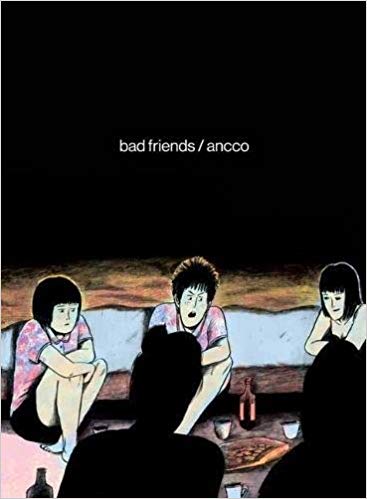

Growing up is hard, whoever you are — but odds are that no matter how hard your adolescent years were, they weren’t as hard as Pearl’s. Or should that be Ancco’s?

Precisely how autobiographical Bad Friends is seems to be a bit of an open question — the book (originally published in Korea in, if I’m not mistaken, 2012, and finally released in an authoritative English translation by Drawn+Quarterly just a few months ago) has all the character and authenticity of memoir, but I’m open to the possibility that certain incidents/elements may have been altered (and by that I mean “toned up” or “toned down”) for dramatic effect, logistical purposes in relation to narrative flow, etc. Still, whatever the case, and whatever the nature of Ancco’s choices, they indisputably work, and make for one of the more compelling, if disturbing, reads in a very long time.

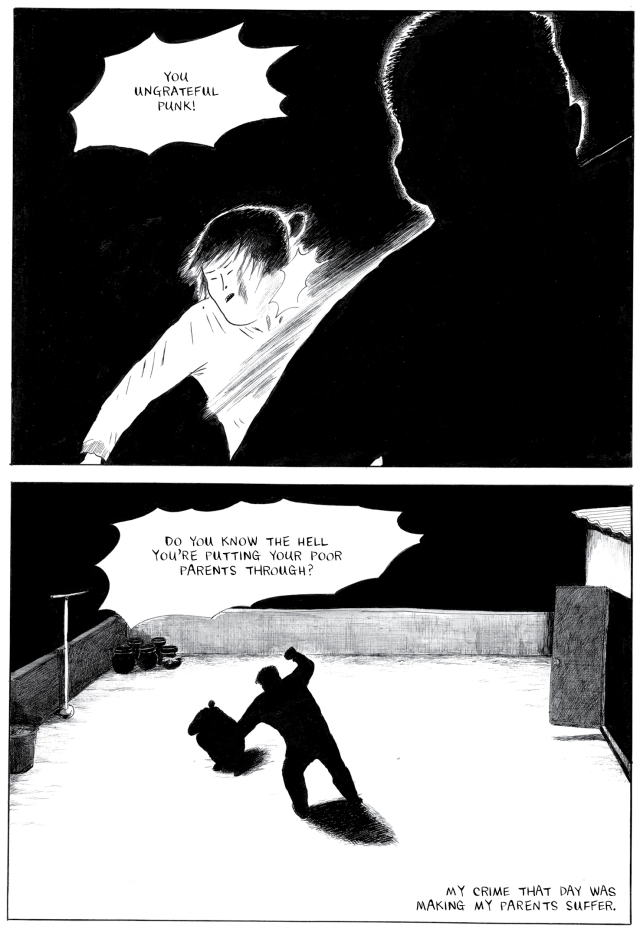

Ancco’s protagonist/stand-in, Pearl, is an immediately absorbing character, displaying an admirable streak of rebellious independence in the face of all odds — physically abused by her teachers, fellow students (mostly older ones), even her father, no one would blame her in the least for curling up in a shell of pained introversion, but instead she expresses her individuality as stridently as possible. That doesn’t always lead to smart choices, as you’d no doubt expect — running away from home makes a fair amount of sense given her family situation, quickly falling into potential employment at a brothel decidedly less so. And that’s only one example of a small series of ill-informed decisions.

Some of this could, I suppose, be blamed on her best friend, Jeong-Ae, if one were to take the easy, knee-jerk approach — but Ancco, to her credit, does no such thing, instead showing how the two girls form something of a co-dependent bond, sometimes for good sometimes for ill, as they navigate the landscape of “teenage-hood” in a 1990s South Korea having something of a societal identity crisis of its own, torn between tradition and a distinctly Westernized encroaching modernity, the effects of this unspoken conflict exacerbated by a rough and prolonged economic downturn. It’s a hard time to be having a hard time.

It’s generally the outer circle in this clique of friends who are the “bad” ones, but even there, Ancco goes to great lengths to express her/Pearl’s acknowledgement that many of them possess qualities that help to facilitate her own eventual emotional, psychological, even physical survival. Ditto for her father, who is violent and frightening in the extreme, but is shown to be less a monster than a man in profound pain who only knows how to expunge it through his fists, and always to his later detriment. This kind of nuanced characterization is honest, sure, but more than that it’s brave, as drawing people in broader strokes would no doubt lead to a story with far greater “lowest-common-denominator” appeal and a larger commensurate payday. But Ancco never takes takes the easy way out, and we’re all the better for it.

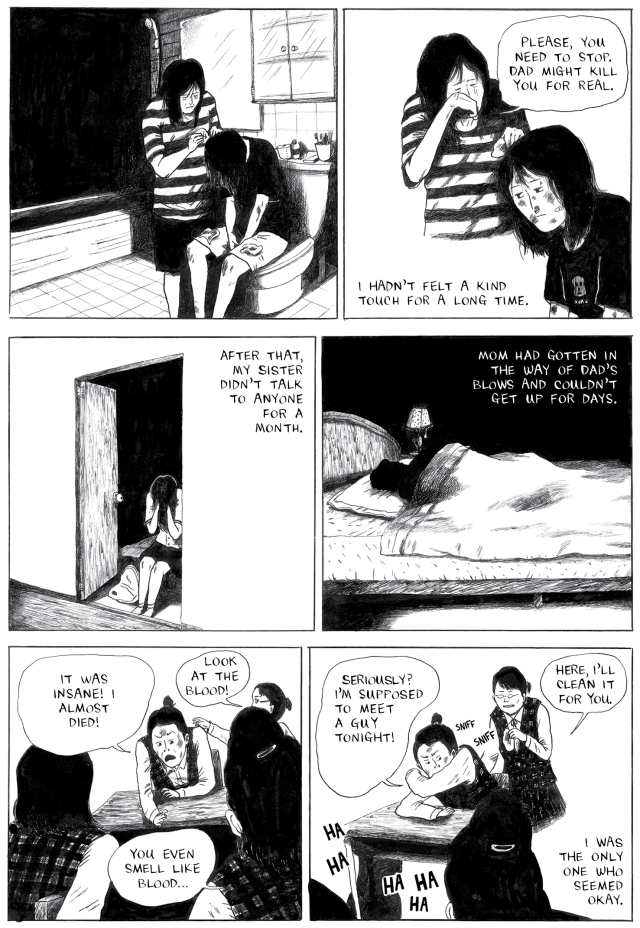

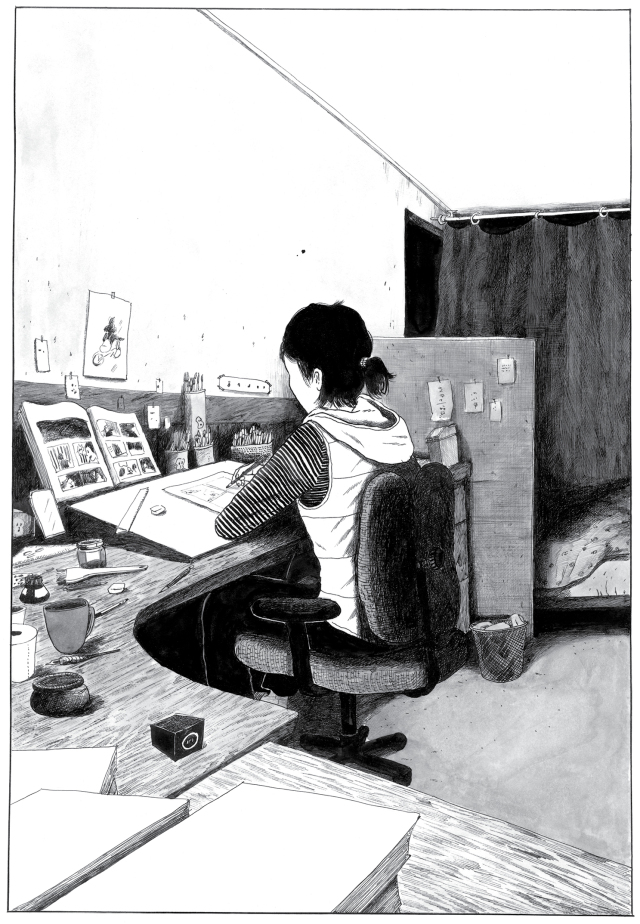

And speaking of drawing in a more literal sense — damn, Ancco’s cartooning skills are quite literally above reproach and uniformly stunning from page to page, whether those pages revolve around quiet introspection or sudden, shocking, visceral attacks. Her fine, detailed line is precise yet in no way clinical, maintaining and amplifying the emotional through-line of each scene in a way that many technically exacting illustrators seem to manage to lose in their quest for “perfection,” and as a result the connections between past and present, the thematic precis that our growing up not only shapes who we eventually become but remains an inescapable part of our essential human core, comes through not just in the book’s tight, rhythmically-paced script (although, in fairness, a couple of turns of phrase left me scratching my head — but translator Janet Hong is known to be one of the best in her field, so what the hell do I know?), but in the art, as well, every panel communicating not only the requisite key information about what’s happening in the outer world the story takes place in, but in the inner world each character inhabits, as well.

Circling back to where we started, then, yeah, growing up is hard — but the girls in this book manage to pull it off. They don’t emerge from adolescence unscathed, and the scars they carry inside and out go some way toward defining the trajectories of their lives, but Ancco’s skill at stepping back from the precipice of utter despair, her firm belief in the idea that not quite all is lost even when it looks to be, proves to be the one inch of blessed relief that sees Pearl and her not-entirely-bad friends through — even though there is a key loss along the way, one that haunts them all and hangs, unresolved, over everything. I’ll say no more other than that it’s probably not what you think (as in, it’s not a death), but it does serve as a more-than-bittersweet example of how difficult it is to follow through on youthful dreams and ambitions to become something and someone more than our socio-economic status steers us toward.

All told, then — not that you haven’t picked up on it already since I know damn well you folks are smart — Bad Friends is a legitimately remarkable work of comics art in every sense. It’s a book you’ll return to again and again, not because it’s comfortable, but because it’s undeniable. It’s a story that had to be told, and had to be told exactly as Ancco relates it here. It’s the very definition of — and this is a term I employ very sparingly — a masterpiece.

Tags: Ancco, Columns, Comic Books, Comics, Drawn+Quarterly, Janet Hong, South Korea

No Comments