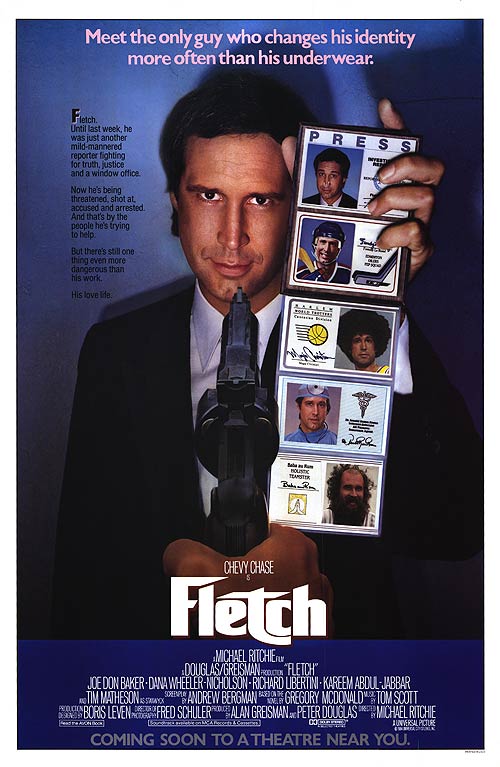

It was a balmy spring day in the northern metropolis of Calgary; the air was filled with the scents of rosemary and lilac. I was trying to ignore the hoopla outside: the overly loud McDonald’s drive-thru speaker across the street and the raucous bikers lined up in an informal motorcade on the street, eager to test out their hogs on the open road. They were distractions, but I had a deadline and I didn’t want to disappoint my intrepid editor, Jon. My name’s Jason, but I go by “Jay” (despite being told rudely by an English professor in my first year of university that “Jay” isn’t the “proper” shortened version of “Jason”, but I digress). By day, I pass as a sad cubicle dweller who drinks terrible office coffee, but by night, I’m a writer, toiling away at my novel and detouring occasionally with non-fiction pieces about movies. Today’s deadline was all about my personal history with a classic ‘80s comedy, FLETCH, one of my favourites, so I had to do some digging, reflecting on my childhood in that lively decade of Ronald Reagan, hair metal bands, acid-washed jeans, and DEGRASSI JUNIOR HIGH. It’s hard to believe that FLETCH is 35 years old — I don’t remember much about 1985 (Max Headroom schilling New Coke and the Toronto Blue Jays winning their American League division — take that, Yankees and Red Sox — are my few highlights), but I remember the first time I saw FLETCH on home video, and it’s become one of my favorite comedies. Chevy Chase as Irwin M. “Fletch” Fletcher became one of my heroes, a dedicated, but irreverent investigative reporter (whose newspaper byline is “Jane Doe”) seeking truth, justice, and a few choice ad-libs at someone else’s expense.

Based on former teacher/journalist Gregory MacDonald’s FLETCH novels, the film is a faithful adaptation of the first novel’s plot, though Chevy Chase’s interpretation is less prickly and more loveable. I’m sure there are purists who blanch every time they think of Chase in the titular role, but having read only the first novel (years after seeing the movie), I enjoyed the differences — fiction and films have different requirements and expectations and I don’t believe the film strays that far from the source material (You want a departure from source material? Try the ‘70s- ‘90s Bond films that have little in common with the original Ian Fleming books — invisible cars anyone?). I don’t think Chase could have played a misanthrope effectively in his ‘80s cinematic heyday — he’d leave that for his stormy exit from ensemble comedy TV series COMMUNITY decades later.

I didn’t see Chevy Chase on SATURDAY NIGHT LIVE reruns until my early twenties, so I didn’t know how adept he was at improv comedy (I was raised on a steady diet of SCTV and THE KIDS IN THE HALL). I also hadn’t seen NATIONAL LAMPOON’S VACATION or CADDYSHACK and the only Chevy Chase comedies I had seen at the time were dreadful comedies like OH! HEAVENLY DOG and DEAL OF THE CENTURY (the latter prompted my dad to announce, “What a piece of shit,” after we finished watching the rental tape. My dad, the succinct critic!). I discovered FLETCH on home video around the time my Aunt Donna had taken me to see SPIES LIKE US at the movie theatre in early 1986, so I became fond of Chevy Chase quickly. As Fletch, Chase exudes natural charm, wit, and preternatural obfuscation skills that I admire tremendously. He’s committed to his investigative reporting, but always has time for a quip or shameless flirting (To lead female character, Gail Stanwyck (the winsome Dana Wheeler-Nicholson), who’s gotten out of the shower: “Can I borrow your towel? My car just hit a water buffalo.”). On set, Chase improvised a lot of his dialogue and it’s pure mastery of craft in action. There are too many scenes to list, but I love the doctor’s examination scene with the great M. Emmett Walsh: Fletch mumbles his way successfully through a fake cover story, only to encounter an unexpected proctological exam (“Ever serve time, Doc?”). Chase’s rapid-fire delivery is exhausting, but hilarious:

Dr. Joseph Dolan: So where do you know Alan from?

Fletch: We play tennis together at the club.

Dolan: Really? The California Racquet Club?

Fletch: Yes.

Dolan: That’s my club too. I don’t remember seeing you there.

Fletch: Well, I haven’t played in a while because of these kidney pains.

Dolan: Right. Now, how long have you been having these pains, Mr. Barber?

Fletch: That’s Babar.

Dolan: Two bs?

Fletch: One. B-A-B-A-R.

Dolan: That’s two.

Fletch: Yeah, but not right next to each other. I thought that’s what you meant.

Dolan: Isn’t there a children’s book about an elephant named Babar?

Fletch: I don’t know. I don’t have any.

Dolan: No children?

Fletch: No, elephant books.

On a recent viewing, I had to pause repeatedly, as my laughing fits spilled onto the next scene (and irritating my cat, Snaus). An ordinary mortal would be caught in one of the first lies, but not Fletch — he gets away with a lot of chicanery (unless he’s dealing with the police). Even when his improvisational antics don’t impress a Utah redneck, a quick kick to the crown jewels works nearly as well. A standout sequence is a car chase that ends with Fletch running into a crowded retirement banquet for Fred Dorfman (a nod to NATIONAL LAMPOON’S ANIMAL HOUSE) — Chase is a spontaneous tour-de-force, becoming a temporary master of ceremonies, evading the police in brilliant and riotous fashion. If you don’t find the scene funny, YOU’RE DEAD INSIDE.

Part of FLETCH’s appeal isn’t so much the plot (there is one, but it’s not important — it serves to propel Chase’s guises and wordplay), but the talented cast of supporting characters, assembled by director Michael Ritchie, a filmmaker who made some brilliant films (PRIME CUT, SMILE) and some cinematic turkeys (THE ISLAND, COPS AND ROBBERSONS). Dana Wheeler-Nicholson is a delightful counterpart to Fletch and it’s a shame she never got many leading roles afterwards. She’s given good lines with pitch-perfect delivery: “Utah’s not exactly a cure for boredom.” Fletch is clearly smitten with Gail, a credit to Ms. Wheeler-Nicholson. Tim Matheson continues his downward spiral of evil yuppie characterizations in the ‘80s, though he’s suitably smarmy here as the guy who misleads Fletch with a bogus murder attempt plot (I told you the plot isn’t important). Geena Davis, on the brink of stardom, has a small but memorable role as Larry, one of Fletch’s colleagues at the newspaper. Even in her few scenes, Davis displays serious star power — it’s easy to see why she broke out a year later with THE FLY. There are so many talented actors, from both comedy and drama worlds, but they make the film richer with their presence. I can’t imagine anyone else but Joe Don Baker as the crooked police chief, George Wyner as Fletch’s ex-wife’s relentless lawyer seeking alimony, George Wendt and Larry Flash Jenkins as a couple of beach-bum junkies, or Richard Libertini, as Fletch’s long-suffering editor. There are so many blink-and-you’ll-miss cameos from recognizable character actors, including the Doberman who’s excited by the mention of “defenseless babies.”

I would be remiss if I didn’t highlight the various aliases Fletch uses, ranging from the juvenile to the sublime. I still whoop with laughter like a twelve-year-old at the mere mention of “John Cocktolstoy” (or his cousin, “John Cocktoastin”), “Mr. Poon,” or “Dr. Rosenpenis.” He enjoys American history, using “Harry S. Truman” while investigating in rural Utah (as well as the aforementioned “mattress policeman,” after “Don Corleone, Mrs. Cavanaugh’s cousin” fails to impress the Utah hick, but he’s in a land in which motel clerks are mesmerized by Mr. Potato Head playing silently on TV), and airplane mechanic “Gordon Liddy” (Chase revels in this disguise, using fake teeth and slicked-back hair (“I splurged, I invested 49 cents in novelty teeth.”). He daydreams being Kareem Abdul-Jabbar’s teammate on the L.A. Lakers (has there ever been as big a basketball fan in film history? His idea of a perfect date with Gail is to take her to a Lakers game!) and delights as a roller-skating guru (with bald cap, long grey beard, and men’s night shirt, one of the few instances where Chase resorts to physical comedy). As a member of the “Smog Patrol,” Fletch borrows a convertible with a terrified teen car thief along for the ride (and never-ending jokes), fleeing the police as requisite ‘80s pop music plays in the background. It looks a typical Hollywood ‘80s comedy, but Chase and Ritchie collaborate to make every alias count for maximum comedic effect.

FLETCH stands out as a superior film from a period where Hollywood was churning out hundreds of comedies (and POLICE ACADEMY sequels). The collective efforts of Michael Ritchie, Chevy Chase, and the supporting cast give life to a memorable literary character (By the way, purists, did you know that Gregory MacDonald had final casting say for his creation? He thought Chase was ideally suited for the role.). Thirty years later, I still laugh uproariously, a rare experience with most comedies (unless it’s revisiting old WKRP or GET SMART episodes on DVD). I think it’s Chevy Chase’s best role and so does he — so much so that he and Michael Ritchie returned with FLETCH LIVES in 1989, a reliable, if somewhat sloppy, sequel (And COPS AND ROBBERSONS in the mid-‘90s, but good art is hard to create.). If it weren’t for FLETCH, I might never have discovered other irreverent heroes, like James Garner’s Jim Rockford of THE ROCKFORD FILES, a character cut in the same mold as Gregory MacDonald’s character (both first appeared in 1974). Fletch is an incorrigible character, a man who doesn’t suffer rich assholes gladly (just ask Ted Underhill), but that’s what I love about him.

Tags: Andrew Bergman, Books, chevy chase, comedy, Crime, Dan Hartman, Dana Wheeler-Nicholson, Fred Schuler, Geena Davis, George Wendt, George Wyner, Gregory Mcdonald, Harold Faltermeyer, joe don baker, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, Kenneth Mars, Larry "Flash" Jenkins, Los Angeles, Michael Ritchie, Phil Alden Robinson, Richard A. Harris, Richard Libertini, Stephanie Mills, The 1980s, Tommy Lasorda

Good article. Can never have enough Underhill references.