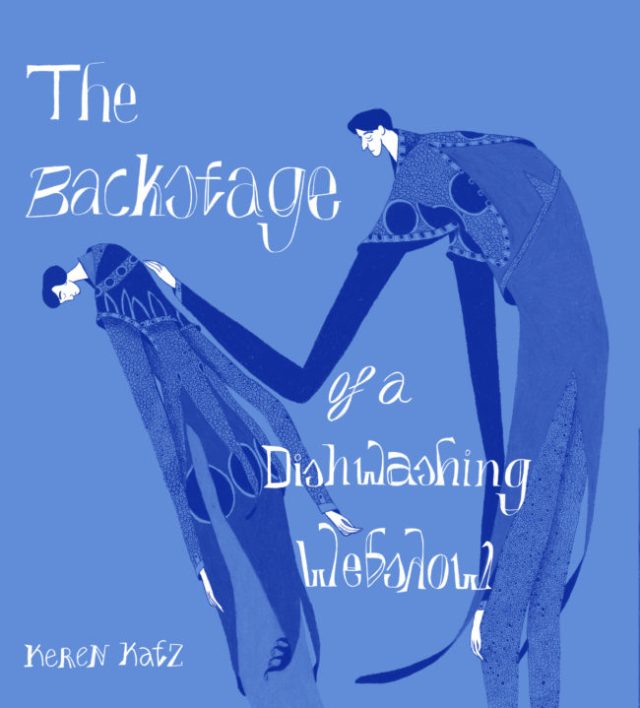

As far as studies in contrasts go, you could make a pretty compelling argument that cartoonist Keren Katz’s latest book, The Backstage Of A Dishwashing Webshow, is precisely that: Matter-of-fact, minimalist text (and even more minimalist dialogue) juxtaposed with and/or against kaleidoscopic, fluid, complex, symbol-laden artwork that eschews borders and panels because it simply can’t be contained within them, either physically or conceptually — but a few pages in is all it really takes to disabuse you of that notion at least partially, as it’s the interplay between the two that lends this entire work the distinct flavor of a “tone poem,” albeit one cleverly disguised as a linear (enough) narrative. Possibly.

Released around the middle of last year by Secret Acres, it’s taken me this long to get around to reviewing this one simply because it’s taken me this long to really absorb it in its totality — and, truth be told, I may not even be “all the way there” yet. But given that’s actually one of this comic’s strong suits (and we may as well just admit that the term “comic” is applied very loosely in regards to this work) — its mysteries both overt and subtle never confound per se, but they absolutely do demand re-analysis and re-interpretation around any and every corner — I feel as qualified as anyone else (or at least as qualified as I’m ever likely to be) to provide my thoughts on both the book itself and the, at the risk of sounding like a complete asshole, journey it took me on.

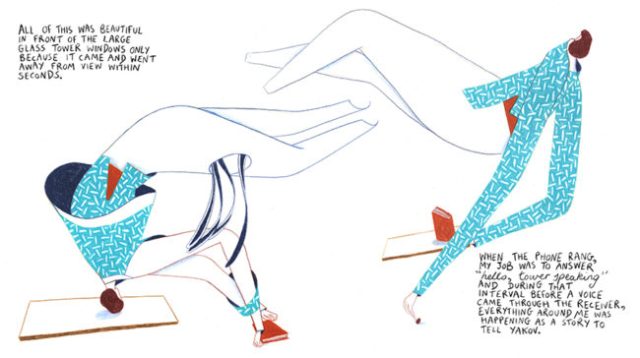

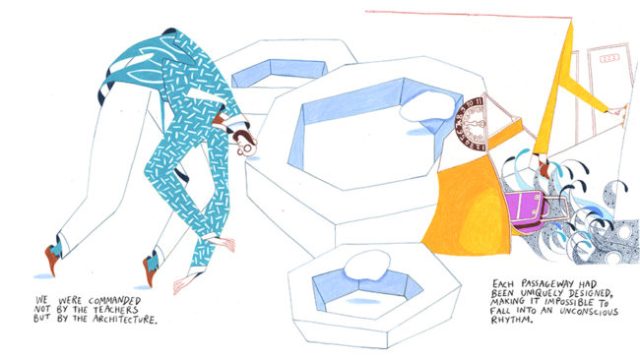

Not that corners are, in and of themselves, much of “a thing” herein: The imagery is open, fluid, dynamic in ways that nearly defy description, its color patterning and texturing lending to it much the same feeling as collage; of disparate elements and even media coalescing into an overall picture that is, if you’ll forgive the term, jumbled, but nevertheless communicates itself to itself — and to readers — in singular, and undoubtedly holistic, fashion. And even though the vistas and expanses Katz brings to life and that can unimaginatively be labeled “locations” change (from a Broadway theater/prop storehouse in the prologue to an air traffic control tower in the early going to the intentionally-vague Mount Scopus Academy — a school that teaches “the art of transmutation” — and its apparently-mountainous environs for the bulk of the story), the aesthetic and ethos that Katz establishes immediately is sustained throughout regardless of shifts in her “playing fields.”

Which I guess, in appropriately roundabout fashion, brings us to that occasionally-dreaded “meta” label — one that applies here not only because the book is almost breathtakingly self-referential, but because it appears to be shot through with autobiographical elements, as well, Katz’s protagonist, Rivi, echoing not so much direct experience from her creator’s own life, but direct perceptions and interpretations of those experiences, or even of life and its living in a more general sense.

Consider nominal love interest Yakov, with whom Rivi had a long-distance relationship during her time as an air traffic controller, and who later re-appears as her next door dormitory neighbor at Mount Scopus — unless it’s not actually him, but just some guy who shares his name. That’s never really clear, nor is it ever really clear that it actually matters all that much. In due course, he finds himself in love, albeit at a remove, with Rivi’s roommate, Novak, anyway — host of our titular dishwashing webshow (an actual phenomenon, by the way — I looked it up and found myself bored to tears in just about no time). And while all of this would be complex enough in and of itself, no question, when you factor in Rivi’s relationship with her own father, who at the very least serves as a kind of subconscious template for the kind of man she’s looking for (“looking” being the operative term here — “finding,” after all, leads to an entirely new set of complications), things get even stickier, even trickier, even more uncomfortably psychoanalytic.

Now, I realize full well that I proposed that this was a linear text at the outset, and so it is — but that doesn’t prevent it, admittedly unbelievable as it may sound, from being an elliptical one at the same time; like dual tributaries running out of the same ultimately unidentifiable source, Katz’s narrative “streams” converge, go their separate ways, and come back together in unpredictable and quietly fascinating fashion, accentuating her theme of life forever changing, but the people living it returning to familiar places, mindsets, patterns of behavior, modes of existence. “The more things change, the more they stay the same” is selling the core concept here too short, though: Katz seems more to be advancing the argument that the more things change, the more we stay the same. Even, possibly, when we don’t.

Which would be as good a place as any for her to make broad genuflections in the direction of the old “nature vs. debate,” but art has already been there, done that, too many times to count. Pre-destination — or, at the very least, its less soul-crushing and onerous cousin, pre-determination — aren’t engaged with directly, but hang over these proceedings in Sword of Damocles-fashion nonetheless, omnipresent by dint of their sheer silence, their intractability, their ineffability. But as with all things that carry legitimate conceptual weight and power, that weight and power lies in their ability to command and control all without a word or gesture or action: They are there, and that’s enough. Sometimes it’s even too much.

That doesn’t prevent Katz from prodding them at the margins, though, another of her book’s delicate acts of interplay, of push and pull, of unstated but unmistakable (at times borderline-unbearable) tension, the spaces between the polarities she limns doing double-duty as both formless void and raw, tightly-wound nerve. When it all ends — or at the very least stops — we’ve likely come back to the beginning, in a manner of speaking, but we’ve explored spaces and regions scarcely imagined, much less seen, before, and we are not the same. Except for the fact that we are. And that’s both scary as hell and oddly comforting in equal measure.

Tags: Columns, Comic Books, Comics, Keren Katz, Secret Acres

No Comments