The name Gerald Jablonski is one that few people know, but everyone should — not that he probably cares either way. Jablonski’s comics career began in 1976 with a single strip in the pages of Bill Griffith and Art Spiegelman’s Arcade #6, and then — nothing. He was literally the perennial “one-hit wonder” until 1990, when he suddenly decided to give the whole “comics career” thing another go, first with a strip in Snarf, then with further material appearing in anthology titles like Tantalizing Stories and Buzzard before Fantagraphics finally gave him a one-off book of his own, Empty Skull Comics, in 1996. And then things got kinda quiet again for the most part.

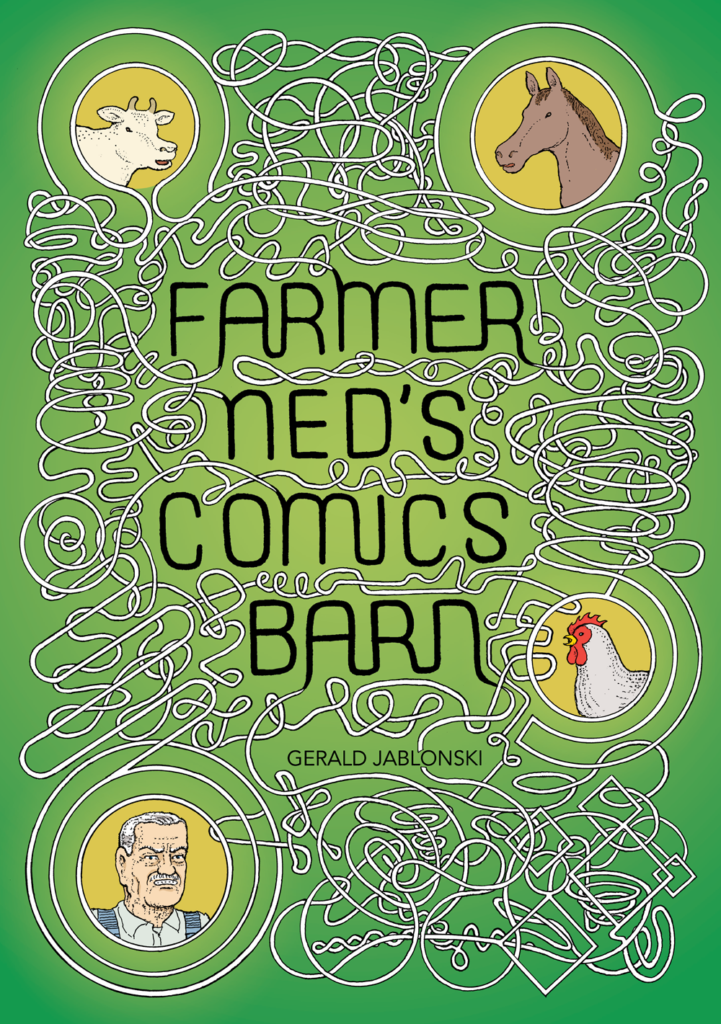

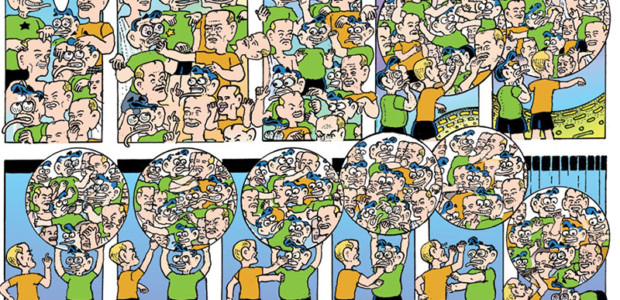

Fast-forward to 2002 when, thanks to a Xeric Grant (remember those?), he was able to self-publish the first issue of Cryptic Wit, a (very) semi-regular solo title that saw further installments unleashed on an undeserving public in 2008 and 2012. Obviously, then, “prolific” is something the esteemed Mr. Jablonski is not, but what he lacks in quantity he more than makes up for in quality. There’s just one problem with all of the publications his work has seen print in — they’ve never been big enough. And I do mean that in a strictly dimensional sense, rather than in terms of their length. Jablonski’s strips are so intricately-detailed and tightly-packed that the standard comics page — heck, even the magazine-sized pages of Buzzard — could never do them justice. Thankfully for us all, that problem has finally been solved thanks to Gary Groth’s “Fantagraphics Underground” sub-imprint, which has recently released the first, comprehensive, full-color collection of Jablonski’s work, entitled Farmer Ned’s Comics Barn, in a glorious 9 1/2″ x 13 1/2″ format, so at last we can see 100 pages of what this enigmatic talent has to offer without having to strain our eyes. Thank you!

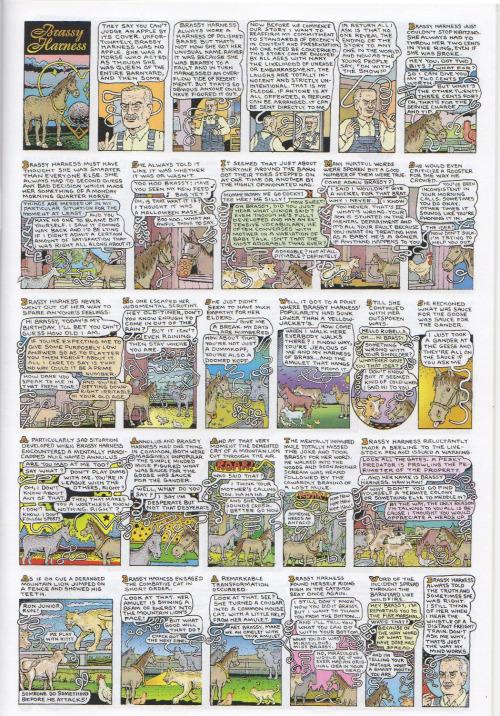

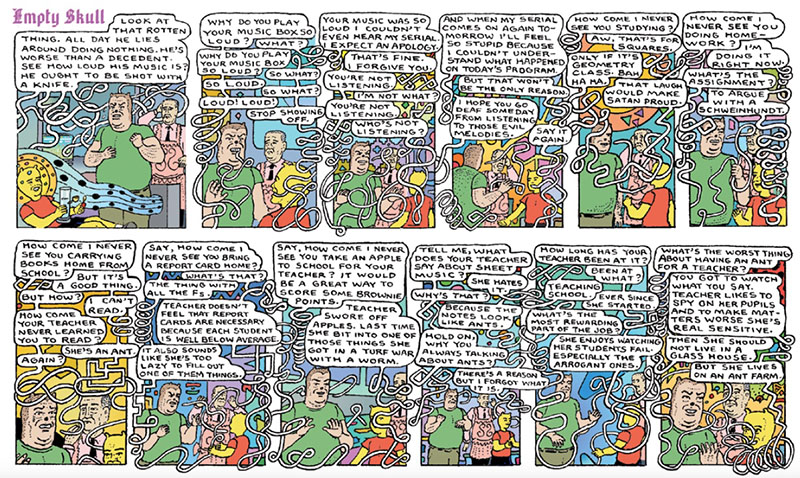

To the extent that Jablonski’s comics are “known” for anything, it’s for their signature looping, twisting, spiraling word balloon tails. Seriously, they’re a veritable maze trailing from the mouths of their speakers, but as singularly bizarre as they are, they pale in comparison to the mind-bogglingly surreal contents of his (always one-page) strips themselves, which generally fall into three distinct groups :

- The “Farmer Ned” stories begin with their eponymous narrator either lamenting the state of the world today, completely over-hyping the significance of the yarn he’s about to relate, or both, before cutting to a scene of a smart-assed young calf giving its mother a hard time and then following the travails of a disruptive newcomer to the farm (usually, though not always, a horse) who proceeds to work the nerves of every other animal around until the story not so much ends as simply stops;

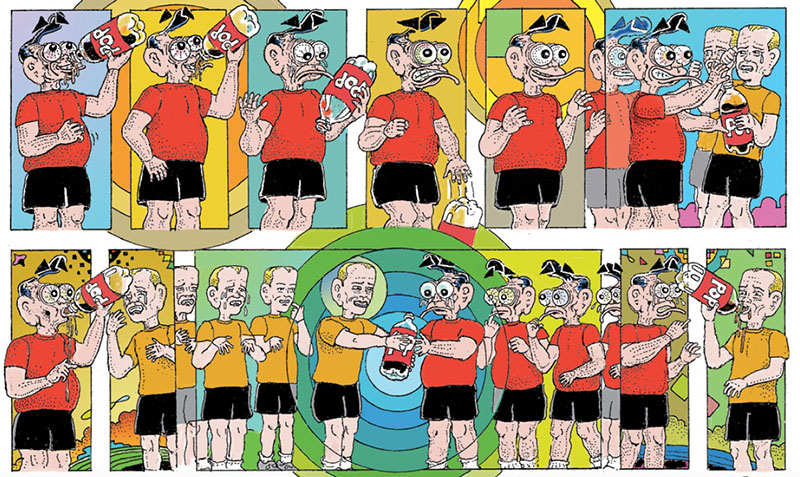

- The “Two Kids” stories delineate the wordless psychedelic violent confrontations between a youthful Ronald Reagan doppleganger and a youthful Gerald Ford doppleganger in a manner that can only be described as “Spy Vs. Spy on bad acid”;

- And, finally, the “Howdy And Dee Dee” stories follow the exploits of a midlife, bear-faced “man” and his yellow-skinned, dog-eared nephew, who’s always playing his favorite band, Poopy, so loud that his uncle can’t hear his favorite radio serial, which inevitably leads to a series of vaudevillian insult trade-offs, followed by the nephew complaining about his teacher, who is an ant, and the arrival of a third figure, a friend of Dee Dee’s who looks vaguely like Tony Randall and never says a word. He does, however, wear a pink apron and look pained and/or constipated at all times. Again, these strips don’t really conclude, they just come to a stop, and their titles seldom, if ever, have anything to do with what’s happening on the page.

I’ll be the first to admit that the term “acquired taste” would be more than appropriate to drop into the proceedings as a descriptive at this point, but seriously — if you can’t get with this shit, it’s your loss. Jablonski’s comics are not only gut-bustingly hilarious, they’re also visually arresting on a level that’s almost impossible to conceive of until you see ’em for yourself. In his introduction to this volume, Jim Woodring reverently describes Jablonski as a true “lunatic,” and it’s no hyperbole — his vision is so well and truly singular that it could only come from a mind with no concern beyond emptying its contents onto the page in as authentic a manner as possible. The visual language they speak is so completely unlike anything else that it offers no evidence whatsoever its author has ever even seen another comic strip by another artist at any point in his life, much less bothered to develop an understanding of what his chosen medium “can” or “can’t,” “should” or “shouldn’t” do. Jablonski creates art for that rarest and most honest of all reasons — because he can and probably even must. The idea of an “end user” in the form of an audience doesn’t seem to enter into his thinking at all — you can take this shit or leave it, but it is what it is, and what it is certainly is nothing like anything else.

I’d say that I “love” this book, but honestly that seems too small a word with too narrow a set of emotions and reactions attached to it. In truth, I’m in awe of it, I’m perplexed by it, I’m amused (to no end) by it, I’m flabbergasted by it, I’m confounded by it, I’m fucking envious of the intellect it came from, and I’m amazed by the fact that I can be as constantly taken aback as I am by strips that play out in more or less exactly the same fashion every time. And maybe the best part of all is that Gerald Jablonski could care less what I think and he’s just gonna keep making the comics he wants to make in the way that he wants to make them, reaction to his work be damned. That’s integrity of a sort that’s almost impossible to come by in this day and age, and to which all I can say in response is — I don’t care how or when I die, just make sure I’m buried with a copy of Farmer Ned’s Comics Barn in my hands.

Tags: Comic Books, Comics, Fantagraphics, Fantagraphics Underground, Gary Groth, Gerald Jablonski, Jim Woodring

No Comments