Okay, here’s the deal: I had this whole thing done — and probably done better — and I scrapped it. This now-meager memorial to the inimitable, irreplaceable Steve Ditko — artist, creator, visionary, iconoclast — initially had a soaring, elegiac title, was loaded with florid and heartfelt prose, and went into his work in excruciating, exacting detail.

It was a good piece. I liked it a lot. It took three-plus hours to whip it into shape. And then I shit-canned the whole thing and started over from scratch because I realized that’s not what Ditko would have wanted.

He was all about letting his work speak for itself, you see — that’s why he famously never gave interviews or appeared at conventions after 1968. That’s why he never wanted his photo taken. That’s why he headed for the exits at one publisher after another when he felt that his artistic vision was being unduly impinged upon. He poured his all into every page he ever drew, every line he ever wrote, and he wanted his efforts to be appreciated and analyzed for what they were, what he put into them, without distraction or obfuscation. This earned him a reputation for being uncompromising, it’s true — but I suspect he was probably quite pleased with that, as well he should have been.

And yet, so many of the other urban legends swirling around this singular genius are, to put it mildly, probably quite exaggerated: far from being a Greta Garbo-esque recluse, Ditko remained listed in the New York City phone book right up until the end of his life, at age 90, on June 29th of this year. He was known to welcome visitors, announced or otherwise, into his studio and engage in lively, friendly conversation with them. He communicated directly with his fans not only by means of his comics work, but through a decades-long series of thoughtful, precise essays laying out his views on any number of subjects, both comics-related and not. He was a well-known fixture on the streets, and in the businesses of, his neighborhood. Why, then, does this image of him as the urban equivalent of a lonely, isolated hermit persist? Well, I have a theory on that —

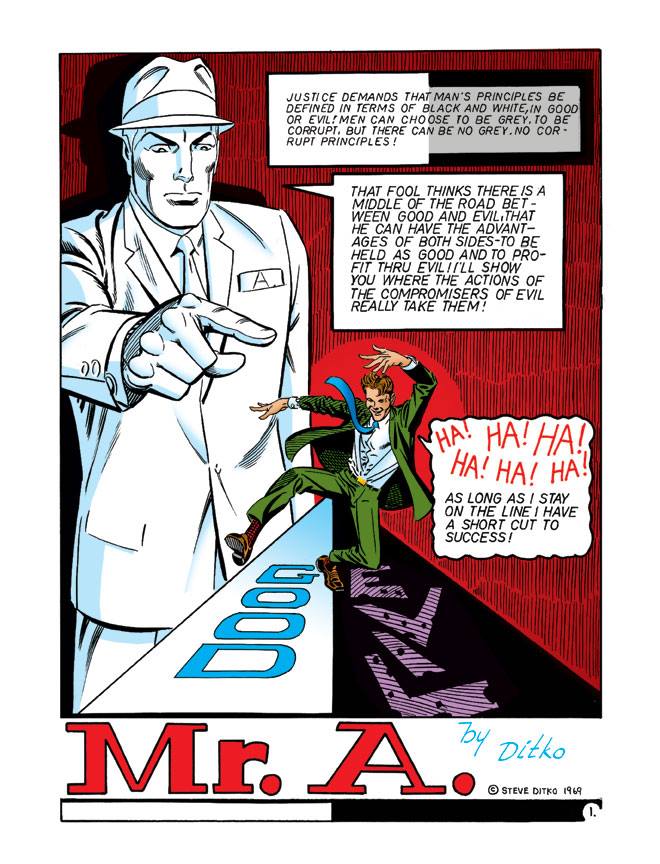

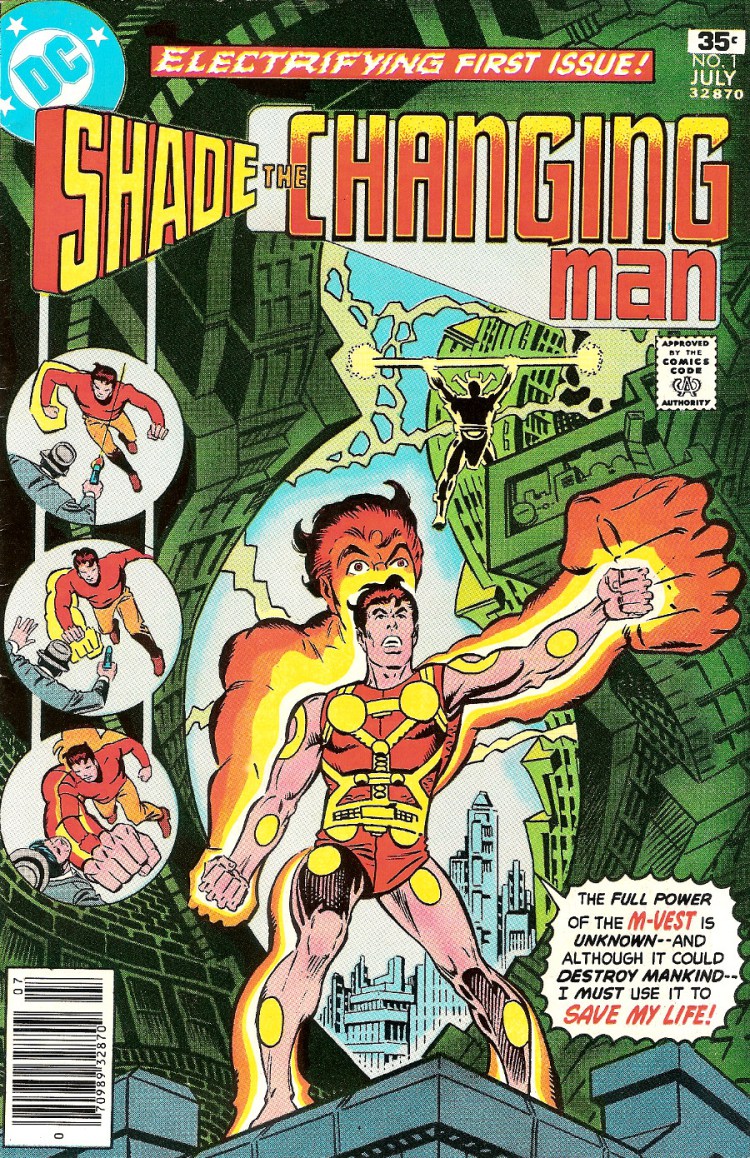

In short, I think it’s because he walked away — and he did so more than once. This man who created Captain Atom, Spider-Man, Dr. Strange, The Question, The Creeper, Mr. A, Shade The Changing Man, Electro, Mysterio, The Green Goblin, Hawk and Dove — this man who eschewed the Kirby-esque Marvel “house style” in favor of lanky, gangly figures quietly seething on the inside against an unconcerned, shadow-darkened world — he did something so many among his legion of fans could never understand. He put principle ahead of profit, integrity ahead of popularity, purity of vision ahead of commercial concerns. He made it to the mountaintop — overcoming a devastating childhood illness, making it through a stint in the army, moving from small-town Pennsylvania to the Big Apple in pursuit of his dream to “make it” as an illustrator — and decided he’d rather do things his way than continue to dilute his ideas and intentions to suit a mass readership.

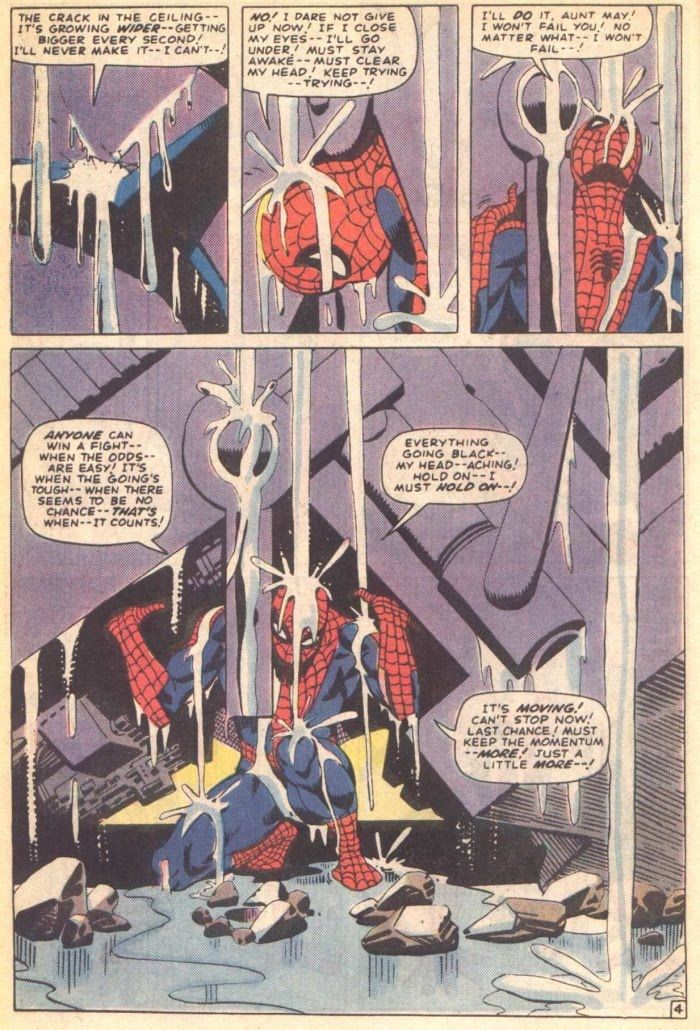

Consider: within months of creating the legendary “lifting sequence” in The Amazing Spider-Man #33 — arguably the most powerful and effective scene ever delineated in a mainstream super-hero comic book — he decided things weren’t working out to his satisfaction at Marvel, the company whose brand he helped build, and he went back to Charlton, the lower-rung company where he had cut his artists teeth in the 1950s, where he suddenly found himself afforded the opportunity to create idiosyncratic heroes more in line with his then-fully-developed Objectivist political philosophy, gradually coming closer to realizing the possibilities that came with unifying medium and message. Did it pay less? Sure. Was he happier with what he was doing? You bet.

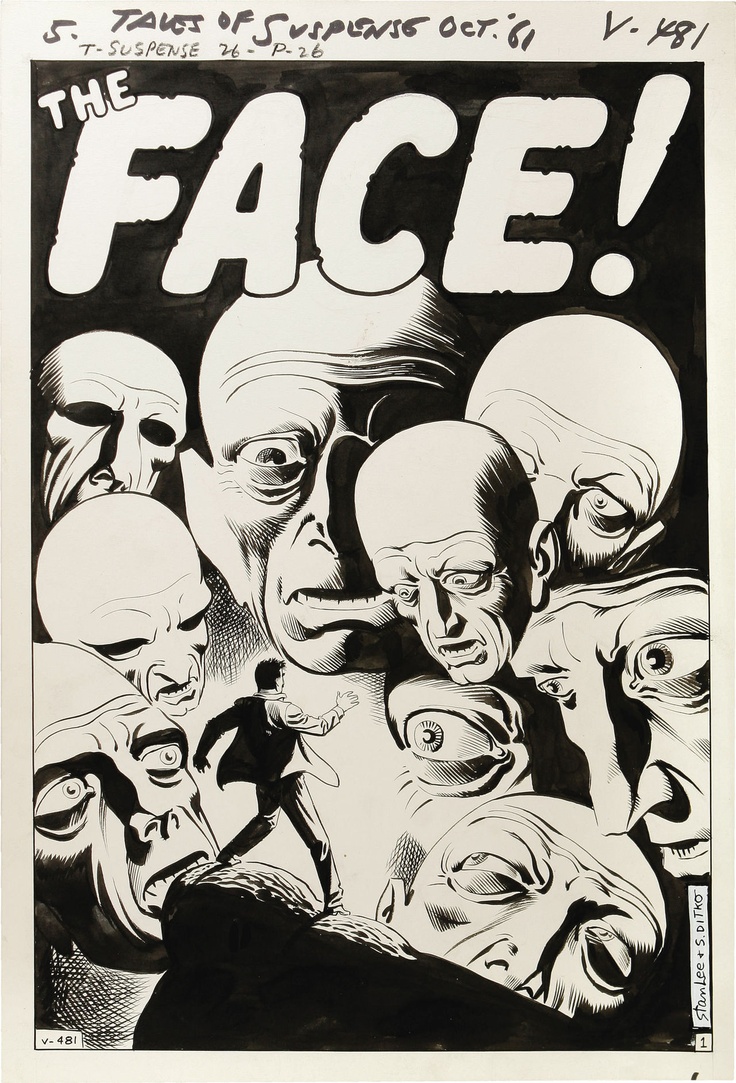

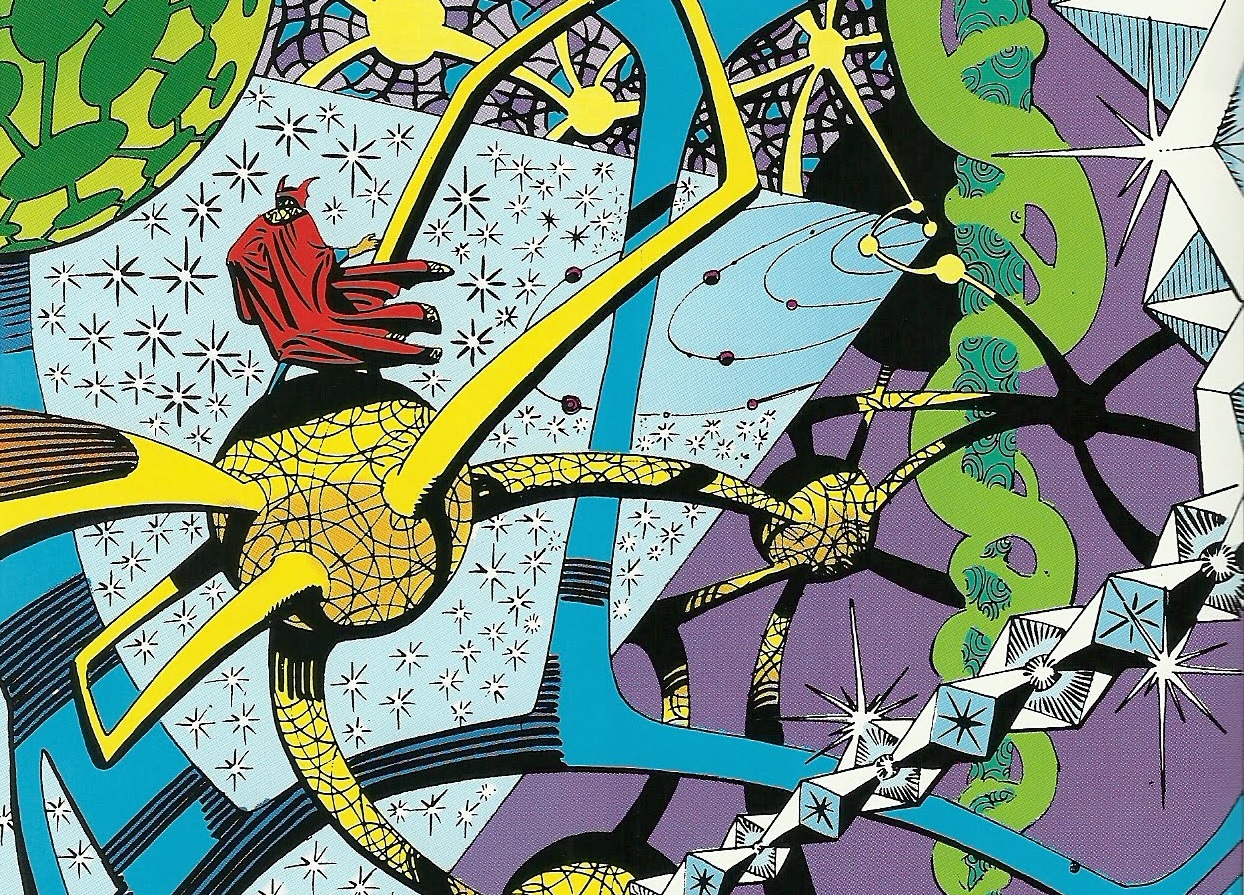

Still, for all his vaunted consistency, there were numerous — and frankly glorious — contradictions in Ditko’s body of work. A sober-minded rationalist and atheist, he nonetheless delineated the exploits of Dr. Strange with a special zest and zeal for the mystical and psychedelic, turning in page after page that looked like they could only have been conceived of on particularly intense acid trips. For all his stiff-upper-lip moralizing, he shared studio space, and created numerous erotic illustrations both for and with, noted fetish artist Eric Stanton. In spite of his fairly open disdain for decadence and excess, even his most steadfast and unyielding character, Mr. A, often found himself wandering through metaphorical mindscapes positively churning with imagery unleashed from the deepest and darkest corners of the human collective subconscious. Somehow, Ditko made it all work.

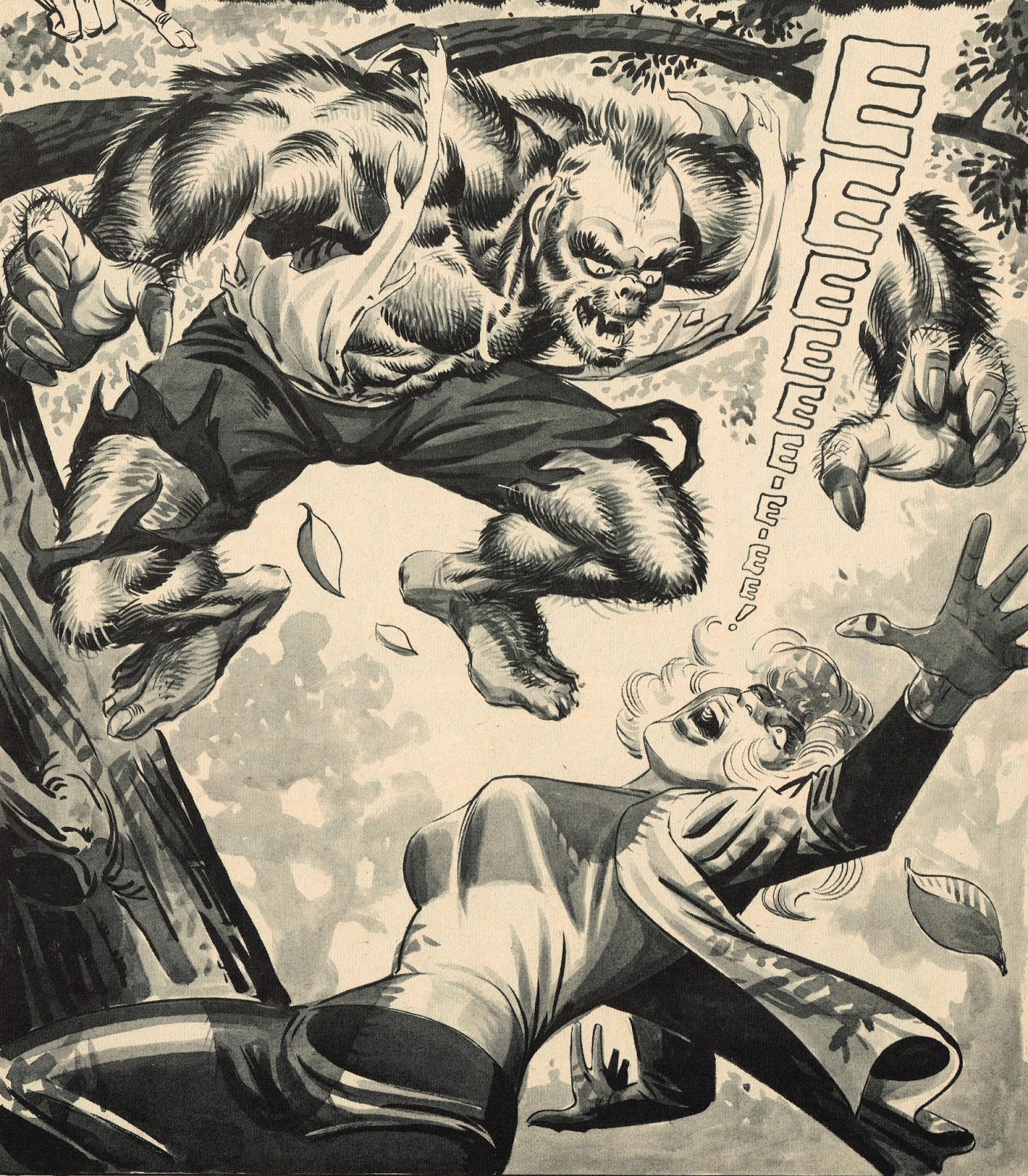

Perhaps most interesting of all his contradictions, though, was the fact that, despite having a clearly hierarchical worldview, he was willing to work for pretty much anyone under the right conditions. Concurrent with his late-’60s return engagement with Charlton, he was producing his amazing ink-washed pages for Jim Warren’s black-and-white horror mags Creepy and Eerie. Within a year or two of that, he was producing his first Mr. A strips for Wally Wood’s groundbreaking “pro-‘zine” witzend, while also taking on regular monthly assignments for DC. He went back to Marvel. Back to DC. Back to Marvel again. He dabbled with any number of publishers during the ’80 indy boom — Eclipse, Dark Horse, Fantagraphics. He certainly didn’t discriminate. Props to him for that.

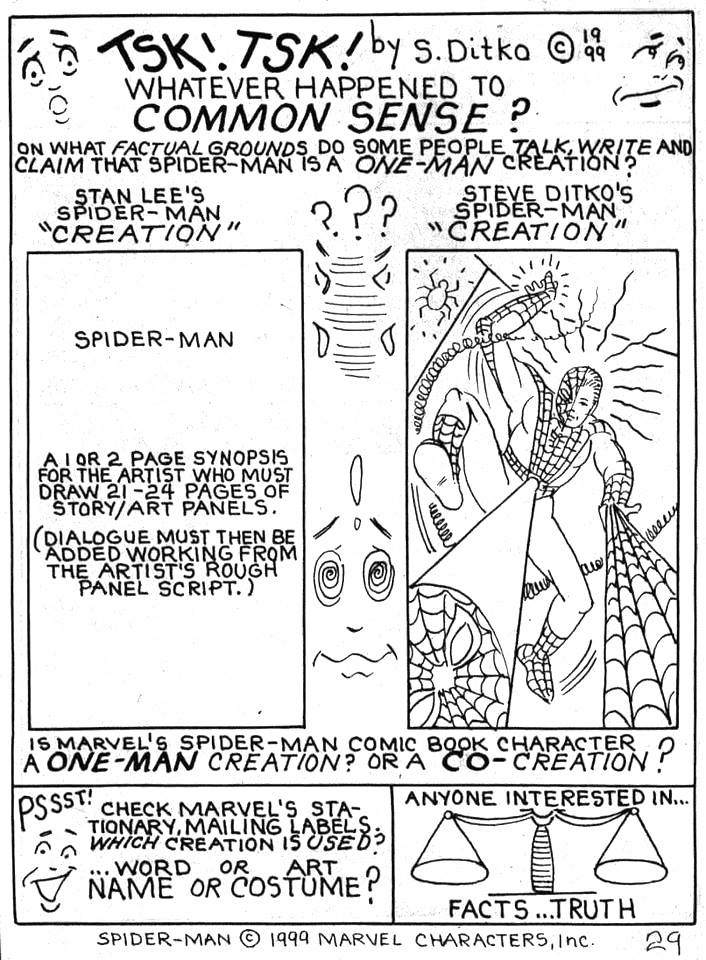

Sooner or later, though — something would happen. An editor would get too heavy-handed. A production flaw would rub him the wrong way. A plotline developed by a writer he was assigned to work with would run contrary to his Randian sensibilities. And so it’s probably no surprise that this lifelong trailblazer and innovator would find his final, and longest-lasting, publishing home at the company he started himself, along with friend and collaborator Robin Snyder. For the past 30 years, Snyder-Ditko publications has been producing a steady stream of both reprinted and all-new Ditko material, and along the way became one of the fist comics publishers to successfully finance their efforts via crowdfunding — a positively ubiquitous facet of today’s small-press scene that they figured out how to utilize well before most.

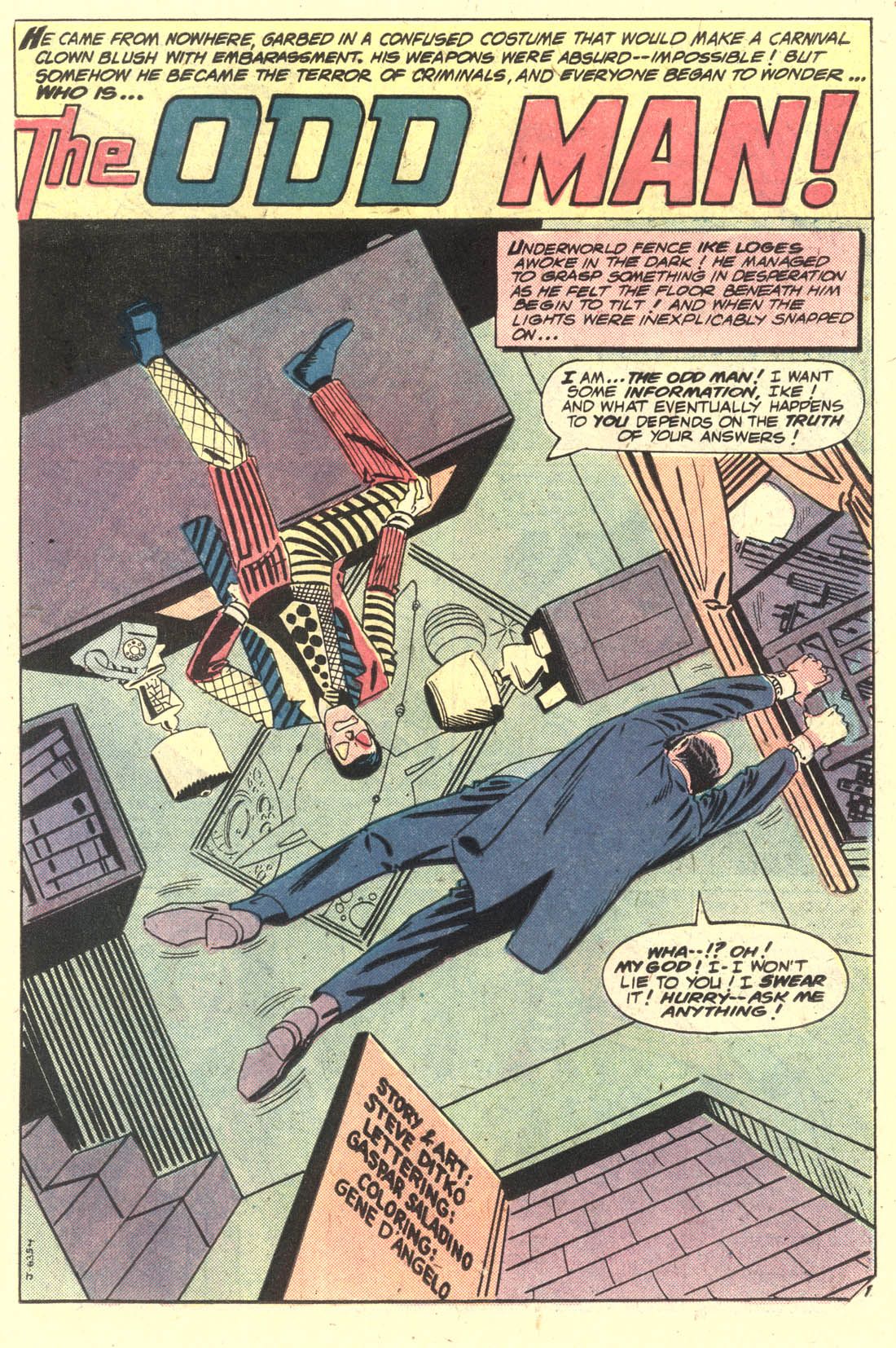

And at the end of the day, I think it’s that constant groundbreaking innovation — that unwillingness to compromise paired with an eagerness to experiment — that I’ll miss most about Steve Ditko. More than the crazy-fun characters — The Creeper had no real powers to speak of apart from an ability to jump around on rooftops and laugh maniacally, The Odd Man didn’t do anything except look and dress weird — and the bizarre names like Rac Shade and Mellu Loran; more than the impossibilities of form and function that emerged fully-formed from his mind and pencil; more than the moral absolutism expressed as clinical, matter-of-fact logic; more than the colorful floating polka dots and explosively vibrant extra-dimensional planes; more than the desperate faces of men moments away from complete nervous breakdown; more than the slender, coolly glamorous women with long legs and high cheekbones. More than — more than —

Hmmm — come to think of it, maybe I’m just going to miss everything about Steve Ditko in equal measure, because every aspect of all that he did was just so damn incredible. I’m fairly sure I will. Okay, I’m positive. But you know what? Maybe I don’t need to.

After all, Ditko — no believer in heaven, hell, or an afterlife of any sort himself — has achieved genuine immortality by the one and only means that he would ever consider appropriate: his work. It’s what he cared about most. What he devoted his life to. Indeed, what he lived for — and it’s never going away, even if its creator, sadly, has.

Tags: Charlton Comics, Comic Books, Comics, Dark Horse Comics, DC Comics, Eclipse Comics, Fantagraphics Books, Marvel Comics, New York City, Philosophy, Robin Snyder, Steve Ditko, Tributes, Warren Publishing

No Comments