heavy drug trip, transcendent sexual encounter, or full-on psychotic episode. But if you can disengage from preexisting notions of what a film is meant to do and be, and get on his Malaysia-by-way-of-Pittsburgh wavelength, what becomes clear is that Cronenberg’s films are never plotless so much as they are resolutionless. Speculatively observational. They don’t render verdicts. They only present evidence. And even the ones that end in death never quite feel over, instead demanding the viewer go home and think on. Imagine forward. Poke and prod at the varicose implications left bubbling under the skin and burrowing inside the brain until something new inevitably takes shape, and hatches to the surface.

Oof, I think, internally chiding the cinephile pretensions of this last paragraph. I might be getting a little high on my own bug powder here. In my rush to show off my film nerd bonafides, I can already tell I’m trending dangerously toward an article that focuses entirely too much on Cronenberg’s films, rather than the Cronenbook they subsequently fertilized. That is the point, after all. It’s right there in the title. These writers are the children of Cronenberg’s new flesh, and their work here comprises an unwieldy, decentralized, and multifarious collection of his spiritual creative offspring – one that almost by necessity diffracts the readers’ attentions. You just might need compound eyes to take it all in I chuckle to myself, resolving to focus up and do better.

The From the Drain section is next (Cronenberg’s second short, wherein two veterans confront PTSD in a bathtub), and with it comes Gary J Shipley’s “Tendrils”, presented as one man’s nauseatingly clear-eyed and analytical inner monologue justifying murdering his family and burying them in the back yard. Shipley, whose work I know (and adore) through Apocalypse Party, Inside the Castle, and his own SCHISM Press, has taken up Cronenberg’s mantles (or, dare I pun, Mantles) of technobiological haruspicy and extreme body horror as dutifully as any writer working today, but “Tendrils” reminded me of nothing quite so much as Lars Von Trier’s ultraprofane, metaphorical serial killer autobiopic THE HOUSE THAT JACK BUILT. As with that Hellish, cinematic self-immolation, “Tendrils’” deranged protagonist might make a few halfhearted feints at regret, but he never allows for the possibility that his fate could have been otherwise. This was, to his confidently miscalculating mind, a thing that had to be done. All other roads are far in the rearview. And in following Shipley’s titular entities to their grasping, choking ends – tracing Cronenberg’s literalized metaphor out of the drain, out the door, and all the way across town to the throats of his loved ones – he stands as a similarly singular vision of homicidal depravity viewed through its own warped, fisheye lens.

Much better I think, patting myself on the back for this return to a more balanced assessment of the Cronenbook’s intertwining filmic and literary elements. And yet, even seven paragraphs deep, I’m still feeling a certain resistance from this work. Despite its endlessly furcated doors, it’s still hard to find a way in. How, I wonder, does one criticize criticism? How does one review a revue? In the past, especially when writing long-form pieces like this one, I’ve often relied on a personal, borderline confessional style wherein I tie whatever I’m covering into experiences from my own life – talk about not just what a book means, but what it means to me – and holding that blueprint firmly in mind, I decide to double back to the Cronenbook’s introductory thesis – “Long Live the Heroic Pervert” – courtesy of primary co-author David Leo Rice, a man who, via his genre-transmogrifying work for KERNPUNKT, Whiskey Tit, 11:11, and many other indie publishers of grungy renown, regularly writes things so effortlessly smart they make me want to cry.

Now here, I think, is something I can sink my teeth into. Something on which, if I might be so bold as to state it, I may even be uniquely suited to elaborate. As I delve into this mirifically insightful essay (which touches on many of the films mentioned above, but none moreso than Cronenberg ur-text VIDEODROME) and its proposal of a bold new archetype for the fast-destabilizing 21st century, I find myself thinking back on my own artistic journey up ‘til now, and my slimiest, sludgiest attempts to make something that would “break through,” a la the questing cynic Max Renn. His plight seems all too relevant to my current critical predicament, and it comforts me to reflect on his prurient pursuits, delving ever deeper into his own hermetic, voyeuristic/solipsistic narrative structure like a horny paladin forever in search of that perfect porn clip, only to meet again and again with more doors, into smaller spaces, containing only his priapic, panoptic self.

I too, after all, had birthed some outrageously grotesque and dirty shit across my nearly-39 years of earthbound scribbling, dating all the way back to the age of 9, and an in absentia obsession with the R-rated (and very off-limits) chestbursting ALIEN films (possibly inspired by the long scar running down my own chest, a remnant of neonatal surgery to correct a congenital heart defect) which led me to write and illustrate a disgustingly graphic bit of blood-n-chunks pre-internet fanfic (even bestowing its margins with a slew of self-congratulatory honors like “Little Grose Writers Award” and “Make Your Mom Barf of the Year Award”). Likewise, I can’t help but recall an epic erotic poem I composed by nightlight amid the hormonal blast furnace of puberty (no, you cannot read it). I remember how, for the want of even the softest of all imaginable smut, I fevered over those exquisitely pervy lines, revisiting and revising, night after night, as my flowering libido detailed increasingly elaborate desires for which I had zero real-world context. These youthful compulsions made for a strange disconnect – chemical and primal – the syntactic manifestations of my mind’s attempts to catch up to both the secrets of adulthood, and my own changing body – to close gaps, and engineer for myself all that which my still-small world held guarded under the lock and key of moral taboo.

Even as I grew older, and rendered some of my homegrown adult content flesh, the sacred, internal tug toward transgression would continue to inform my strongest work. Indeed, it has carried me all the way to today, to my debut novel Troll (coming Spring, 2023 from my degenerate benefactors at Whiskey Tit Books!), and in many ways, to this very article. I might even venture that through promoting myself, and engaging with the writing and indie publishing communities via Twitter, Goodreads, and various review sites like this one, I think, leaning back to indulge a self-satisfied surrender cobra in my ergonomic desk chair, that I have already effectively birthed my new, enlightened, heroically perverted self; the one Rice describes as “travel[ing] into the tech-mediated future… never certain that the confusion at the heart of all discourse can be solved, but willing to see it clearly as confusion, and to embrace it without fear or loathing.” I’d avoided smart tech and social media like the plague since their inception – a fearful, late-adopting luddite at every turn, ever grumbling about screen addiction and crowdsourced conformity – but now, surely, was my time – to get grommeted with a long-overdue BioPort, jack myself into a higher-functioning existence, and “pursue an internal obsession all the way to its gruesome finale.”

Advancing into the Stereo portion of the Cronenbook (Cronenberg’s first short feature, about a radical co-op of the mind), it is Evan Isoline’s experimental… something-or-other… it’s hard to even know how to describe the structure… that presents as my next logical progression. “Corpusplex” reads like a film treatment for a film format that hasn’t been invented yet – a 4-D sensory meld that draws readers one step closer to observation, observers one step closer to participation, and participants one step closer to the sublime. Isoline’s seamless, and eerily sonorous marriage of sci-fi neologism and deep-cut anatomical vocab (seriously, you might want a copy of Gray’s on hand for this one), makes for a thrillingly experiential vision of a machine that humans may have invented, but to which they are almost certainly now in thrall. Drawing on Stereo’s ideas of psychic communism and intralibidinal exploration, as well as our own current fears of an inescapably hyperconnected and overinformed media landscape where it is no longer possible to turn our devices (or ourselves) off, Isoline paints a vibrating, reverberating, phase-shifting portrait of our unnerving, innerving, (perhaps even, ubernerving) transhumanist future.

I’ve felt the power of this nascent collective consciousness over the past two years, as I trepidatiously offered more and more of myself up to the internet for appraisal, and found kind words and encouragement steadily flowing back in. I could see the good in it. No question. And yet, my hardwired mistrust of hivemind social engineering (blame… shit, the list is endless: Orwell? The Borg? The Bible? THE MATRIX? Take your pick) still has me reluctant to trust my newfound success. And though I haven’t shared my darkest misgivings with anyone as of yet (for fear that they would either mark me as a nutcluster neurotic, paranoid beyond all reason, or else worse, that they would be summarily and definitively confirmed beyond all doubt), the truth is I’ve been slipping lately. Questioning the integrity of my reality. I still often fantasize about that “bygone paradigm of ‘identifying the game’ as a means of breaking out of it” even while fully understanding that any form of simulation hypothesis “turns trite, not because it isn’t possible, but because even if it were true, it wouldn’t activate any meaningful recourse.” I struggle with this shit constantly. I long for higher meanings. Conspiracies. Deprogrammings. Apocalypses. Far less the ingenious, inside-outsider heroic pervert figure from Rice’s essay, it is rather the hopelessly naive looper he so eloquently derides as “reenacting an old war to keep from fighting a new one” – with whom I most readily identify; the one still fruitlessly searching for truth in a world where “we’re actually starting to doubt whether anything at all is true, and even whether anything could be.”

I stare down at The Cronenbook for a moment, overwhelmed by a sense that the faceless beings populating its cover are somehow staring back at me despite their absent eyes. What if, I wonder, questioning whether any of this is any good, or if I’m just garrulously jerking off on the work of my betters, I’m not the heroic pervert at all? What if I’m not even capable of nurturing him inside myself? What if I am, in fact, forever doomed to bang my head against walls of words and screens until, just like Max Renn, I can bear it no more? (It strikes me that this is, at least in part, even what my novel is about: a man repeatedly butting up against his own narrow understanding of himself and the world around him, and utterly failing to transcend).

Banishing these dark thoughts with a shudder, at least for now, I decide to press on to the Cronenbook’s other co-lead, Chris Kelso, and his trippy, cosmic horror fable “Contiguity to Annihilation”, the centerpiece of the Secret Weapons chapter (Cronenberg’s zany hot take on a coming North American civil war). Interlacing a more traditional, third-person narrative with snippets from fictional magazine interviews, Kelso traces the aural history of a musician on an all-consuming hunt for a literal new sound. One half of Soul Tragedy (to my imagination’s ear, a post-industrial electro-noise act), Marina has fled both her longtime partner, and her native Germany, in pursuit of “a field recording of the unheard pitch, the tunings of evil.” This rumored frequency has drawn her to a prefabricated American hamlet – creepily patterned after the architecture of her homeland – where everything feels a little bit unreal, if only by virtue of how hard it’s trying not to. Despite the town’s bizarre, set-dressing storefronts, and banally menacing denizens, Marina’s refusal to be warned off her search – her determination to trip the vantablack fantastic – sucks her into direct conversation with the yawping mouth of oblivion. And after but a brief, devastating snatch of her sonic holy grail from beyond the “endless pseudo-present” discussed in Rice’s opening essay (to my imagination’s ear, something like a detuned SunnO))) improvising inside Pauline Oliveros’s cistern) she discovers that, no matter how ready she believed herself to be, to actually be ready for the thing you want most in the world is but a crippling psychological and philosophical impossibility.

Holy shit is this what I’m doing? I wonder inside the increasingly tinnitusy echo chambers of my skull. Pretending to be readying myself for some magically-thought-out future of happiness and success, while actually just treading water in an infinity cove phishtank of bots and scams in search of something quantifiably unfindable? What’s going to happen to me, once I finally get what I want? What’s going to happen after that? And after that? And after that…

As if sensing my panic and responding accordingly, the Cronenbook all but flips of its own accord, Necronomicon-style, to “Death and Deceit in The Lie Chair”, a heart-piercing essay from the inimitable Charlene Elsby (the cover of whose last novel, Musos, incidentally, is a pretty good representation of what I imagine Kelso’s noisome void monster to look like). Elsby, in probably the sole incidence of anyone ever invoking Plato, Nietzsche, and Simone Weil in analyzing the short-lived, gloriously 70’s Canadian anthology series Peep Show (of which Cronenberg’s The Lie Chair was one of only 16 episodes), makes a hilariously bleak case for the hopelessness of most all hope. Using the story’s mildly clunky time-loop/ghost-possession framework as a jumping off point, Elsby outlines with crushing exactitude the paradox by which humans can never truly be satisfied, as their desires are bound inextricably up with a future that doesn’t actually exist. “We can imagine that anything happened when it didn’t” she surmises, “and we can imagine that anything will happen, when it won’t. But whenever we do so, we implicitly acknowledge that the temporal distance between our circumstance and that of the content of our imagination is what allows for these manipulations of reality” (ie – short of lying to ourselves, we can never have what we want, because we can only want what we don’t have). Making her case in a scant seven pages, Elsby approaches this decidedly dreary conjecture with a que sera good humor (another hallmark of the heroic pervert) concluding that, much like the quasi-spectral couple at the heart of the story, left with only self-deception and death as viable options, we could all be forgiven for living a few lies to get through our tiresome, repetitive days.

But then again… Max Renn chose door number two.

I stand up and begin to pace. I consider taking a walk, despite the pins-and-needles heaviness afflicting my sedentary legs. Maybe around the block, just for some fresh air. Maybe to the corner store for a pack of smokes (sitting is the new smoking, after all). Maybe to nowhere in particular, with no plan to come back. Dammit Charlene, I think, silently cursing the CLASH Books superstar, this is not what I need right now! My chest and genitals warm with the same febrile itch that prompted those childhood stabs at transgressive self-enlightenment, I summon all my remaining creative energies and return to my desk, determined “to embrace this coming age as a bloody and erotic spectacle, hilarious and nauseating at once, rather than as a series of slick consumer options wrapped in platitudes that barely conceal [my] raw terror” – as only the heroic pervert can, and must do. I will crack this assignment I think, or my own spine at the brainstem. Whichever comes first.

In classic Cronenbergian (and what I imagine we’ll all refer to someday as Leo-Riceian) fashion, Children of the New Flesh is essentially bookended by works to which its prolific co-curator applied his hand. Both his short story Re: Queen of Ashes (which closes out the section on Cronenberg’s sly, fetishism satire The Italian Machine) and Joseph Vogl’s mindblowing essay On VIDEODROME and the Paradox of Unmediated Revelation (which Rice translated from its original German), examine ideas of boundless repetition, regeneration, and rebirth within the isotropic sphere of new (if not all) visual media. Our “I”s have gotten bigger than our stomachs, Vogl seems to proclaim in explaining the dislocation and stratification of Max Renn’s locus of selfhood amid VIDEODROME’s apocalyptic narrative of endless rooms and bottomless screens. And furthermore, if we accede to his observation that the film’s script mimics the limniscate structure of a Mobius Strip, it undoubtedly follows that Rice’s own work – with Re: Queen of Ashes as a prime example – can often take on the dimensionless form of a Klein bottle, perpetually contracting and expanding, swallowing itself up only to miraculously bloom outward again from within; a smooth-walled living labyrinth tirelessly following its own Ariadne umbilical cord. As his story concludes, its twin narrators meeting in the middle of their static-filled box, their lifelong dialectic over the true intentions of simulacral omniartist Petra Mance at last synthesized to a standstill, I suddenly see it all, and alone in my darkened house, I loose a savage scream.

My brain is splitting at the sulci. My ego is barreling toward an auto/erotic crash. I’m done for. Bone dry. I’ve got nothing left to say, and I still don’t know if I’ve said anything at all. Not one interesting thing about this pulsating, pupating, parasitic book. I’ve long worried about the manner in which the internet’s constantly churning nexus of criticism and analysis (and my self-loathing complicity in it) might actually be contributing to the destabilized world in which we now swim daily – the way ideas and opinions have supplanted tangible facts, such that nearly everything truly can mean anything we want, provided we want it badly enough (and loudly show our shoddy work). It’s all right there in VIDEODROME. Cronenberg saw it coming 40 years ago! But more than all that even, I’m now questioning whether my motives for writing about it – Hell, for writing about anything – are even remotely pure. I’ve known I wanted to be a writer since I was in kindergarten, I remind myself behind quickening, ragged breath. But what exactly does that mean? What is it that I actually want? Acceptance? Validation? Respect? Fame? Love? Why am I looking for these things among strangers? In the vasts of the cyberveldt? Why the Hell do I care so much!?

I scurry over to my feeds, furiously scrolling through my 1,000+ Followings for some sign that any of the Cronenbook’s authors are actually real, but am met with only that all-pervasive, 21st century sense of the uncanny. That I’m being both watched, and projected. Both listened to, and repeated back at myself. Both consumed, and regurgitated. What if this whole fucking site is just some kind of alien observation plexus, or AI mirror interface? What if every person I’ve met on here is nothing more than a Magic Theatre reflection of the shards of my own shattered psyche? My name is David, after all, just like the book’s subject, and co-author (and my brother’s name is Chris!) (My dad’s name is Gary!!). What proof did I really have? Where were any of them now? Were they watching me from afar? Had I invented them all? Coded them to life from the whole cloth of my imagination? I’m holding The Cronenbook in my hand – their presumptive flesh rendered word in haptic paper and ink. Isn’t that evidence enough? I wonder, even while noticing that Rice’s squiggly note and signature on the title page looks less like human handwriting than the mimetic scrawl of a pen in the grip of a tentacle.

The harder I try to look away, the more connections I see; between myself and my online associates; between their various pieces for the Cronenbook and my own life; between the Cronenbook and me. But it’s a closed loop. I’m on the outside looking in, and thanks to this article, the inside looking out as well, simultaneously tilting at Kelso’s incomprehensible sound, and trapped in Rice’s all-pervading art installation. But never once – not for a moment – breaking through to meet myself in the middle. Had I been too earnest? my exhausted psyche wails. Too obsequious?! Asked too many favors?!? Used too many exclamation points!?!? Was my own book’s long-sought publication doomed to leave me disappointed, always chasing the future amid this interminable present? Was my desperation to “break through” palpable, even amongst the shared ether connecting tens of billions of screens? Was there truly no escape, and no outside to escape to?

“Tell me the truth” I demand aloud, and of myself, as there’s no one else and possibly never has been. “Am I still in the game?”

Sweating profusely and on the verge of delirium, I doff my shirt, open up my bootleg torrent of VIDEODROME and hit play. There has to be something I’m missing. Something they missed. All of them. All of us. Some aspect of the veiny, smoking gun at the center of Cronenberg’s oeuvre that will reel me back from the abyss and make this article sing.

Maybe something about the courage required to be a public-facing artist – to push past the impersonal remove of the screen, merge the real with the representational, and abandon your own claim to objectivity in the name of allowing your work to be a subject for others?

“Grow up” I mutter, slapping myself sharply across the face before lowering my hand to finger the measure of my long thoracic scar.

What about the idea that artists, on some level, need conspiracy theories in order to believe art is worth creating; need to believe that somehow, somewhere, someone has enough control over the world that their art could potentially find its way into their hands, and make a difference in how they exercise it?

“No, you fucking baby, that’s still not it!” I nearly shout, jerking open my desk drawer and retrieving an old boxcutter nicked from my indescribably mundane day job.

Maybe I just circle back to my earlier claim – the one about being “uniquely suited” to elaborate on the Heroic Pervert conceit – and admit that, despite my best attempts, I am in fact not “uniquely suited” to anything. That nobody is. That there are somehow both not enough of us, and too many of us, for anyone to be truly “uniquely suited” to anything anymore.

“Never,” I say, and drag the blade hard down my middle – sternum to stamen, as it were – before prying apart my chest cavity with both hands, and plunging the Cronenbook deep inside. I can feel it growing fleshy, drawing breath, wriggling beneath my ribcage and nestling amongst my organs before it gets to work tattooing them with quotes from Rice’s and Kelso’s interviews with the man himself. “I don’t have a vision” is carved into my spleen. “Live in the present” gets etched across my right lung. “I just wrote some stuff and what came out is what came out” stitches itself along my large intestine. “There is no sacredness” is a brand upon my stomach. “I am all the characters” marks my murmuring heart.

My fingers web and elongate outward, their newly suckered tips sealing tight against the home keys of my laptop (which itself has sprouted an insectoid abdomen and carapace of flaky, translucent wings). Iron axle rods and stainless steel specula puncture my limbs, erupting forth toward epidermal freedom until my thighs and biceps are bulging, vascular piles of metal and meat; wire and sinew. I feel my sex organs engorging in my lap, but in no way because I am aroused. My testicles swell to resemble sodden, ochre beanbag chairs, bursting what remains of my pants as my member flops over top like a bloated lamprey corpse. The entirety of my sexual apparatus continues to intumesce, pushing my legs out to either side until my pelvis cracks flat, and cramming itself flush to the furthest corners of my desk’s kneehole; fusing spongy soft wood and lacquered woodgrain into permanent, penis captivus intercourse.

My eyes have remained glued to VIDEODROME throughout my hideous dysmorphation, using it as a focus object while gritting through my self-birth pains, but now the familiar images onscreen are warping wide and colloidal, and the ominous score bends and oscillates like a whistling breeze blown directly across my brain; in one ear and out the other. My eye sockets, auditory canals, and already slackened mouth all begin to invaginate, their long-defined boundaries – my lips, lids, and auricles – peeling back and spreading outward, reclaiming my face and pate until my head is little more than five gaping orifices separated by the thinnest margins of maxillofacial skin (my nose remains centered and unaffected, save that it is now and forever beholden to the organic stench of my insides).

I don’t hurt, exactly, so much as I feel everything new, and ten-thousandfold, which I imagine will prove its own kind of hurting soon enough. I watch Max Renn hail the new flesh and put out his own lights, half-expecting my own new omnisensory dome to go dark along with him. But no. The movie is over, and I remain. Is this what I wanted? I wonder, as my chest slowly sutures up of its own accord, reversing course like a haunted zipper fly; the Cronenbook planted indelibly inside me; the scar that’s divided me in half my entire life now smooth to the touch – completely, undetectably healed. Are they all going to see me now?

-Dave Fitzgerald

I’m one of the authors in the book and, eh…I’m real. I think. 🙂