I’ve often remarked — no, I swear, I have! — that the best cartoonists are those with no fucks left to give, but leave it to Casanova Frankenstein (or, if you’re old-fashioned, Al Frank) to prove me wrong: You see, he’s living proof that the best cartoonists are those who never had any fucks to give in the first place.

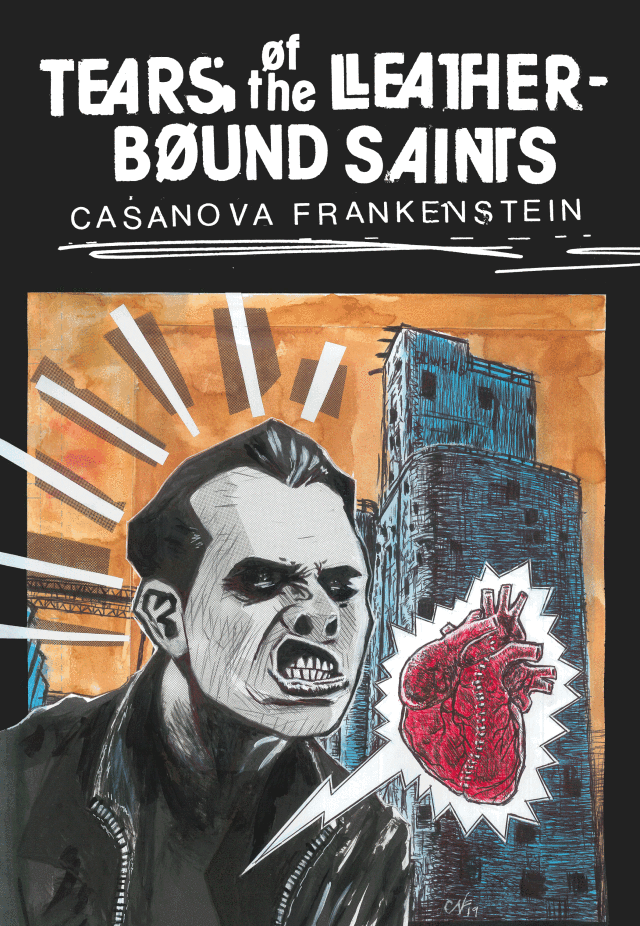

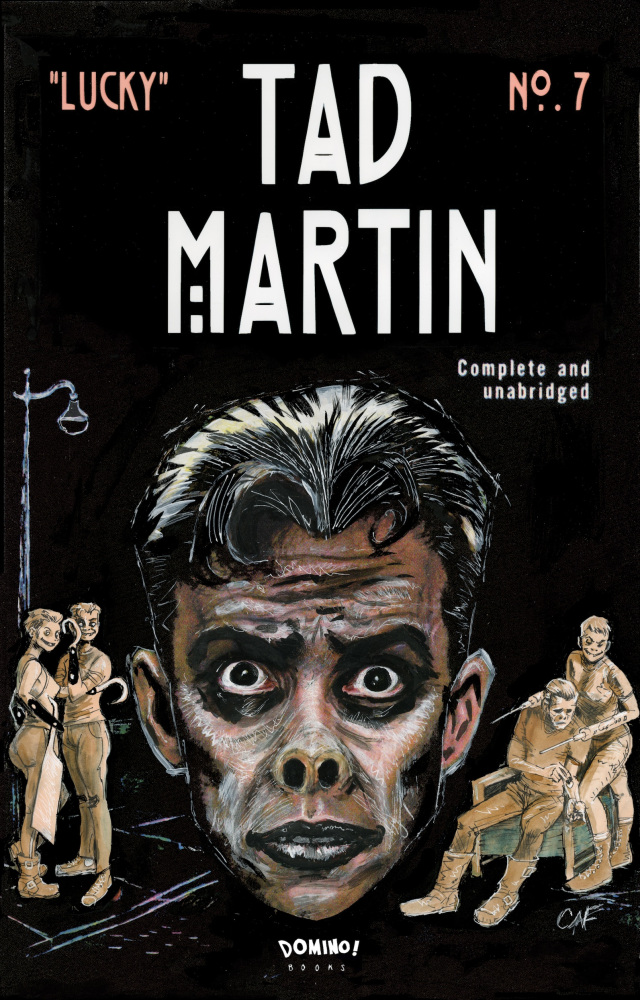

Long-time fans and admirers of Cassie’s Tad Martin work have suffered from an embarrassment of riches in recent years, beginning with Profanity Hill/Teenager Dinosaur issuing The Adventures Of Tad Martin #sicksicksix after nearly a two-decade publishing hiatus for the title, continuing through the artist self-publishing The Adventures Of Tad Martin Super-Secret Special #1 and, later, The Adventures Of Tad Martin Omnibus hardcover through Lulu, and culminating in Austin English’s Domino Books releasing the dreadfully gorgeous Tad Martin #7. In between all that, however, Gary Groth’s “street cred” imprint, Fantagraphics Underground, also unleashed on an undeserving world two purely autobio Frankenstein books, Purgatory and In The Wilderness, and their third release from the unofficial “granddaddy” of Austin underground cartooning, Tears Of The Leather-Bound Saints (officially listed in the copyright indicia as Tad Martin #8), falls somewhere between pure memoir and nightmarish hellscape, with little to differentiate the two thematically, even if the strips it presents — rotating as they do between those that feature Tad acting as stand-in for his creator and others that offer no such admittedly slight degree of removal — make it obvious. But, as you’ll soon see, “obvious” is probably not a word we want to use in relation to this comic, even when it applies.

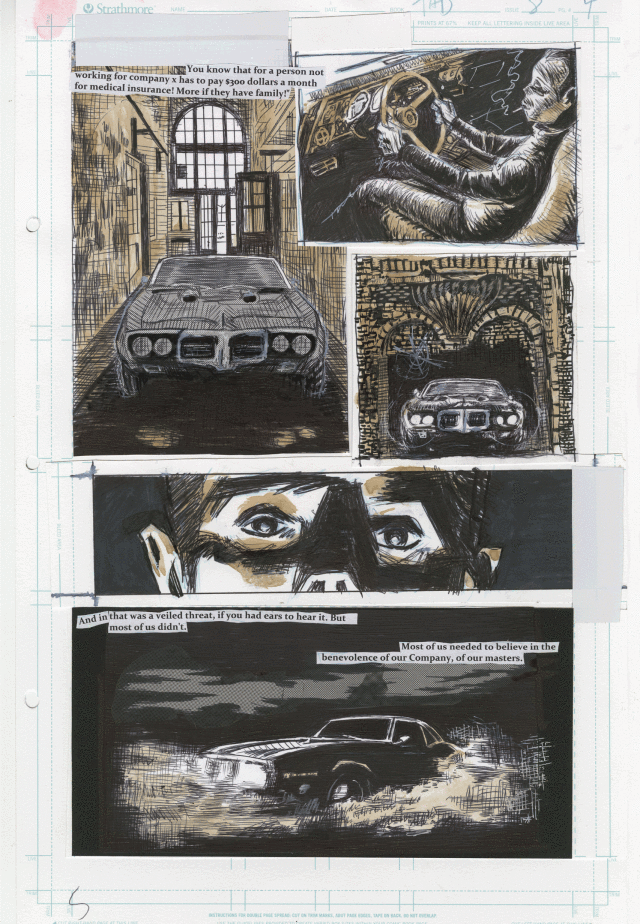

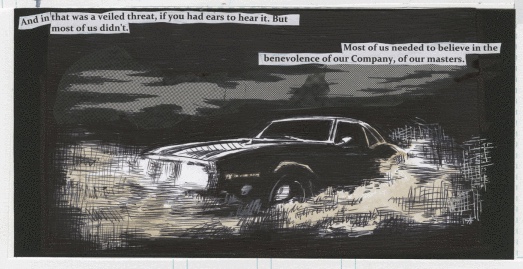

Every Tad release is a re-invention of both character and cartoonist, and that trend continues here, even if the “production art” ethos of Tad Martin #7 not only carries over, but is amplified and accentuated, and things like the signature black “muscle” car and nihilistic attitude are, of course, present and accounted for. This time out, though, our anti-hero’s nihilism is given breadth, depth, context, and meaning — after all, if you worked at a dangerous factory producing units of your own death with no regard to employee safety or labor and fair-wage standards (Frankenstein makes clear that this particular shithole isn’t unionized), you’d have it in for the world, too.

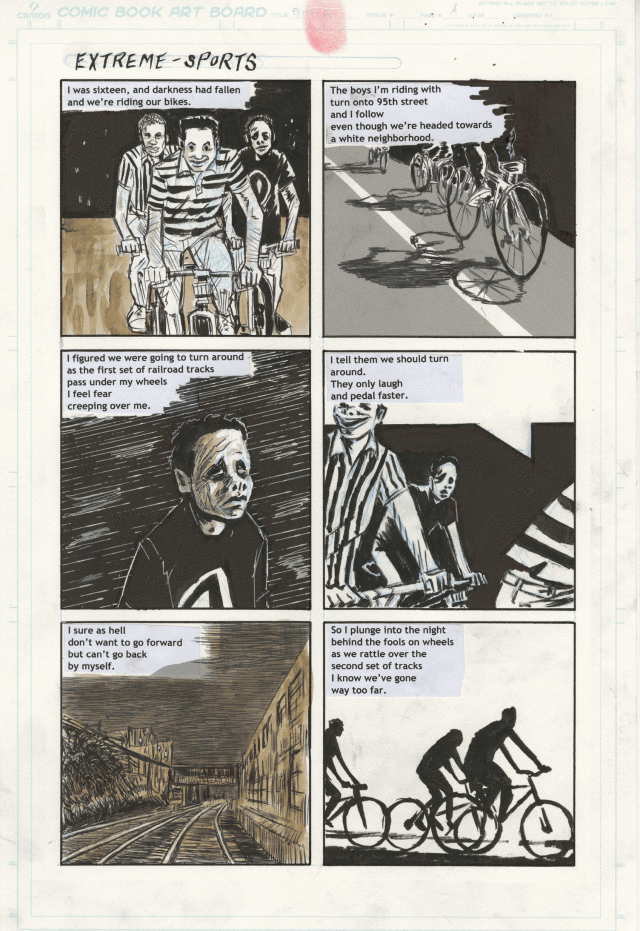

Which brings us back to the whole “no fucks to give” thing — Tad, this time out, is his author at precisely that point in his mind, while the “early days” strips are tasked with explaining how he got there. How whiteness and family and bullying and school pushed him down into a hole that only punk could help him climb out of — albeit gradually and, it would seem, temporarily, in fits and spurts. The cartooning came later, and when I piece that chronology together, that’s how I come to my conclusion that giving a shit was a well that had run dry on Frankenstein’s part well before he even started down his still-current road.

Does that mean this comic is “meta”? Yeah, I suppose that it does, but if you hold that against it, then that’s your loss. This represents both the apex and synthesis of everything Frankenstein’s been building up to, rendered in impeccably dulled-down and limited colors to reflect the world it takes place in, that being our own — as it really is. With all pretense, artifice, and bullshit stripped away. With the “man behind the curtain” showing in terms of both process and practice — note the exact reproductions of the boards Cassie drew and wrote this on, the cut-and-paste typography via which his “tone poem” narratives are presented. In stage magic and conspiracy theory this is referred to as the “revelation of the method.” Here we can just call it the way things are.

If I’d known the contents of this book ahead of time, I might have suggested Cassie call it The Secret Origin Of Tad Martin or somesuch, but in truth there are no secrets here, the interpretive, wordless, downward spiral of Tad #7 having put paid to that. Now, at the other side of dark phantasmagoria, all is laid bare: You go through years of torment, of humiliation, of questioning both identity and self (not the same thing), only to find that the promise of liberation, or even of self-negation (chemically induced or otherwise), was always a lie — we’re all cogs in a machine and the machine doesn’t care, Never will. Wasn’t built to. You can care about yourself if you wish — it may not even be the worst idea — but you’re still gonna end up in a pine box, and all those things that made you who you are gone in an instant, a universe of endless possibility reduced to the one from which it could never escape.

There’s a fair reading of this book that could conclude it’s a memoir of the artist’s coming to terms with his blackness in the face of the edifice that is white supremacy, and it’s not one I’m prepared to say isn’t there, but I think it’s both too broad and too narrow at the same time: This is a book about working-class blackness in a specific sense, yet it’s also about the plight of the working class generally. In which order and proportion I leave to you, but any way you slice it, from its noir stylings to it gorgeously rough-hewn assemblage and presentation (don’t let the slick cover fool you, this book is intensely lived-in) to its deliberately uneven rhyme and meter to its aura of perpetual and unending nightfall, this is singular stuff. So-called auteur comics at their most — I dunno, auteur-ish?

I asked a question in the title of this review and I’m now prepared to answer it — what happens after the darkness swallows you whole, as happened to Tad in #7? It pukes you back out at the exact same place you were before. The place you never left. The place you were always headed to. The scary part isn’t falling into the abyss — the scary part is realizing that it was inside you all along. And that it still is.

Tags: Casanova Frankenstein, Columns, Comic Books, Comics, Fantagraphics Books

No Comments