As Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau’s 1922 classic NOSFERATU: A SYMPHONY OF HORROR (German: Nosferatu – Eine Symphonie des Grauens) marks the 100th anniversary of its March 2022 premiere, we’re often made aware of the film’s travails with Florence Balcombe, Bram Stoker’s widow, as Murnau’s team hadn’t cleared any adaptation rights. Although first unaware of the German production, she received an anonymously mailed letter including a handbill from the film’s premiere at the Berlin Zoological Garden, declaring the film “freely adapted from Bram Stoker’s Dracula.” Although she was unable to collect money from the production company, Prana Film, who declared bankruptcy to avoid any payment to the widow, after a few years of legal pursuit, in 1925, she was finally able to win a ruling stating that all prints and negatives should be destroyed.

Fortunately for the world, a few prints did avoid this fate, and in 1929 the first screenings of Murnau’s dark classic in America took place in Detroit and New York City.

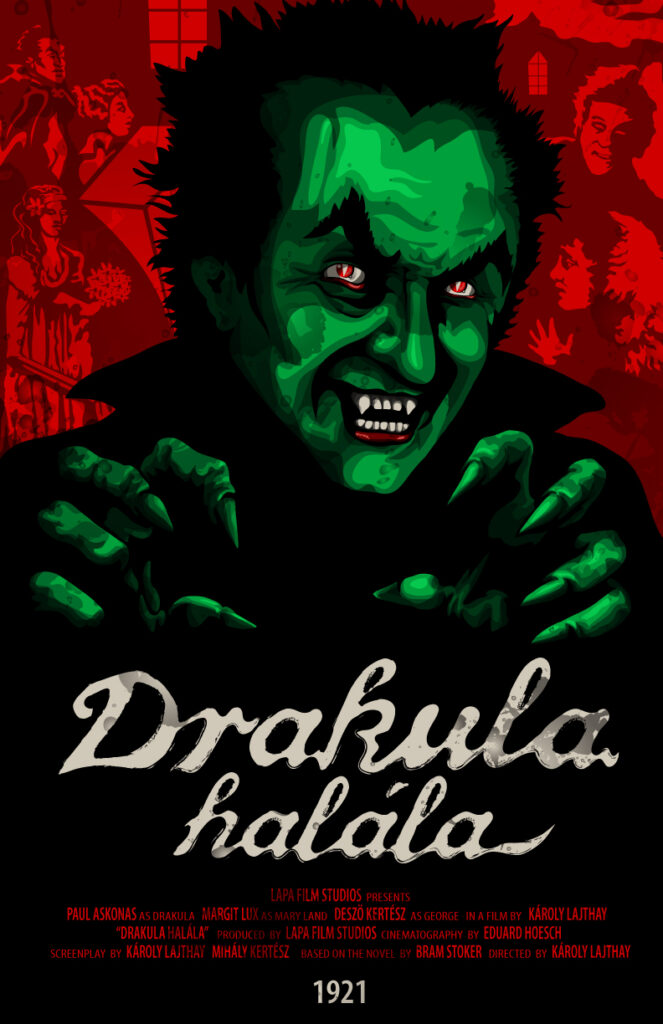

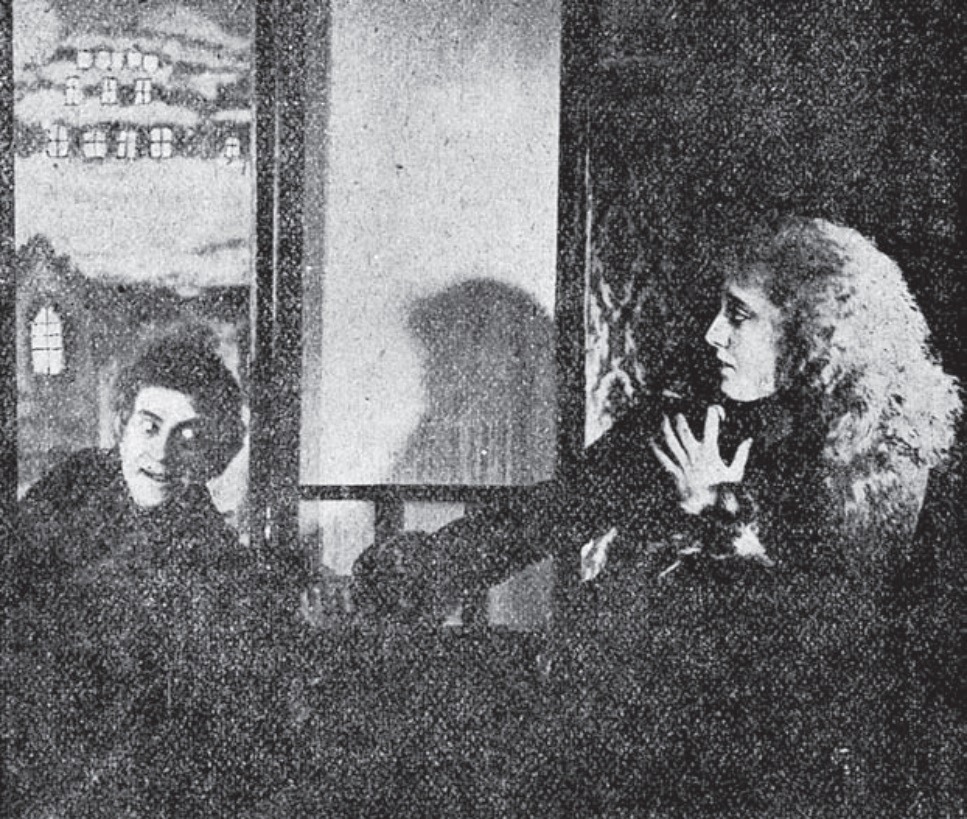

Less fortunate is the story of the very first film adaptation of a story of Dracula the vampire, albeit quite differently told, In the form of the previous year’s production of the Hungarian film DRAKULA HALÁLA (DRACULA’S DEATH), directed by Károly Lajthay, and starring Austrian-Hungarian actor Paul Askonas in the title role. One of the very few currently known images of the performer in the first Dracula onscreen conjures just as much enticing mystery as another lost silent, London After Midnight. With the character’s face rippled with madness, we can only imagine the horrors that gripped the audience when the film was finally released after Nosferatu’s great success. Though Mr. Askonas rose to greater fame later in his career, notably in Robert Wiene’s THE HANDS OF ORLAC (1924), alongside Conrad Veidt, his earlier role of Dracula is currently lost to the winds of time. Robert Wiene is of course widely known as the director of the even earlier surviving classic, THE CABINET OF DR. CALIGARI (1920). Askonas was well-versed in darker tales, having performed the role of Svengali in 1912’s TRIBLY (THREE TALES OF TERROR).

While the Library of Congress notes that as much as 75% of the earliest motion pictures are painfully lost, that number is even larger in Hungary where films rarely made it out of the country, and the advent of sound rendered earlier works obsolete. As much as 93% of Hungary’s early film work is just… gone.

DRAKULA HALÁLA’s director was quite notable when he took the reins of the first adaptation of Stoker’s character, having performed as an actor in several films including THE SEVERED HAND (1920) (another lost film, not listed at IMDB). Apparently enlisting the writing services of none other than Mihály Kertész (CASABLANCA director Michael Curtiz’s original Hungarian name), and actress Lene Myl, Karoly first called the film “Dracula” in an interview where he also mentioned Kertész’s involvement, though this is not mentioned anywhere else. As it is today, only Károly’s name can be directly attributed to the film’s script.

As Hungary’s film production changed due to the 1917 film-import ban which ensured Hungarian films a place in theaters, and resulted in the large Corvin film studios. Hungarian directors had been producing films in Vienna, and for larger studio work returned to Hungary to use the larger studio. By 1919 the film import ban was rescinded, resulting in a flooding of imported films, and the Hungarian film industry lessened its output. DRACULA’S DEATH, filmed in 1920, was part of this demise, and the film was only ever recorded as being presented in Hungary and Vienna, though after the success of NOSFERATU. DRACULA’S DEATH was not screened for the public until 1923, well in the shadow of Murnau’s work.

Rather than adapting Stoker’s novel, DRACULA’S DEATH was an original story that featured the title character as a distressed creature, or possibly yet another patient, in a mental asylum, with a poor seamstress named Mary who spends a night recuperating in the manse after the death of her father. The lead of Mary was played by Hungarian actress Margit Lux, whose credits include other titles possibly promising fear and dread, THE DEVIL (1918) and THE NIGHTMARE (1921). Similar titles also enfold the title star Paul Askonas, THREE TALES OF TERROR (1912) and THE HANDS OF ORLAC (1924).

As the film itself remains lost to time, László Tamasfi’s dedicated research brings to light much more than we could possibly know from just a few stills. In his slim volume he manages to thicken the plot with details only available to a Hungarian speaker. A more notable section includes a set visit to the Corvin Studios in Budapest, recorded by a writer in a 1921 edition of Szinhaz és Mozi (Theatre and Cinema). His description of the one scene of the wedding alone leaves the brain’s mouth watering over what this film may have looked like when it descended upon Hungary and Austria on first release.

“Dracula’s wedding gives a taste of the film’s energy. A huge room, marble all the way around, with a dark hallway at the center which appears to stretch forever.”

Already in Tamasfi’s translation our appetites for the dark lord are aptly whet. “It’s night time. You can hear the sounds of all kinds of animals yipping and squirming, and then a door opens in the middle, and beautiful women come to greet him, all in dreamy clothing, these are Dracula’s current wives. But now he’s awaiting his new bride, the most beautiful, the most desired, the one that he moved heaven and earth for…”

Fortunately for today’s readers of film history, Tamasfi is not happy just to accept a few lines here and there, or poorly quoting internet sites, which themselves are unvetted and poorly researched. Tamasfi provides every bit of information he could possibly find in his time poring over Hungarian cinema magazines and production reports, even noting that by the time of the acquisition of DRACULA’S DEATH by Jen? Tuchten’s Filmdistribution Company in 1923, the film took up 1448 meters of film, and was a drama in four acts.

From Tamasfi’s gatherings the first exhibition of the film took place March 21–23, 1923, in the Hungarian city of Nyíregyháza, at the Városi Mozgo Színház, oddly paired with the 1918 Mary Pickford film HOW COULD YOU, JEAN? under its Hungarian title, ?nagysága a Mindenes.

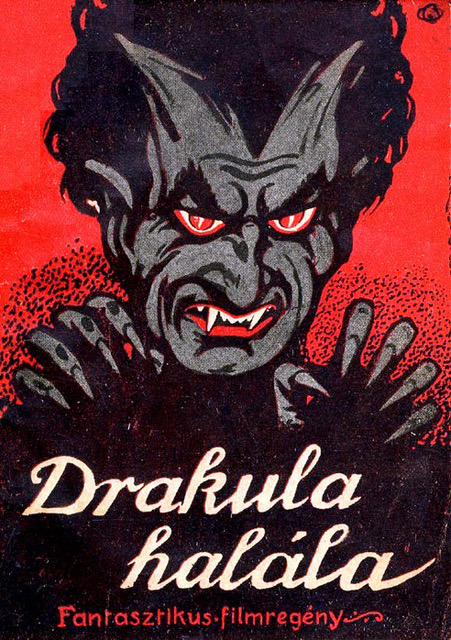

The film was novelized in issue #6 of Lajos Pánczél’s Filmbooks, who also befriended Béla Lugosi before his departure to the United States in 1918 to later achieve his fame as the titular character. No author is credited, and the only credit in the magazine is that of Pánczél’s editorship. This edition was entered into the National Széchényi’s library May 27, 1924, with director Károly Lajthay credited as the author.

This Hungarian-language adaptation, first translated to English by the Hungarian writer Péter Litván and American scholar Gary D. Rhodes, in their 2010 essay on the film’s history Drakula halála (1921): The Cinema’s First Dracula. László Tamasfi offers his own translation of the adaptation in his publication as an additional view of Rhodes and Litván’s work, though not for any corrective purpose. Tamasfi’s joy as a writer spread into his research, and his translation brought him tremendous creative joy to occupy his mind as he was locked away while the pandemic was spreading.

When asked how Tamasfi became so passionate about DRACULA’S DEATH to make it his first publication for his imprnt Strangers From Nowhere, he responds: “I first learned about DRACULA’S DEATH from a short story called A Polidori, written by Viktor Juhasz, a friend of mine. It came out in 2010, and one of the characters in it mentions the movie. As a lifelong horror fan it blew my mind that there was this landmark Hungarian film that I didn’t know anything about!

What drew me to doing further research was the lack of information available. There were some articles dedicated to DRACULA’S DEATH, but they always left me wanting to learn more. In 2019, I decided to make a documentary film about DRACULA’S DEATH, the fate of silent films, and early vampire movies. I went back to Hungary (I currently live in Chicago) and interviewed Istvan Elbe at the National Széchenyi Library, where I even got to hold the lone surviving copy of the novelization. I also interviewed Jen Farkas, a brilliant Dracula expert who was the first vampire scholar in the ’90s to discover the significance of the book.

And then, a few months later, Covid hit, and I wasn’t able to continue filming, or traveling.

But I had gathered a lot of interesting information, and most importantly, I was beginning to answer the questions I was asking. So I decided to turn my project into an essay: I conducted phone interviews with people from the Hungarian National Film Institue, and what was probably the most important breakthrough, I dove into digital archives. There were a few months in the pandemic lockdown when several archives made their digital catalog available for free, and I scrolled through every movie-related Hungarian periodical between 1920 and 1924. Page by page, because I wasn’t solely interested in DRACULA’S DEATH, but also to better understand the film industry of that era. That’s how I discovered that the movie was screened in the city of Nyiregyhaza weeks before its official premiere in Budapest!

By the time I decided to translate the novelization to English I knew that there was already one, which was published in 2010 as part of Gary D. Rhodes’ essay Dracula halála (1921): The Cinema’s First Dracula. Gary is a fantastic scholar, and I have just published another great vampire discovery he made: the very first American vampire novel from 1885, predating Stoker’s tale by 12 years! But as far as the DRACULA’S DEATH’s translation goes: it’s really hard to convey how strange the language of the original book is. It’s old timey, and sometimes feels like a stream of consciousness. So it’s really tricky to translate, because you want to be faithful to the original and want to reflect its tone, but on the other hand, you don’t want it to feel too strange, because it would come across as broken English. But of course the story also has some truly beautiful moments, and I thought that I could perhaps try my hand at translating it, doing my best to stay faithful.”

Sadly, a well-noted phenomenon was the loss of interest in silent films as talkies took over the creative arena. Most Hungarian silent films were recycled for their plastic. Today approximately 7% of Hungarian silent films survived this holocaust of cinema. Tamasfi’s resilience against this loss and possibility for the film’s discovery in some dank basement is stated in his monograph’s final line: As the Hungarian saying goes: Hope Dies Last.

For your own copy of László Tamasfi’s DRACULA’S DEATH, please visit:

https://www.strangersfromnowhere.com/draculas-death

For a copy of the first known vampire novel, the American tale The Vampire, Detective Brand’s Great Case, please visit Strangers From Nowhere site here:

https://www.strangersfromnowhere.com/the-vampire-1

Very special thanks to Tamara Nagy and Janka Barkóczi of the Hungarian National Film Institute for their assistance with this article.

Tags: Aladar Ihasz, Austria, Bram Stoker, Carl Goetz, Count Dracula, Dezs? Kertész, Eduard Hoesch, Elemér Thury, History, Horror, Károly Lajthay, Lajos Gasser, Lajos Rethey, Lene Myl, Margit Lux, Michael Curtiz, Paul Askonas, The 1920s, vampires, Vienna, Viktor Juhasz

No Comments