“POSSESSION is essentially a very true-to-life autobiographical story. As I said even the kitchen dialogue is remembered and transcribed. What’s untrue is the monster, all right… POSSESSION is a fairy tale for adults.”

— Andrzej Zulwaski, “Cinema Superactivity: Andrzej Zulwaski Interviewed by Stephen Thrower & Daniel Bird.”

“[Divorce is] a life experience my friend Brian compared to ‘having a really bad car accident every single day for about two years.'”

— Elizabeth Gilbert, Eat, Pray, Love.

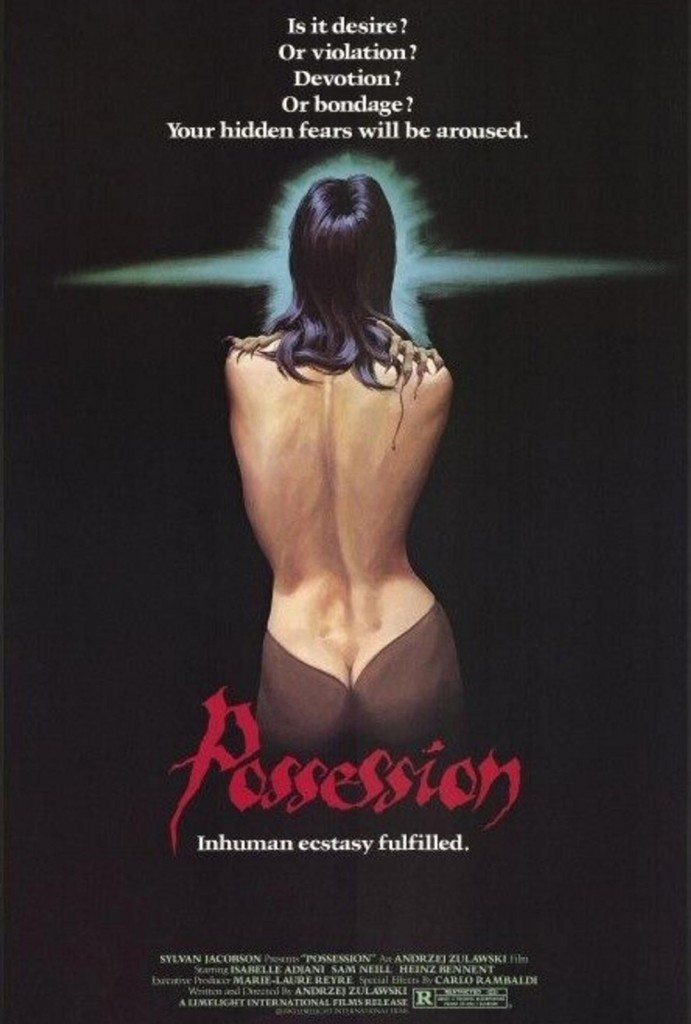

Many people walk away from the film POSSESSION in a state of confusion and awe. What is this puzzle, this mystery, this enigma? While I think filmmaker Andrzej Zulawski intended for his film to create this deep sense of wonder and awe, I don’t necessarily think he intended to create an enigma or a puzzle. All of the keys to unlocking the film are inside the film itself. And I submit to you the only critical context you need to understanding or unlocking the film: Zulawski himself has explicity gone on the record as stating the film is autobiographical, and specifically about the breakdown of his marriage to the Polish actress Malgorzata Braunkek. And I submit the only thing a viewer needs to implicitly understand about the film to read it through this lens is to have one thing happen to them: to have a person you love more than anything in the world leave you. When the film is viewed through this lens, suddenly everything about it makes sense. Is that too hard to endure just to understand a film completely? You’re probably right, I don’t blame you. In that case, take my loss as your gain, as I walk you through my reading of the film.

Having always been a fan of bizarre and underground cinema, I first encountered Possession in my mid-twenties via a underground film sharing. During that time, I was mid-way through what read, at least to me, as a contented marriage. Watching the film on my laptop, I experienced the shock and awe most first-time viewers probably do. That panic in the subway…what is it about? And Isabelle Adjani fucking a tentacled monster? I somehow intuitively understood it was about really important things, but couldn’t quite put my finger on what those were.

All it took me to understand it was— you guessed it—seeing it at the Siskel Center during its revival, conveniently timed about two months into my own messy divorce. Here is my even more nuanced read of the film, three years in recovery from the event. Possession is an incredibly rich, complex, and nuanced film, and can be read through many lenses—Polish history and mythology, religion, the psychology of color, and others. The reading is strictly through the lens of a divorce surivivor.

The film opens with panning shots of Belin decay. Sam Neill, playing the hapless husband Mark, pleads with his departing wife Isabelle Adjani, or Anna. Indicative of the push-pull nature of their relationship now, he lifts his bags, sets them down again, lifts them up again. Their language has become the circular conversation of people who still love each other, but don’t; who can’t stand to be without each other, yet can’t stand to be around each other anymore. “You say ‘you don’t know,” he cajoles her. “I don’t know,” she replies.

A cut to the couple’s son, Bob, innocently playing in the bathtub, raises the stakes. There is a child involved; they cannot leave each other completely.

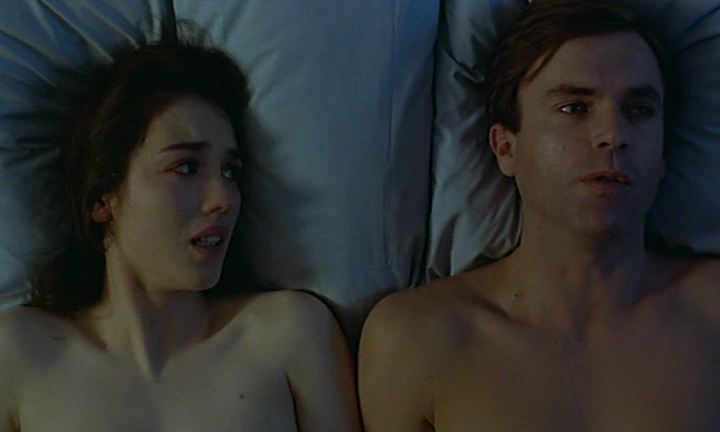

Anna and Mark lie naked, side by side, in bed. The circular, probing conversation continues, conversation circling around the point. Has someone been unfaithful? That is usually the case in instances like these. Not really. Could this just be something that happens naturally, over time?

The next scene portrays Mark at work. He works for a mysterious spy agency; work has taken him away from home, and he begs off his next case to work on his family, who he has been neglecting. His successor is to be a mysterious acolyte in a pink sock.

Next we see Mark huddling, terrified, in his all-too-empty home…a scene not unfamiliar to anyone who has experienced slow, painful separation. The spies are now watching him outside his window in a role reversal, as he now waits for Anna the way she must once have waited for him. She calls him, and their meaningless conversation is now his umbilical cord to the real world.

Somehow Mark is able search he and Anna’s shared bookshelf and immediately uncover what has been there all along, evidence of a lover, Heinrich, and his message on a postcard. Mark calls Anna’s only close friend, Margie, who confesses that Anna has been seeing Heinrich, all while hoping for a “magic wand” that could somehow resolve she and Mark’s marriage. The “magic wand” metaphor is common in situations like these, and was brought up at least a few times in my own therapy—I can only imagine Zulawski dealt with it as well.

Mark confronts Anna with all the passion and sense of a jilted lover, asking questions like “How long has this been going on? Do you sleep with him? Where do you intend to live now?” As if any of them mean anything, all while demanding to know the answer, of course, right now.

Mark and Anna meet in the public safety of Café Einstein (logic in a situation defying such), not facing each other, making a terse series of negotiations about living arrangements and their child, Bob. The scene devolves with the two of them shouting in public, destroying furniture, chasing each other out the door, with Zulwawski’s never-still camera following and crazily swirling around every violent motion. Did they really cause this scene, or is this just how it felt emotionally? And does it even matter, in the end?

An unmarked passage of time shows Mark attempting to call Anna, breaking into sweats and seizures, and finally being kicked out of a hotel after what he has found is three weeks, to return to his son Bob, obviously having been neglected in a disheveled home. Little Bob, covered in condiment stains, brings out a boat that his new friend Heinrich has given him. Of course, Mark had the typical spurned lover’s compulsion to know, when? Long ago.

Mark is rocking crazily in their rocking chair when Anna returns, a beautiful visual metaphor of domestic bliss gone askew. He wants to take care of Bob now. He gives Anna the classic ultimatum: she must make a choice, but either way, she must go to Heinrich and let the family fend for themselves, or come back to the flock. Anna cannot choose, and as Mark still loves her, he cannot resist nurturing her and tucking her into bed.

Anna mysteriously disappears again—this time neither Heinrich nor Margie know where she is. Mark takes Bob to school and first meets his teacher Helen, Isabelle Adjani’s doppelganger. “What is this, a joke? Your wig?” Mark asks her, referring to her identical appearance to his wife, other than bright green eyes and her hair. It makes sense only to someone who has undergone the first pangs of a crush after a painful separation that the first things that would kindle your interest about a possible new flame—someone as kind, nurturing, and intelligent as Helen would fit that bill for Mark—would painfully remind you of your lost love.

The fierce lover Heinrich, played animatedly by Heinz Bennent, offers some of the film’s necessary comic relief. According to some critical speculation, Heinrich is indicative of a specific type of Polish counterculture intellectual which Zulawski despised, and may also represent Andrzej Krajewski, the Swedish translator and Buddhist teacher Braunek left Zulawski for (page 14 of Possession disc notes, in an essay by Daniel Bird, published by Mondo Vision 2014). He invites Mark over and attempts to bond with him over their shared suffering for Anna’s well being. Heinrich is able to give Mark a few of the answers he has been seeking: he has been seeing Anna for a year. Though they have reached “perfect harmony” sexually, he has given Anna every chance to decide for herself what to do. He seems almost too kind and Zen to resent, until he gently beats Mark bloody with what appears to be some enlightened form of martial arts.

Mark then intrudes on a beautiful domestic scene between Anna and Bob in the kitchen. Anna’s features, relaxed and maternal, immediately tense when Mark enters the room. When Mark demands to know where she has been, Anna becomes loud, defensive, and violent again. Mark grows agitated alongside her, claiming she now disgusts him, and that “Love isn’t something you can switch from channel to channel.” They physically wrestle and break things again, until Anna slaps him, he dares her to do it again, and she smiles maniacally at him before fleeing for the door. Mark then retaliates by slapping her back and forth for her “lies.” Seeming to draw power from her bloodied face, Anna flees, and when Mark tries to chase after her into the street to follow her, she cries in an ominous tone, “Don’t even try.” As she stalks away looking possessed, a car falls off a nearby truck dolly, as if in deference to Anna’s newfound kinetic power.

“Don’t even try.” Isabelle Adjani gains newfound power from violence in POSSESSION.

In the next scene, Margie meets Mark in an alley, blatantly attempting to seduce him (forcefully removing articles of his clothing) while offering to help with Bob. Mark resists, telling Margie he loathes her. Mark is then seen hiring a private eye to tail his wife, to find where Anna goes when no one can find her.

When Mark comes home that night, after he puts Bob to bed, he must contend with a seductive Margie once again, to the ambient noise of dogs barking in the distance. Margie is draped across his bed with a cast. However, spies are clearly peeping through his window again. Is it a trick? Is Mark meant to be unfaithful as well, so he and Anna can share the same moral playing ground?

In the jarring way separated couples are often forced to inconveniently share space when they don’t want to the most, Anna is at the apartment in the morning again, grabbing possessions. It should be noted she appears in the same dress she has the last few scenes, which seems like a beautiful blue relic of the Victorian era, except it looks increasingly dirty, with less of the back buttons buttoned. (Zulawski has also gone on the record saying he quite explicity used color in the film: “In most theories of colour blue is the colour of rejection of the heartand yellow is the colour of passion, the real of the senses… Goethe said the same, and the Sufis” (Zulwaski in interview with Thrower and Bird, ibid.)

In a not-too-subtle visual metaphor, Anna is grinding meat. Anna says exactly what is on her mind: “When I’m away, I think of you as an animal, and when I see you again, all this disappears.” Mark begins questioning her about her intentions with Heinrich until she takes the meat grinder to her own skin. Mark’s final question is about whether Anna fears he will beat her again, showing Zulawski is ever mindful of Mark’s role in the failure of the relationship. Mark, seeing Anna bleeding and in such distress, falls easily into his old role of nurturing partner, and takes her to the bathroom to administer first aid. In this unexpected moment of tenderness, Anna sheds tears, and the ambient noise is children playing outdoors. Hope.

Soon, though, Anna is leaving yet again. Mark has now cut himself several times casually with the meat grinder, and has himself positioned as if he is on the chopping block. “It doesn’t hurt,” Anna tells him before leaving. Cutters often describe creating a ritual of physical pain as a tolerable distraction to emotional pain.The meaty (I couldn’t resist) subtext of the scene: cutting themselves with the meat grinder, of course, does not hurt as much as that conversation just did.

“It doesn’t hurt.” Grinding meat in POSSESSION.

Anna becomes increasingly distracted on her next journey away from home on the subway; so much so that a vagrant roots through her grocery bag and eats, perhaps symbolically, a banana. She totters in her severe heels through an obviously decaying and graffiti-coated area of town, to a towering decrepit building that looks like it was once beautiful, but is now rotting from the inside out (everything here is a visual metaphor).

Mark’s private eye is trailing her up the cavernous spiral staircase, a handkerchief held over his face to ward off the stench. He bangs on an impossibly tall set of doors, taller than his height times two. He rings the hollow, echoing bell. Finally he enters and Anna is defensive, mumbling. He poses as a window maintenance man, pulling up shades and draperies in every room. Anna, feeling desperately cornered, maniacally offers him wine. An idea dawns on her. “Ah, broke!” She cries out as she drops the bottle. She knows there is no other solution for what the detective is about to see. This is the film’s first reveal of its monster. Here, it resembles something close to a bloody outgrowth of the wall, possibly a sexual orifice, breathing, pulsing. It is still enough to inspire horror. Anna stabs the detective repeatedly with the broken bottle, then looks surprised at her own behavior. There was, however, no other choice.

Cut to Mark playing innocently with Bob in the bathtub. Bob is counting how long he can hold his breath, when who stops by but the mysterious teacher Helen. Here is where she supposedly first learns about Mark’s separation. Heinrich calls and wants to confront Mark about their “triangle” again—he can’t find Anna. Mark reveals there is a third party even Heinrich doesn’t know about. “There is nothing to fear but God—whatever that means to you,” the first reference in the film to the third party as a divine force. When Mark returns to his domestic situation, Helen is tucking Bob in for the evening with nothing less innocent than Winnie the Pooh.

Mark has the traditional inappropriate conversation with Bob about who Bob prefers as parental figures, saying he doesn’t like it that Mummy prefers Heinrich. Helen helps with housework and can be seen quite symbolically cleaning up the meat grinder left in the kitchen yesterday. She reveals that Bob has been screaming for no reason in class lately. Mark, desperate, admits that he feels wrapped up against his will in a “war against women.” Zulawski, as much as he is sometimes labeled a misogynist, very fairly gives Helen the last word, and the more respectful and mature one, in this conversation: “There is nothing in common about women except menstruation… together we can listen if Bob cries out.” They lie naked in bed together, and she makes Mark the offer that they don’t have to make love… an offer someone only so recently, and painfully, romantically separated could appreciate. Sex is not the important thing here; sleeping together is.

Of course, Mark is not allowed his idyllic escape anymore than Anna is; in the middle of the night, Bob wakes up confused, screaming for his mummy. Helen realizes it was inappropriate of her to stay over, and they share only an awkward silence as Mark drops Bob off for school the next day.

Next, Mark is told the detective trailing his wife never returned. He is asked if he has been to the mysterious address himself. In a sad statement, Mark says the part of him invested in following Anna was “Pure blind ambition. There’s nothing ambitious left in me.” The second hired detective follows the trail to the building.

When detective number two arrives, Anna is found scrubbing the floors of blood in a scene reminiscent of Lady Macbeth. Detective number two starts to interrogate Anna about the disappearance of detective number one. This time, Anna is much less fearful, Once again, it is hinted that the monster has a divine presence, and that Anna is drawing strength from it. “I’m not scared,” she says. “Darkness is in your soul,” but he “promises so much comfort after the pain.”

When detective number two enters the room, the monster has a much more humanoid, and phallic, appearance. What appears to be blood and semen is pooled at the floor. “He’s very tired,” remarks Anna. “He made love to me all night.” Detective number two tries to shoot the monster, but Anna beats him over the head with a bottle of milk (again, symbolically) until he is monster fodder.

Cut to Mark watching what appears to be Heinrich’s video tapes of Anna’s dance classes. Dance instructors are known for being harsh (Black Swan, anyone?), but the implication of these tapes is that something “other” possessed Anna in the end—she makes a student hold a position of intense agony until that student bolts out the door, and then Anna performs a hysterical monologue for the camera about “two sisters, faith and chance” not too dissimilar from Robert Mitchum’s famous monologue about hate and love in Night of the Hunter. “Faith can exclude chance,” rants Anna, but “chance can explain faith–faith didn’t allow me to wait for chance.” She concludes, “I am the master of my own evil,” which is the reflection of goodness. My speculation is Anna is wrestling with the inner spiritual conflict all those who commit infidelity must grapple with—the chance of a lifetime to fall in love came at exactly the wrong time, when she was already in a committed relationship. Her absolute faith in her relationship with the spiritual being didn’t “allow her to wait” for the right time, so she had to take control of her destiny, and her own sin.

Cut to Anna back at the homestead, taking more possessions. Mark confronts her more steadily this time, asking her to wait until Bob isn’t around, accusing her: “You’re not as strong, or sure, of yourself as you thought you were, you keep coming back. When you’re there you want to be home, and when you’re home you want to be there.” Anna is quite literally wrestling with her own body at this point — Mark asks her to sit still with him, and she cannot stop fidgeting and fighting with her very own limbs in an eerily madcap, DR.-STRANGELOVE-esque manner. Anna refers to “two sisters too exhausted to fight anymore, both tearing at me, waiting to see who will die first.” I believe this can only be read as the sisters “faith” and “chance” Anna referred to in the video earlier.

Cut to Anna standing in a pleading position beneath a Jesus statue, perhaps the most explicit reference yet to the fact that her plight is spiritual in nature. For an uncomfortable amount of time, the viewer looks down on her, her guilt and desperation written plainly on her face, in a position to cast judgment on her. Then the camera zooms away for a long panning shot of Anna running out of the church and toward the subway to begin one of cult cinema’s most notorious sequences.

I have heard the more significant difference between the cut and uncut version of the film often come down to this scene shot in the corrdiors of the Berlin U-Bahn, which infamously taxed Isabelle Adjani. Apparently Zulawaski’s one stage direction for this inspired piece of emotional pornography was to tell Isabelle Adjani to “fuck the air” (as told to Tom Huddleston in a Time Out review). There is a part where Adjani’s head makes a sickening audible thud hitting the wall. Zulwaski claimed that he put her in a trance before shooting the scene, using techniques he learned from the avant-garde Polish director Jerzy Grotwoski, so she was unable to feel any pain. “She never felt anything because she went through these exercises in trance before the film, and she used it. Yet she used it in a very conscious way, she always knew what she was doing. It’s impossible to hurt yourself when you go into this.” (quote from Zulawski ‘s interview with Bird and Thorwer.) In the uncut version, Anna seizes up, screams in terror, and flings her body against a stone wall for a number of minutes, then bangs a grocery bag containing what appear to be milk and yolks against the wall, before collapsing and rolling around in the fluid on the subway floor while leaking what appears to be blood, milk, semen, and possibly other fluids from more than one bodily orifice. This scene has been read many different ways by many different critics, but I believe, once again, Zulawski is not as ambiguous as all that; I believe he explains this disturbing sequence in the very next scene, to those paying close attention (and still following the film’s bizarre logic at this point).

Isabelle Adjani, under a trance, “fucks the air” in the Berlin U-Bahn. POSSESSION.

“What I miscarried there was Sister Faith,” an exasperated Anna explains to Mark. “So what I must protect is Sister Chance.” In most literal terms, Anna has lost her faith in love, and is now only relying on the chance encounter that brought her to love the monster she now must give everything to protect–she has already sacrificed everything. It is here where she and Mark begin their most honest conversation about the destruction of their relationship. Mark explains how when he was a child he observed a dying dog giving its last yelps in terror, and he felt for the first time he was observing something real. Seeing Anna in her barest, most real state is vulgar to him in the same way.

Soon we see Heinrich at Anna’s love nest, trying to seduce her with an exotic French aphrodisiac powder. Of course, once they reach the bedroom, the monster manifests itself in its near-final, almost-human state, with eyes and a mouth. “What is it? Is this a joke?” Heinrich stammers. Anna reveals a fridge filled with body parts of the two detectives, the monster’s other victims, and begins to cut Heinrich, taunting him, “You are not different than anyone else…different bodies.” Heinrich flees in terror.

Cut to Mark playing airplanes with Bob. Heinrich calls Mark in terror, and Mark decides to come to his rescue. Conveniently, Margie comes to watch Bob, but faints dramatically in a quick cut once she arrives on the scene, perhaps underscoring the abrupt transition in a darkly comic manner.

Mark soon finds himself the latest man drawn to Anna’s hiding place for her secret lover. He discovers her horrors one by one, the flies, the decay, the fridge of body parts, and gasps for air. He notably takes a gun and turns on the stove before leaving for meeting Heinrich at the bar next door.

In their final showdown, Heinrich tries to convince Mark of the monster’s existence. Mark gets a chance to gloat at his competitor, basically telling him its his turn to suffer, before murdering him in the basest way possible, by drowning him in a bar toilet with his own aphrodisiac drugs.

Mark proceeds to light the fuse that blows up Anna’s love nest, to the laughter of a crazy passerby, then bolts away on his motorcycle to home. There he discovers Margie bloodied up and dying at their place, and, inexplicably, Anna safe in their bedroom. He cries in disbelief as she washes him up and removes his bloodied clothes. This is the last tender moment the viciously separating couple shares before they let go of each other completely. She looks at him, kisses him, and asks him, “Do you believe in God? It’s in me.” She kneels before him and makes her final offering, for old times’ sake, and while he makes love to her she looks away, possessed, afraid, already belonging to something beyond the both of them.

After they have wrung the last moment of love from their union, it is explained that Anna was forced to kill Margie because she was also trying to take the beast, or Sister Chance which must be protected, away. Mark explains to Anna, poetically, that his vision of God still lies in the yelp of the dying dog, or in the “branch of the eucalyptus tree.” However, he is so devoted to following his lost love as far as he can that he agrees to help her protect Sister Chance by disposing of Margie’s body.

It is after undertaking this horrific task that Mark himself returns to the monster’s site, which should have been torched, and follows the sounds of lovemaking up its spiral staircase to find his wife in the arms of the monster. The beast, now a nearly fully formed humanoid with tentacles, resembles Mark in body size and mop of hair, and Anna exalts over it the proclamation, “Almost….”

Here the narrative takes what must seem an odd digression as Mark visits Heinrich’s mother. However, I truly believe there are no unnecessary scenes in POSSESSION. All players in this nightmarish drama must answer to their sins equally, and here is where Mark must answer for Heinrich’s murder. Heinrich’s mother, surrounded by Catholic imagery such as the cross and the last rites, explains to Mark that she had to support her son, even though he himself already had a wife. “I had to like both of them,” she explains; that is the mother’s burden to bear, to always forgive a son, as any good mother-in-law on the other end of infidelity will tell you, especially a Christian one. She then muses that she can’t decide which is the worst sin: to “take away someone’s wife, to hurt a child, or to kill.” Mark, of course having killed now, may have possibly committed a worse sin that adultery, in other words. Heinrich’s mother drinks reflected in a mirror as her final last rite, and reposes in her bed in such a way that it is perfectly clear she has lethally poisoned herself, claiming she cannot live without Heinrich.

Now the people who have been spying on Mark the entire film—the very people he used to work with—come out of the woodwork to surround him. He left his career to focus on his family, and clearly that was the wrong move, as now there is nobody else to take care of the drowning world—it is his responsibility, and the apocalypse is quite literally about to happen because of his neglect.

What ensues next can only be described as a balls-out action sequence, done Zulwaski-style. Mark rides back home only to find the police have staked it out; he crashes into the police car purposefully, rolls out of the car and sprints away. The police shoot, and he shoots back. Mark bolts away on his motorcycle, quite literally crashes at Anna’s love nest, and climbs the spiral staircase. The spies start to follow his bloody trail up the stairs.

At one point, Anna appears beside him with the completed beast, who is now Mark’s exact doppelganger. “I wanted to show it to you,” she explains. “It is finished now.” Just like Helen, this form is an exact mimic of Mark except for the green eyes, the passion crossed with rejection of the heart, in perhaps a sad statement of how we often set our next partner up to either fit or eclipse the role of our previous romantic ideal, hoping not to repeat all of our same mistakes. Mark makes a move to shoot Sister Chance, who now looks exactly like Mark. Anna is shot, and Mark is shot by his pursuers below. They share one last bloody kiss before Anna, in a beautiful visual metaphor, quite literally shoots herself in the back.

Sister Chance, now the mimic Mark (notable because of the green eyes), continues what has now become a comic, cosmic battle up ever-ascending stairs. He actually shouts in exasperation at one point, “Is there a way out?” while he climbs over a woman poised as a gatekeeper at a desk and has her shoot down at the spies. One of the spies ascending the stairs bends over to pull up his sock—revealing himself as the acolyte in the pink sock, Mark’s successor, further emphasizing the circular nature of this whole relentless hellscape.

In the final shot, Helen and Bob are sharing a quiet domestic moment in Mark’s old home. It is revealed that this is the door Sister Chance is banging on at the top of the stairs, programmed to enter a life of normality and to pursue his destined imitation mate. Bob, sensing the man knocking on the other side is not the same man as the father he once knew, screams in terror, “Don’t open, don’t open!” and flings himself facedown in terror into the bathtub rather than face the monster, while apocalyptic sirens, bombs, and flashes of light detonate outside the door. A terrified Helen stands at the door, debating whether or not to open it for this new, shadowy figure, while the haunting swells of Andrzej Korzy?ski’s main theme for POSSESSION, a swelling piano score that would sound anciently classically beautiful if it wasn’t for how off-kilter it was, raises to a fever pitch. Helen’s green eyes, the same as the eyes of Sister Chance, are the final focus; remember, in Zulawski’s own words, representing the color of passion mixed with the color of rejection of the heart.

— SHARON GISSY.

Tags: Andrzej ?u?awski, Andrzej Korzy?ski, Bruno Nuytten, Film Reviews, Frederic Tuten, Heinz Bennent, Horror, Isabelle Adjani, Long Reads, Psychology, Sam Neill

No Comments