There’s a phenomenon that occurs with creatives not a lot of folks talk about—that we don’t like—to talk about, but, I’m going to let you in on a little secret: artistic success is an addiction. It starts out small: when you’re young, just starting out, the idea that someone—anyone—would read something you’ve written, see you perform in a community play, that you might get a bit part in a television gig, is the absolute world. It’s enough. The idea that you’ve impacted a single person, been seen by even one television viewer, means that you’ve made your mark. Once that’s happened, though—once you’ve been seen by that one person—well, now you want a little bit more. Now it’s about cult status. If you’ve just got a following, if a cadre of folks know you and your work, if you can just be a footnote in genre history or the answer to an obscure trivia question… well, now, that’s enough.

And so it goes.

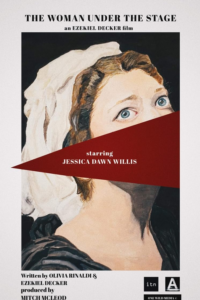

For every kid who dreamed of superstardom there’s countless other creatives who started out wanting something small, only for the goalposts to keep moving further and further upwards into the stratosphere of achievement. God knows that’s been the trajectory of my life. And just like any other addiction, that nebulous, undefinable thing that is artistic success can, and often does, destroy those who seek it out. That’s the fascinating, unique conceit at the heart of THE WOMAN UNDER THE STAGE, a fresh piece of arthouse horror that explores the very nature of what it means to create, and how that creation can lead to destruction.

Whitney Bennett (Jessica Dawn Willis) has a lot of problems. An aspiring actress, she’s working a soul-crushing barista job and living in a drab, barely furnished apartment, much against the wishes of her well-meaning but stubborn boyfriend Josh (Robert Gemaehlich), who insists he can support the both of them. What he can’t do, though, are resolve those problems of hers, all of which revolve around those artistic aspirations. See, Whitney was recently cast in a potentially groundbreaking production of Macbeth, but the pressure of a starring role and latent fear of success proved too much, which led to a suicide attempt, which led to a lengthy hospital stay, which led to the crushing debt that Josh can’t pay off and which is keeping her behind the counter of that coffee shop.

Fearing that she’s going to end up like her mother—herself a would-be stage star who abandoned her career to raise her daughter—Whitney jumps at the opportunity when she’s invited to audition for a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity. Local director Terrence Durrand (Matthew Tompkins) has gotten the rights from the estate of Hewlett J. Grant to stage the first ever production troubled playwright’s final work, albeit on a series of very specific conditions. The actors and crew must move into the theater where it will be performed for two months, fully immersing themselves in their characters and the world of the play; the play must only be performed once, on opening night; and, immediately following the end of the play, Durrand must burn all of the copies of the script, thus wiping the play from existence.

Despite some initial hesitance—Durrand is an intimidating method director from the Stanley Kubrick school of brooding intensity, and moving away from Josh for two months probably isn’t the best thing for their struggling relationship—Whitney jumps at the offer. Not only does it come with a healthy payday, but, she reasons, participating in something so historic will be her opportunity to finally make her mark. As Whitney soon learns, though, there are certain details about her impending ordeal she may not have been prepared for. The first is the play itself, a sort of Greco-Roman-Shakespearean fusion about a family of crypto-pagans living during the War of the Roses, who are prompted by their patron deity—a reimagined, feminine incarnation of Dionysius—to sacrifice one of their own in order to survive the conflict with their riches intact. There’s something about the play Whitney finds personally upsetting, though she can’t quite put her finger on it. She may be helped along by the second unexpected detail, which is that she’ll be studying under the acting tutelage of her costar, the semi-famous stage star Phillip Costigan (Phil Harrison), who shares Durrand’s dedication to method and who engages Whitney in a series of intense acting sessions intended to break down the barrier between her personal identity and that of her character. It’s the last few details Whitney learns deep into production that prove the most unsettling though, and they all revolve around death. The reason this is Grant’s last play is because he killed himself the night he completed it; the last time Durrand tried to stage the play, the actress playing Whitney’s part committed suicide; and, in the final sequence in which Whitney’s character is meant to die, Durand insists on using a real knife. As the clock ticks down to opening night, costars vanish from the production, and Whitney becomes convinced the theater is haunted, she’s forced to make a decision: flee the production and potentially save her life; or stick with it and risk paying the ultimate price for the ultimate fame.

Cowritten by Decker and Logan Rinaldi, STAGE wears its theatrical influences on its sleeve, a result, Decker says, of his having grown up surrounded by theater people, especially Gemaehlich, an accomplished Shakespearean actor and former member of Dallas’ Shakespeare in the Park. Although it originated as a low-budget slasher-short about an actor slaughtering their costars, when Decker made the acquaintance of producer Mitch McLeod, who was in search of a follow-up project for his Absentia Pictures label following his own directorial effort SILHOUETTE, he saw the opportunity to make it into something more. Says Decker, “I like a good popcorn blockbuster but I also like a good arthouse film. I think originally, as a short, ten years ago, me and my buddies just wanted to make a bloody, fun YouTube video. But I’m older now. I liked the idea of maturing it. What ideas about art and commitment to art can I explore in this?”

So it is that STAGE often feels like watching a filmed play, in all the best of ways. In an instance of life-imitating-art, cast and crew were forced to essentially move into Richardson, Texas’ Core Theater for months of overnight shoots, filming from dusk til dawn on a tight schedule and with limited resources (the film was shot for $30,000, though it looks much more expensive than that- and certainly more polished than some indy productions with higher budgets). The result recalls some of the stripped down, theatrically-influenced work of mid-career Bergman (especially THE RITE, which shares several thematic similarities). It’s an intimate, claustrophobic experience that firmly places the viewer in Whitney’s headspace for the duration of the film. That experience is enhanced by the talents of Willis, who carries the part—and thus the movie—with aplomb. Beginning the film projecting an air of constant anxiety that only becomes amplified first by dread and then obsession, her performance recalls a more glamorous Shelley Duvall in THE SHINING. Carrying herself tightly wound and with an expression that looks like she could break out into hysterics at any moment, Whitney’s desperation radiates offscreen, ensnaring the viewer in the mind and body of someone whose desire for her “name to mean something” might only be sated by death.

Buttressing Willis are the one-two punch of Tompkins and Harrison, each of whom bring a tightrope blend of avuncular concern and swaggering menace to their parts. For the duration of the film it’s never quite clear whether they’re just really intense theater guys whose dedication to their jobs may be even greater than Whitney’s, or if there’s something more sinister at play. Particularly striking are a series of one-on-one sequences in which Costigan and Whitney engage in an acting exercise that’s half roleplay scenario, half ad hoc therapy sessions, with Costigan weaving between the roles of himself; Whitney’s on-stage father; and a sort of godlike figure probing the implications of the play and what they mean to both Whitney the woman and the character. Harrison switches up playing Costigan as part drill instructor, part old stage hand, alternating between battering Whitney with troubling questions and teasing out deeper and deeper revelations about herself and her life. They’re a joy to watch not only in the energy that each performer brings to the screen but in the way they enhance Whitney’s psychological verisimilitude, and therefore that of the film.

Equally compelling are the scenes Durand shares with Whitney, where he alternates between the persona of brooding god director we get to see In rehearsals and someone a bit more vulnerable. Early on, Durand plays Whitney a piece of music by a composer as equally obscure as the play they’re about to perform; it’s a shockingly vulnerable moment for a character who could easily be written as a one-note bully. Instead, the script allows us some rare glimpses of sensitivity and hidden depths, and Tompkins does well to soften himself just enough so that we can understand that, while there may be some cracks in his armor, he’s the one who’s put them there, and he’s only going to let you look inside for so long.

Ultimately, though, it’s Decker and Rinaldi’s script that’s the real star of the show here. It would have been easy—and acceptable—to make “just” a thriller about an actress who’s afraid her costars are really going to kill her. Instead, the scares are minimal and well-spaced (if there’s one bit of criticism to be had about the movie, it’s a reliance on some jump scares and SFX that can tend to detract from the subtler elements at play), letting the film exist in the unique realm of the dramatic horror. All of those psychological insights into Whitney help the film evolve into something else: an exploration of what artistic satisfaction looks like, and what happens after someone’s achieved it. STAGE asks a lot of provocative questions, many of which don’t ever get explored in media dealing with show business. Is Whitney really willing to die for any modicum of success? Are her costars really willing to kill her? Would that death be success? Further, without spoiling the film’s ending, there’s another question at the very heart of the movie, and the one that hangs over it most profoundly: what happens when success becomes a matter of forever chasing the next big hit?

THE WOMAN UNDER THE STAGE was produced by Absentia Pictures and distributed by ITN. It’s currently streaming on Amazon Prime and Vudu.

No Comments