Just about any and every artist that ever lived has been plagued with periods of self-doubt and creative bankruptcy, but the truly ingenious among them have found ways to use those dark times as inspiration — after all, if you can’t rise above it, why not explore it for all it’s worth? It seemed like every book Stephen King wrote for a good decade or more was about a writer who had hit a brick wall, and cartoonists like Robert Crumb and Joe Matt have literally built their careers around unflattering portrayals of what happens (or doesn’t happen) when their creative wellsprings run dry.

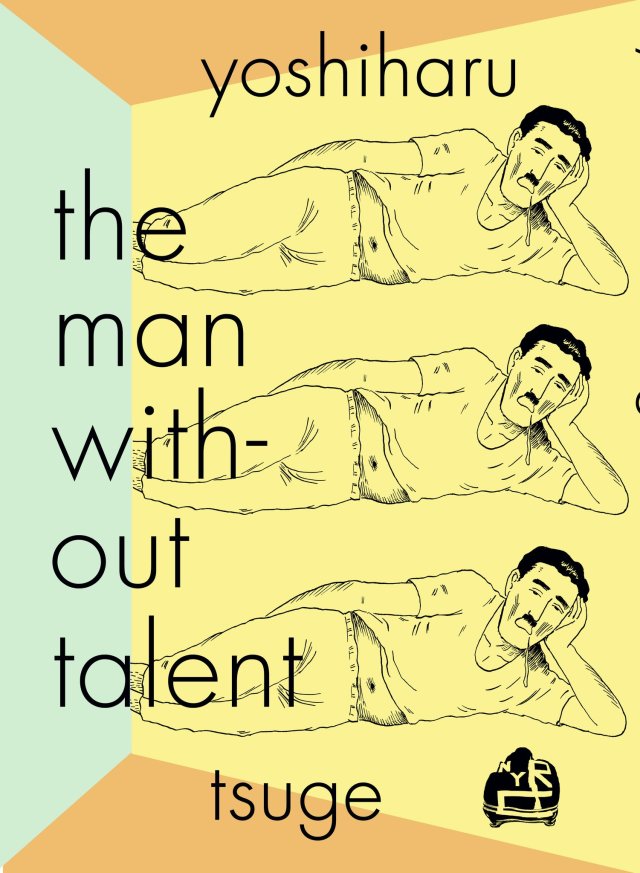

This is all minor-league stuff, though, compared with manga legend Yoshiharu Tsuge’s The Man Without Talent, the unflattering self-portrait to end all unflattering self-portraits, largely because it eschews any sort of overt plays for sympathy in favor of a raw, unvarnished, sometimes even dispassionate examination of an artist with no idea what to do next and little motivation to break out of his doldrums, opting for a life as a ferryman, camera salesman, and stone gatherer when he becomes frustrated with trying to create a new manga. There’s a little bit of distance between author and subject provided by dint of Tsuge’s decision to make his protagonist an obvious stand-in named Sukezo Sukegawa, but there’s clearly and obviously less than one degree of separation going on here, a fact which is crystal clear even if one doesn’t read the highly-informative afterword by translator/editor/manga “renaissance man” Ryan Holmberg — not that I’m suggesting you should pass on it, though, simply because if you know Holmberg, you know you’re going to double your reading pleasure (as well as your understanding and appreciation of the work in question) by taking/making time for his essay.

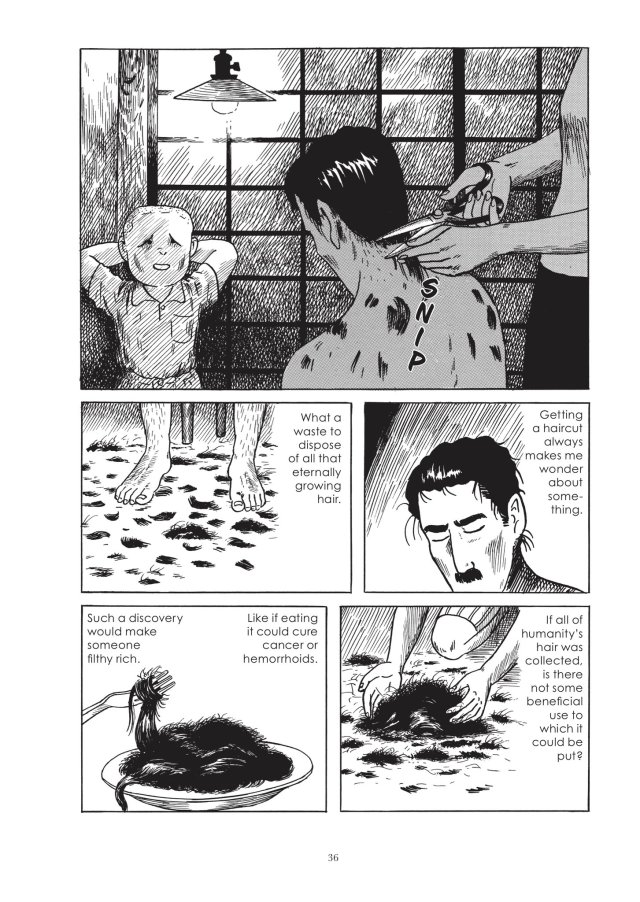

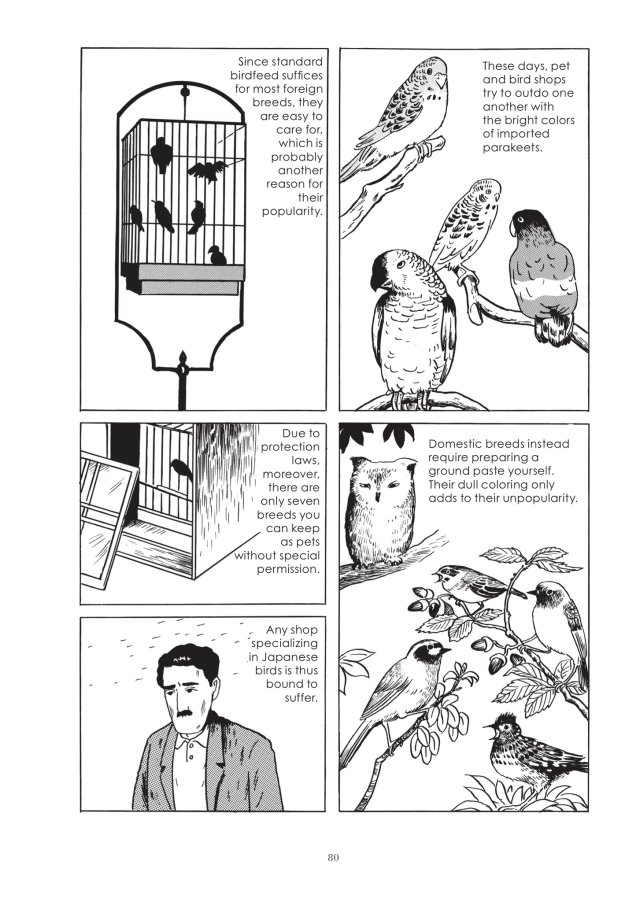

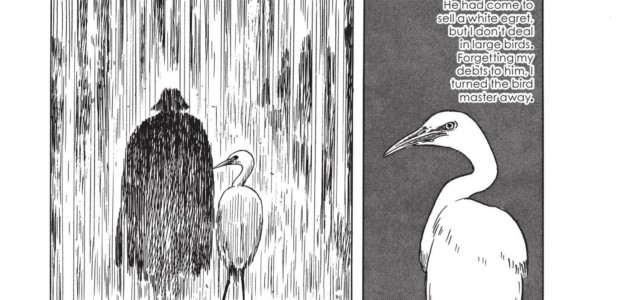

Still, skipping ahead to the end is bad form, and if you were to do that, you’d be delaying the immense joy of the story itself — and yeah, I just said “joy,” which probably seems incongruous at the very least given that we’ve already established that this is a book that portrays its own creator in pretty stark, and frankly pretty dark, fashion. The damned thing is, though, even when Sukegawa/Tsuge is at his most unforgivably self-centered — such as when he’s charging his beleaguered wife with handing out fliers promoting his work, or leaning on his youthful son to not only provide emotional support over and above the call of the duty but literally to serve as his only connective tissue with reality itself — there’s a kind of forlorn, poetic quality to it all, communicated not only by means of Tsuge’s no-frills writing, but also his crisp, detailed, borderline-cinematic illustration. The art herein, crucially, pays just as much attention to places and things as it does to people, and this gives the entire proceedings a distinctly holistic sense of time and place — one that I would think probably hits home even harder for those who were around in Japan in the early 1980s, which is when this was originally written, drawn, and published.

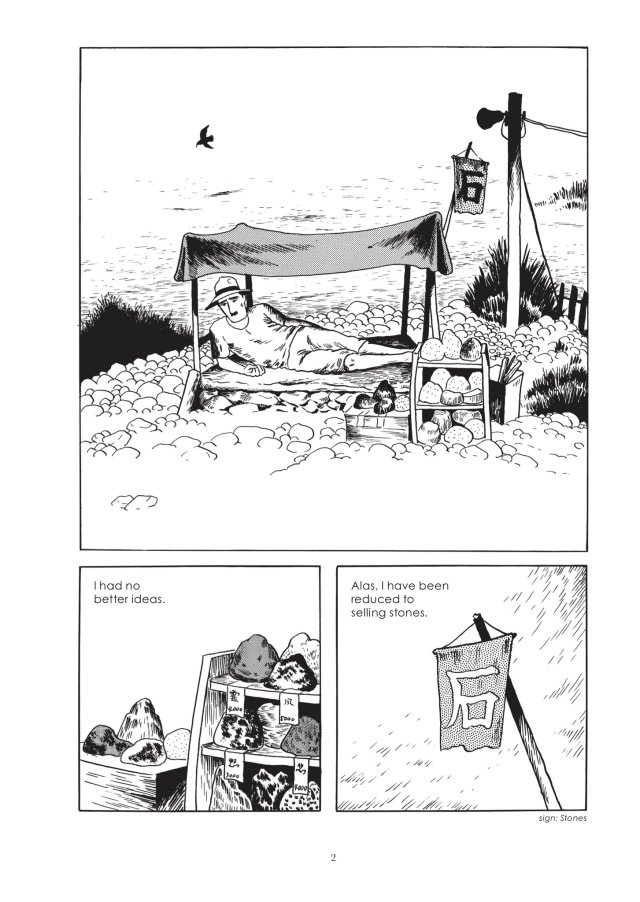

That being said, this certainly isn’t work that feels dated in any way, shape, or form, as the mental health struggles it depicts are, unfortunately, timeless, and also because Tsuge isn’t afraid to approach it all with a very subtle wink and a nod. As Holmberg’s essay makes clear, the biggest difference between author and stand-in is that he actually rather enjoyed plumbing the depths of his personal darkness, and quite likely engaged in more than a bit of creative license in his depiction of his wife as a constant nag and “himself” as a naive sucker floating from one brain-dead hustle (selling rocks? seriously?) to another, even as he yearns for a life of solitude and contemplation. He doesn’t flinch when it comes to drawing attention to his lethargy, stubbornness, or emotional illiteracy, but come on — is he really this bad? That’s a question we’re never given a direct answer to, and that approach makes the book invariably more interesting than it likely would have been otherwise.

This may read as a pretty dry text, then, at times, but there’s no doubt that Tsuge keeps his tongue planted pretty firmly in cheek throughout, and this makes even the book’s most harrowing moments — content alert, there’s a suicide attempt in these pages — come off as something rooted in autobio, but communicated with a fair degree of creative license. As you’d no doubt surmise, Tsuge’s gotta walk a pretty fine line in order to make this work, but work it surely does, as the end result is one of those rare diamonds in the rough that we’re each of us constantly looking for: a reading experience well and truly unlike anything else.

To the extent that Tsuge’s work is known in the English-speaking world, it’s mostly by repute, a situation which was also the case in regards to his younger brother Tdao, a “neo-manga” trailblazer who’s also finally getting his due on this side of the Pacific thanks in large part to Holmberg and publisher New York Review Comics — who are also responsible for this immaculate, immersive package. This marks the first time Tsuge has been translated into English, in fact, and while it’s obviously long overdue, it’s equally true that it was worth the wait, and it’s exciting to consider that it likely represents just the start, the opening of the floodgates, as Drawn+Quarterly has a collection of his short manga slated for an April release, as well. I’m “all in” for that — as should you be — but until then (and after), I fully expect to read The Man Without Talent a good few more times, and to come away from it more impressed with each reading.

Tags: Columns, Comic Books, Comics, japan, manga, New York Review Comics, Ryan Holmberg, Yoshiharu Tsuge

No Comments