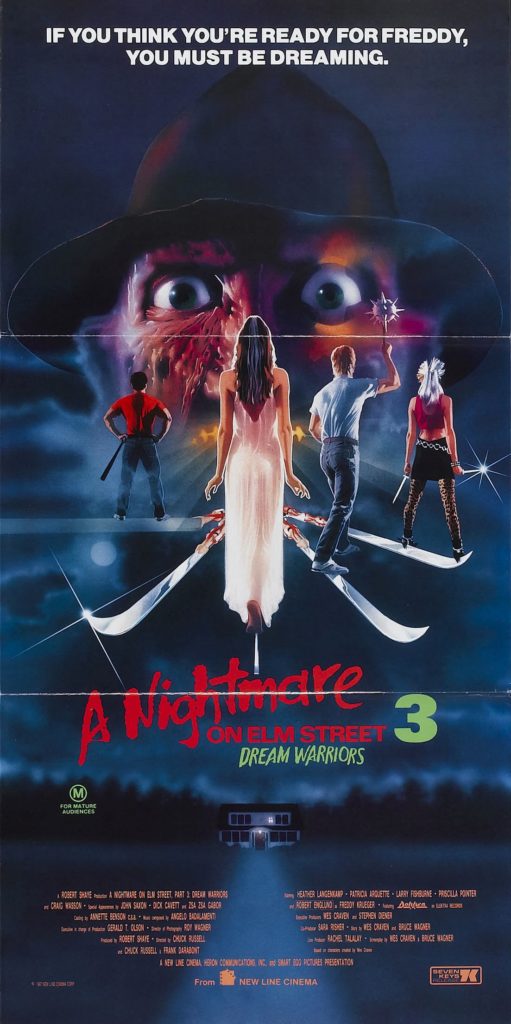

On this day 30 years ago, Freddy Krueger celebrated what many fans consider to be his finest hour (well, hour-and-36 minutes) with the release of A NIGHTMARE ON ELM STREET: DREAM WARRIORS. While it wouldn’t be the peak of “Freddy Mania”—that would come a year later with the release of THE DREAM MASTER—it’s fair to argue that this second sequel stands as the most revered in the franchise. Not only does it expand on Wes Craven’s original by introducing high fantasy concepts, but it also sees Freddy come into his own—this was the guy who wound up hosting MTV and having a day named after him in Los Angeles. Here’s the moment he became a bona fide pop icon who managed to endure overexposure (in addition to popping up in three movies in as many years, he also headlined two seasons of his very own TV show) and, eventually, declining interest at the box office.

Just four years later, Freddy would be “dead,” only to be revived again in a meta spin-off and a crossover with Jason Voorhees. If we’re being technical, we haven’t seen a proper NIGHTMARE ON ELM STREET movie since 1991 (note: this writer does not officially recognize that 2010 mess as an official state). As such, it’s fair to ask if this franchise even has much of a future at all, especially given the radio silence surrounding it as other horror icons make headlines (for better and for worse, but at least they’re registering a pulse). Michael Myers is due back in theaters next year, and Chucky will likely grace our televisions this year, right around the same time SAW returns to continue its legacy. A new Leatherface film is in the can, just waiting to be unleashed. And while Jason has certainly seen his struggles to return, does anyone really doubt we’ll ever see another FRIDAY THE 13th movie?

But what about Freddy? It’s easy to see how the Elm Street franchise poses its own unique challenges, as evidenced by the Platinum Dunes production seven (yes, seven) years ago. Still, it’s hard to imagine those challenges will outweigh WB’s desire to keep making money off of what is still a viable property (as much as I like the goof on the remake, the first weekend’s box office take indicated that there was some interest that quickly waned once everyone realized how bad the movie was). The question isn’t a matter of if but a matter of when—and, most importantly, a matter of how? Just how can you possibly resurrect a franchise that’s been inexorably connected to an iconic character that can’t be replicated by just sticking a new stuntman in a mask each time out?

Any discussion about Elm Street’s future has to start with the red-and-green striped elephant in the room: in the absence of Robert Englund returning (and he’ll be the first to say he’s not—and he deserves as much), there’s no clear answer beyond what not to do. If the remake served any purpose at all, it at least functions as a blueprint detailing the worst possible attempt at recreating A NIGHTMARE ON ELM STREET, mostly because Platinum Dunes did just that: “recreate.” It was both too reverent and a lazy, slavish attempt to photocopy already-iconic images and beats, an approach that feels inherently doomed. This brings me to my first piece of advice:

Forget what you know, especially about Freddy.

Instead, I propose that whoever strolls down Elm Street next needs to forget just about everything they know about the franchise, at least when it comes to the explicit details and particulars. Obviously, you retain the broad concept, including Freddy, but you have to almost turn the entire thing inside out to make it feel like a truly fresh reinvention, starting with the Springwood Slasher himself. This is not a knock on Jackie Earle Haley as a performer, and I will even offer that he did the best he could with what he had—which was not much but a heinous makeup job and an uninspired attempt at redoing Freddy at the script level. At the end of the day, he was just someone stepping into Englund’s formidable shoes, and trying to recreate his shtick to boot (right down to repeating lines of dialogue). Nothing about it worked, least of all because it felt like someone wearing an elaborate Freddy Krueger Halloween costume.

No Elm Street reboot will be successful if the audience finds themselves constantly comparing a new Freddy to the old one, so why make it so easy to invite the comparison? Rather, wouldn’t it be more productive to re-imagine Freddy from top-to-bottom? Granted, some details—perhaps the burn makeup and the glove—must remain, but everything else? Fair game to toss out. The fedora, the sweater, the whole damn thing. In fact, I might even go a step further and suggest that Freddy need not be a huge on-screen presence altogether. In essence, Freddy Krueger is a ghost, so why not start treating him (or her?) as such? Make him a genuine boogeyman who is heard (I think you should retain the character’s dark wit) and felt more than he’s actually seen—you always hear about folks wanting to make Freddy scary again, and this is probably the best approach, if only because it’s not continually asking the audience to remember how Englund did it better.

In fact, Englund himself has argued as much as recently as last year. During an interview with Florida Today, he went so far as to offer his own take on how to re-imagine Freddy:

“If I was in control of my own NIGHTMARE ON ELM STREET movie, I have an idea I would have liked to see. I thought it would be great if the children of previous victims, or just kids who grew up hearing stories about Freddy Krueger, were each haunted by their own version of Freddy Krueger. Kids who grew up hearing stories about this Freddy Krueger guy and the awful things he did envisioned him in their own way, and that is the version that begins to haunt them. Some people may picture him as stout, another might envision him as tall & thin, another with a different hat, or a different sweater. He could have different gloves, or even a glove with small razor blades as referred to in the first movie. It would be neat to see very different interpretations of Freddy Krueger based on the child’s vision of who or what Freddy was to them. After all, each person’s subconscious would picture him in a totally different way.”

This is exactly the sort of unconventional approach the next NIGHTMARE movie should take—after all, can someone really make this property their own if they’re unwilling to retool Freddy himself?

Embrace the full potential of the title.

Craven’s title is one of the most immediately evocative in all of horror, if only because it’s loaded with multiple implications. Literally, it refers to the premise itself and the deadly nightmares suffered by the characters; metaphorically, it hints at the horrors of a quaint, suburban town coming undone by repressed sins. The next NIGHTMARE ON ELM STREET film would do well to remember both. Obviously, audiences crave the sort of memorable, outlandish dream sequences that made the sequels so popular, but I’ve always found Craven’s film is most potent in those eerie moments of stillness, when the line between nightmares and reality have been blurred. Given the looping nature that Craven’s original ending implied, it always felt like he was taking a cue from PHANTASM’s blurry, dreamy sense of surrealism.

At this point, any new ELM STREET probably carries certain commercial expectations, but how cool would it be to see a return to the arthouse take lurking at the center of Craven’s film? Why not go full PHANTASM and create a film that feels like a constant waking nightmare? If Freddy isn’t a constant on-screen presence, make the nightmares—and perhaps more importantly, the nightmarish feeling—the centerpiece. Consider just how effective Craven’s original film was on a limited budget—he might not have had the budgets and special effects at his disposal that the later sequels had, yet the first NIGHTMARE captures the horrific dread of nightmares better than any of them.

What’s more, Freddy himself barely appears for the two most infamous sequences (Tina’s gruesome, wall-crawling evisceration and Glen being reduced to chunks of viscera), and I’d argue they’re more effective because of this. As fun as it is to watch Freddy drop puns while killing his victims, there’s something to be said for how Craven creates a genuine terror out of the inexplicable scenes that unfold in the first film. I’d argue for a return to something along these lines: make Elm Street weird and unfathomable again by invoking hazy nightmare logic throughout. If this means I’m calling for a more competent version of FREDDY’S NIGHTMARES, then so be it. I’d like to see a NIGHTMARE ON ELM STREET that, well, feels like a nightmare at all times: somewhat bewildering, maybe even a bit alienating—not because the audience is being assaulted by wall-to-wall jumps and shocks but because they’re being slowly suffocated under a dreamy, oppressive haze.

Finally, remember that the franchise wasn’t only about Freddy.

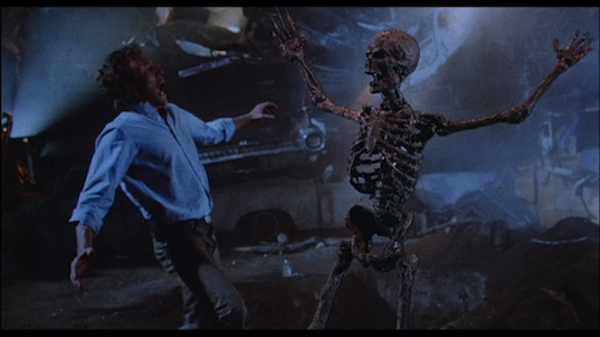

In fact, look at the subtitle for movie whose anniversary inspired this article: DREAM WARRIORS. From the beginning, this was a franchise that obviously valued characters beyond their potential to serve as fodder for Freddy’s blades. An “us vs. again” dynamic pervades the franchise as it relates to the teens’ struggle with the adult figures in their lives, and that was never more obvious than in the third film. Each of the Dream Warriors is endearing in their own ways, even though most of them are obvious clique stereotypes: a nerd, a “bad girl,” a mouthy rebel, a girl who dreams of becoming a big Hollywood star. Under any other conditions, this group would never be together, yet there’s a palpable kinship between them. It actually sucks when Freddy kills them, be it in this film or the next, when he claimed last of the remaining Elm Street children. And don’t even get me started on the total gut-punch that is the cruel death of Nancy Thompson—how many character deaths feel like that big of a deal in slasher movies?

Even as Freddy’s presence as sardonic anti-hero grew larger, filmmakers resisted introducing characters solely to have them die. Maybe they were even more broadly drawn high school clichés, but realized with affable performances that make the m personable—even a guy like the “dumb jock” Dan somehow becomes one of the franchise’s best characters. Unlike other slasher franchises, A NIGHTMARE ON ELM STREET doesn’t feature a single character whose death feels like a punchline or yet another addition to the body count (well, until FREDDY VS. JASON, anyway, but we’ll blame the FRIDAY THE 13th DNA for that). There’s a definite empathy extended towards the characters in Elm Street that sets it apart from its contemporaries, and it’s among the most critical things to retain going forward.

If you figure this out and develop compelling characters, you’ll even help to solve the lingering Freddy problem: one of the reasons the remake unimpressed is because it had nothing going for it in this department (despite boasting one hell of a cast, mind you), which only compounded how awful Freddy was. I’m pretty sure I spent most of the time wishing Englund were around to liven things up and make quick work of these boring kids, something I can never remember thinking during any other Elm Street movie. In the future, I hope the opposite is true: I hope the characters are so endearing that it makes Freddy’s presence even more harrowing.

How odd would it be to see an Elm Street film where Freddy felt like a legitimate villain again? Pretty odd, I’m sure, but that’s preferable to feeling nothing. And besides, “pretty odd” is the sort of thing I would want from this franchise going forward; while I think you can get away with sticking to the FRIDAY THE 13th formula from here to eternity, there’s no reason for Elm Street to be limited by anything beyond its rather broad concept. I’d like to see something genuinely intriguing whenever they announce the next film—I mean, there’s a reason everyone was abuzz about learning David Gordon Green and Danny McBride had boarded Blumhouse’s upcoming HALLOWEEN revival. None of us saw it coming, and while time will tell if it yields a worthwhile film, there’s at least some interest and optimism. How can you not be curious about that pairing?

Ultimately, that’s what I’m hoping for with this franchise as well. As horror fans, we tend to be a pretty insular bunch, which explains why we tend to recycle the same genre names and try to attach them to obvious franchises (raise your hand if you were also convinced Mike Flanagan would be directing the next HALLOWEEN). Sometimes, though, it’s okay to step outside of the box and welcome an unexpected approach to the fold. Never would there be a better opportunity to prove this than with the next NIGHTMARE ON ELM STREET, a film that would be ripe for someone with an actual vision to mold into something worthwhile and memorable. Preferably, this is how its existence would begin: with someone making an impassioned, creative pitch rather than Warner Brothers half-heartedly commissioning a vague new film, as has been rumored in recent years.

Well, unless it involves putting Englund in the glove for once last hurrah—in which case, forget everything I’ve just said and go ahead and take my money.

— BRETT GALLMAN.

Tags: A Nightmare On Elm Street 3: Dream Warriors, Chuck Russell, Frank Darabont, Freddy Krueger, Horror, Robert Englund, The 1980s, The Future, Wes Craven

No Comments