Throughout his career, Christopher Nolan has been fascinated with paradoxes His oeuvre is a series of men trapped in puzzles, driven by resolving contradictions within self-forged crucibles: a follower whose search for the truth only uncovers deceit, an amnesiac tortured by memory, a cop resorting to crime in the name of justice, a caped crusader whose obsession with justice is matched only by his desire to remove his cowl, illusionists blinded by their own obsession with theatricality, a team seeking truth in dreams, a father sending himself messages from the future, a country wresting triumph from the jaws of a colossal military failure, legions of soldiers moving forward and backward in time simultaneously. It’s no wonder, then, that Nolan would inevitably be drawn to J. Robert Oppenheimer, one of history’s great paradoxes. A polymath of extraordinary brilliance, he probed the secrets of the universe, only to usher in its possible destruction with the ultimate paradox: an unfathomable weapon meant to preserve peace. His life is undoubtedly one of the most momentous and consequential in all of humanity, and history is still reckoning with it. Is Oppenheimer a prophet heralding prosperity or doom? A martyr or a heretic?

OPPENHEIMER suggests he’s all of these at once, of course, because that’s what Prometheus was: a heretical firestarter who gifted mankind with the ability to sustain and destroy itself, a transgression that earned him eternal, recurring punishment from the gods. And while Oppenheimer’s liver presumably remained intact until his death in 1967, the eagles of history pecked away at the flesh of his legacy all the same, further complicating this riddle of American mythology. To solve it, Nolan sifts through the irradiated ashes of time in OPPENHEIMER, a three-hour cinematic reckoning that uncovers this enigma only to bring it into hazy focus as it untangles yet another paradox: here is the extraordinary life of a man reduced to the stuff of banal, petty politics during a pair of bureaucratic hearings seeking to determine just who J. Robert Oppenheimer was, a truth that remains elusive until Nolan’s camera captures it with a few brief, intimate moments that burnish the Modern Prometheus legend that open the film. Nolan has also often been fond of circular, looping narratives, so it’s not surprising that OPPENHEIMER opens and closes on a pair of its subject’s forlorn gazes, one from his days as an aspiring student, the other captured years after The Bomb, a closed loop that implies Oppenheimer was preternaturally destined for regret. The film marches in lockstep to this beat: it’s often thrilling, sometimes tedious, but always in motion, its wheels grinding with fatalistic doom.

It’s not as harmonious as Nolan’s previous loops, though that’s arguably by design when you consider the labyrinthine web he’s navigating. Technically, the film is framed by those two hearings: one a 1954 grilling to determine Opphenheimer’s (Cillian Murphy) possible Soviet sympathies as it relates to renewing his national security clearance, the other the 1959 Senate confirmation hearing for Lewis Strauss (Robert Downey Jr.), a government official who developed a professional rivalry with Oppenheimer while both men were members of the Atomic Energy Commission following World War II. Over time, a causal connection between these two hearings emerges, but only after both do their part to illuminate various chapters of Oppenheimer’s life: his days as a homesick student at Cambridge (where he’s explicitly drawn to the paradoxical nature of quantum physics, natch), his pivotal relationships with Jean Tatlock (Florence Pugh) and future wife Katherine Puening (Emily Blunt), his stint as a professor at Berkeley, and his most high-profile and infamous role in developing the atomic bomb at Los Alamos.

With the sharp instincts of editor Jennifer Lane, Nolan paints one of his signature non-linear portraits, though OPPENHEIMER is best compared to a puzzle full of jagged edges that’s being completed in a frenzy. Despite those hearings acting as anchors, the film darts in and around various points in time, creating a Tralfamadorian sense of displacement and dislocation: all of these moments exist as tableaus of a cosmic tapestry, which is how time often seems to work in Nolan’s films, whose paradoxes often can’t escape the gravity of destiny. As such, the confluence of events leading to Oppenheimer’s creation and testing of the bomb are treated like furiously scribbled parts of an equation, a matter of due course that underpin Nolan’s fascination with exploring their fallout. OPPENHEIMER isn’t exclusively preoccupied with understanding how a weapon of such mass destruction could be created because Nolan seems to be far more interested in how such a monumental event could be itself weaponized. The creation of the bomb haunted the rest of Oppenheimer’s days in more ways than one: there was the profound, existential angst, yes, but it also set off a chain of political ramifications that dogged his reputation until his death and beyond.

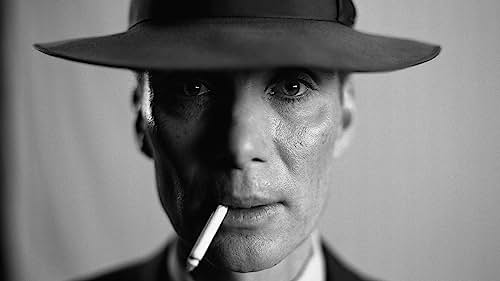

Oppenheimer remains enigmatic even here, in this three-hour adaptation of Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin’s 700-page biography AMERICAN PROMETHEUS. Even though we’re privy to some of his most intimate moments, the film remains at a certain, detached remove from its subject. It would seem that Nolan doesn’t think we can really account for genius; instead, we can only bear witness to it, so Oppenheimer is defined in the same manner as previous Nolan protagonists: by his sense of purpose and the machinery of that purpose. This is not to say that Murphy doesn’t find the human dimension in Oppenheimer: it’s there, mostly in those private moments, and he particularly captures the charisma that was no doubt instrumental in making him an effective leader. But mostly, Oppenheimer is a man who always looks like he’s seen a ghost both before and after the infamous Trinity test. Murphy’s sullen face, captured throughout the film in close-up, becomes the enduring image of OPPENHEIMER, a twin pillar of yet another paradox: for all of his obvious guilt and angst, Oppenheimer was also an extraordinarily confident man who remained steadfast in his belief in atomic weaponry until it was unleashed upon the world.

OPPENHEIMER is fascinating in part because it’s Nolan exploring what happens when a man’s great purpose blows up in his face, both literally and figuratively, and Murphy wonderfully navigates this emotional journey that posits Oppenheimer as a tragic figure of mythology, a man who was useful so long as the machinery deemed him so before it spit him out, leaving him with profound regret that manifests with the film’s stunning climactic, apocalyptic image. Dramatizing Oppenheimer’s life as a Promethean tragedy naturally extends a measure of sympathy to a man responsible for one of history’s great atrocities, but that seems to be exactly what Nolan is most preoccupied with, this great paradox that something so unfathomably destructive could be borne out of noble, misguided intentions. The film doesn’t stray from the historical insistence that The Manhattan Project was a tragic necessity in light of Nazi Germany’s attempt to create its own atomic weapon, and while this race provides filmic suspense, it’s also another crucible of machinery that leaves its cogs without a purpose after the war. Nolan particularly sees that fallout as being tragic, the way that shared sense of noble purpose became grist for the political mill within a decade, when its larger-than-life figures were dragged away from a great American Western frontier and cloistered into Senate chambers and dingy rooms, juxtaposing the sublime with the banal.

In doing so, Nolan also revels in watching that machinery hum. Like DUNKIRK before it, OPPENHEIMER is a testament to the fabled memory of the Greatest Generation, who, as legend has it, came together to thwart the greatest evil that ever plagued the planet. Nolan is reprinting that legend to an extent here, mostly with the cavalcade of monumental figures who fill out the supporting cast. Its roster reads like THE AVENGERS for physics nerds, boasting appearances from Niels Bohr (Kenneth Branagh), Ernest Lawrence (Josh Hartnett), Edward Teller (Benny Safdie) David Lawrence Hill (Rami Malek), Isidor Isaac Rabi (David Krumholtz), Werner Heisenberg (Matthias Schweighöfer), and even Albert Einstein (Tom Conti), whose cryptic conversation with Oppenheimer ultimately serves as the film’s Rosetta Stone. Matt Damon is Leslie Groves, the military officer who tabbed Oppenheimer to lead The Manhattan Project, and he brings his signature, understated dignity to the role, giving an otherwise detached film some emotional warmth. Krumholtz is instrumental in this respect, too: in an enormous cast filled with stars and beloved character actors, he nearly walks off with the movie as he emerges as its conscience.

Likewise, Florence Pugh is tremendous in her brief appearance as Tatlock, Oppenheimer’s doomed lover whose communist party membership casts a cloud of suspicion. Emily Blunt is Katherine Puening, the other woman in Oppeheimer’s life, a role that feels a little thankless at first when she’s depicted as a woman struggling with domesticity, unable to bear the burdens of motherhood as her husband’s work keeps him away from home. However, she eventually has enough backbone for herself and her husband because her communist sympathies also put her into the crosshairs, forcing her to endure her own grilling at the hands of a frightening cadre of bureaucrats led by Jason Clarke’s Roger Robb. Her fiery defiance clashes with her husband’s deferent approach in the same room, a contrast that tips Nolan’s hand in depicting Oppenheimer as an unfairly maligned martyr.

Then there’s Downey doing career-best work as Strauss, ostensibly the film’s villain whose jealousy of Oppenheimer causes the post-war rift to erupt in the first place. Only Downey doesn’t really play him that way — Strauss sees himself as the hero of his own story, a man who considered himself more virtuous and patriotic than his rival, and Downey nails that absolute conviction, particularly the way it curdles into smug self-satisfaction. His rapport with a senate aide (Alden Ehrenreich, who holds his own and then some) is dynamite political backroom theater, full of snappy dialogue and biting humor that mounts as everyone begins to realize the tide is turning against Strauss, echoing the gamesmanship and theatrics of THE PRESTIGE.

It’s among the most remarkable triumphs of OPPENHEIMER, this preternatural ability to turn such mundane proceedings into an enthralling thriller delivered almost primarily via close-up. Nolan’s gift for propulsion has never been more evident as it is here, as the film barrels back and forth all at once, filtering through anecdote and memory, with Lame’s laconic cross-cutting and Ludwig Göransson’s relentless score guiding a perpetual motion machine that slows but never stops until the end credits. There are times when the approach becomes frustrating, simply because it feels like a sensory overload, with names and faces coming and going, all of them leaving some sort of impression (look no further than Casey Affleck’s lone, bone-chilling appearance) even if their importance doesn’t immediately register.

However, like Nolan’s other puzzles, OPPENHEIMER resolves itself, mostly in its sparse lulls and quiet moments: a moody, postcoital conversation between Oppenheimer and Tatlock, the enigmatic exchange with Einstein, a striking opening shot that finds Oppenheimer staring at the ripples in a puddle, foreshadowing the film’s preoccupation with chain reactions. Even the Trinity Test is pitched at a hushed tenor that captures both the unbearable suspense of the moment and the sobering realization of its implication. The latter manifests in the film’s most unnerving sequence that finds Oppenheimer tasked with delivering a victory speech despite being haunted by images of a nuclear holocaust. Throughout the film, Oppenheimer is haunted by a thunderous cacophony that’s ultimately revealed to be the sound of rattling bleachers and stopping feet as he greets an adoring crowd, his ultimate moment of triumph soured into a bitter recollection, perhaps the film’s most potent paradox. It’s nothing short of astonishing, and it crystalizes Nolan’s depiction of Oppenheimer as a man haunted by his own creation, a Frankenstein figure descended from that modern Prometheus.

It might even be fair to call Nolan’s Oppenheimer a Modernist Prometheus spawned from the morass of the Lost Generation, whose fatalistic worldview heralded atomic era anxieties in both its literature (Oppenheimer notably reads Eliot’s “The Waste Land” at one point) and its psychology (he and Jean debate the merits of Jung). This might be OPPENHEIMER’s most interesting historical reckoning: the way that “The War to End All Wars” was simply the first spark in a 20th-century chain reaction that only led to more horrific warfare and even more unfathomable weaponry. History has made Oppenheimer an avatar for this never-ending sequence of escalation, of men creating bombs but already imagining bigger ones, but Nolan envisions him more as a golem shaped and molded from a clay that had been fermenting for decades. As much as OPPENHEIMER is about properly labeling the heroes and villains in all of this machinery, it’s also about how this machinery never stops — it will always be greased by animosity and blood as its rotating cast of boogeymen (Communism is just as powerful of a specter as Nazi Germany here) demands heroes and martyrs, sometimes all at once. OPPENHEIMER is American mythology writ large, the tale of a man who lived long enough to become a villain but was ultimately lauded as a hero just before his death.

But even that adulation comes with a sobering disclaimer: the ceremony is more for the machinery itself, not for the hero, who is left only to carry the burden. Like many great figures in history — not to mention several Nolan characters — Oppenheimer is whatever the present moment requires him to be, a useful cog in the machine that has no use for his foibles, guilt, and regret. Nolan insists those things should matter, though; otherwise, we only have the cold, calculating machinery itself when what we crave is mythology to help us solve history’s paradoxes.

Tags: Adaptations, Alden Ehrenreich, Alex Wolff, Benny Safdie, Casey Affleck, Charles Roven, christopher nolan, Cillian Murphy, Dane DeHaan, David Dastmalchian, David Krumholtz, Devon Bostick, Dylan Arnold, emily blunt, Emma Thomas, Florence Pugh, gary oldman, Gustaf Skarsgård, Harry Groener, History, Hoyte van Hoytema, Jack Quaid, James D'Arcy, James Remar, James Urbaniak, Jason Clarke, Jefferson Hall, Jennifer Lame, Josh Hartnett, Josh Peck, Kai Bird, Kenneth Branagh, Ludwig Göransson, Macon Blair, Martin J. Sherwin, Matt Damon, Matthew Modine, Michael Angarano, Olivia Thirlby, Rami Malek, Robert Downey Jr., Science, Scott Grimes, The 1940s, Tom Conti, Tony Goldwyn, Universal Pictures, World War II

No Comments