There’s an unspoken mandate when it comes to sequels: every new entry must in some way push the franchise forward. For the most part, this is a good rule of thumb, since it makes each installment stand more firmly on its own as well as doesn’t cheat audiences returning for another round with an established universe.

Yet when a franchise’s original installment becomes a classic in part due to its intelligent, no-nonsense simplicity, plumbing new depths within the series can frustrate more than delight. That seems to have been the fate for the PREDATOR movies, a franchise which boasts four feature films (six, if you count the crossover entries with the ALIEN franchise AVP: ALIEN VS PREDATOR and AVPR: ALIENS VS PREDATOR—REQUIEM) as well as numerous comic books and video games. In the films alone, each subsequent entry has sought to explore and expand on the PREDATOR mythos, without the benefit of a central character or characters to continue to relate to. Each sequel and comic book added a new wrinkle to the mythos of the creatures (including a name for their species, “Yautja,” which didn’t appear until an “Aliens Vs. Predator” novel ironically entitled “Prey”), but such complexities began to take away from the “hunter vs. hunted” original concept. While the PREDATOR sequels are fascinating and, in some cases, bold reimaginings of what more could be done with an alien society of deadly hunters, the sense of pure, no-frills adrenaline-pumping fear and excitement that 1987’s PREDATOR elicited has diminished with each sequel.

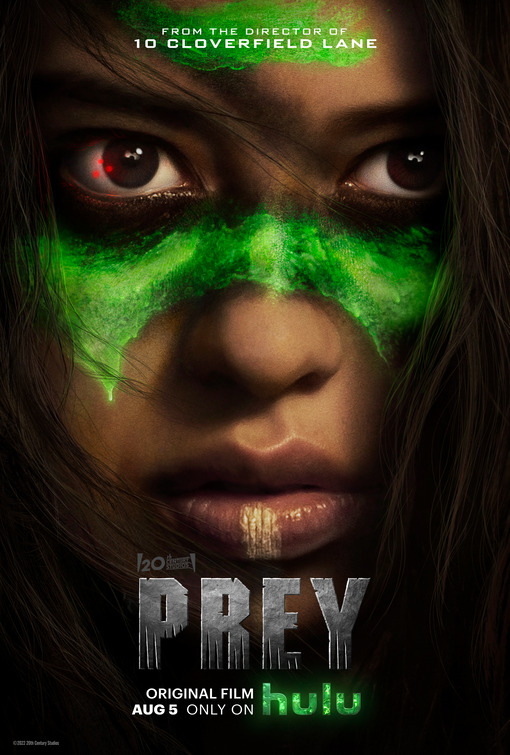

That’s not at all the case with the franchise’s latest installment, PREY. Being the second call-and-response-titled sequel to PREDATOR (following 2010’s pluralized PREDATORS), PREY is a prequel that manages to thread the needle of franchise filmmaking: it’s a back-to-basics installment that reinvigorates and revivifies what made the original film a classic, all while telling a story that feels utterly fresh. In fact, save some notable call-back moments that don’t draw too much attention to themselves, PREY is a largely stand-alone film.

Part of the reason PREY has license to pare the PREDATOR mythos back down to its roots is its setting in the year 1719. Set long before a group of mercenaries encountered a Yautja in the late 1980s, PREY follows a young Comanche, Naru (Amber Midthunder), as she attempts to prove to her tribe and especially her family that she is worthy of becoming a fully-fledged warrior. The patriarchal society of the Native Americans means her tribe expects her to fulfill a more traditional female role of healing the sick and wounded, while her family mollifies her ambition to join the hunt—Naru’s brother, Taabe (Dakota Beavers), is War Chief of the tribe, and respects his sister while warning her that the rite of passage she wishes to take involves not just hunting something, but being hunted by that prey at the same time.

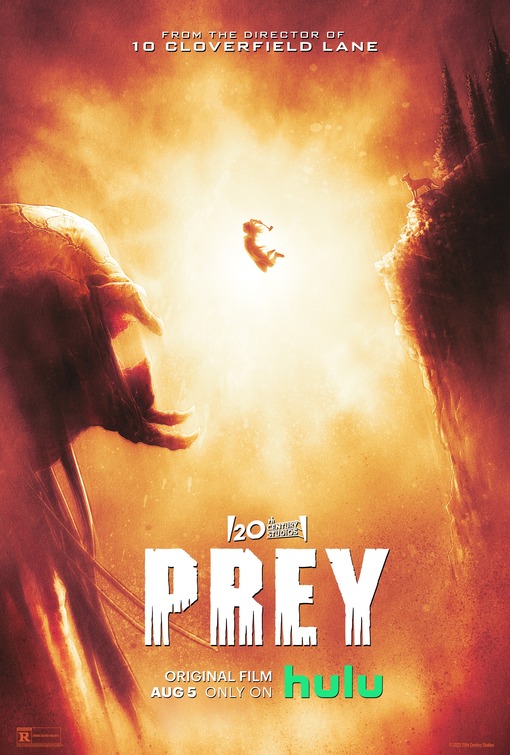

Of course, Naru gets more than she’d wished for when a Yautja craft drops off a lone Predator (Dane DiLiegro) in the Comanche Nation, a warrior who begins testing his might with the various deadly members of the animal kingdom in the area before moving on to nearby Comanche hunting parties. The film engages in a little girl-who-cried-wolf structure, with Naru attempting to convince her tribe that a threat bigger than a bear or lion exists out in the woods, to no avail until it’s too late. Forced by circumstance to confront the Predator on her own, Naru finds herself undergoing her rite of passage into warriorhood in a big way.

Where prior PREDATOR installments sought to further develop the culture, structure, and arsenal of the Yautja species, PREY brings things back to basics in most intelligent fashion. Most sequels to the 1987 original explore the primal darkness inside humanity, with PREDATORS in particular fixating on how a killing instinct is developed. PREY, on the other hand, takes another look at the Predator’s analogous relationship with the natural world. Naru and her Comanche tribe are not portrayed as savages or sadistic murderers—to them, killing is about both honor and survival, a natural relationship as opposed to a moral aberration. Sure enough, the presence of some French trappers near their land provides that tried-and-true counterpoint, since the White hunters all too happy to revel in their aggression and sadism. Yet this is only a (admittedly great) subplot in the movie, and is the one area that treads closest to where other PREDATOR movies have gone before.

PREY instead hews closer to a survivalist narrative, not taking a cue from war films so much as emulating movies like 2011’s THE GREY and 2015’s THE REVENANT. With the spirited but still green Naru having to face a superior foe in both technology and experience, her struggle is akin to Dutch (Arnold Schwarzenegger) having to face down a Yautja by himself at the close of the first PREDATOR, using only what can be found in the woods around her. Midthunder makes Naru credibly resourceful, her strength and resilience overcoming her vulnerability. There is, of course, a feminist subtext to the film and her character—while no one is openly misogynistic toward her (save the Frenchmen), the film depicts the way the Comanche society is rooted in restrictive gender norms and stereotypes that Naru must break through. Appropriately, though prior PREDATOR movies have featured female characters in major roles, PREY marks the first time the franchise has featured a sole female lead (again, not counting AvP, but that entry also acts as an ALIEN film, and that franchise is notable for consistently having a strong female lead).

In addition to Midthunder’s excellent performance, the solid work from the rest of the ensemble cast, and Patrick Aison’s smart, well-structured script, the film excels at its action, featuring some of the best action sequences in any PREDATOR movie. Director Dan Trachtenberg proves once again his incredible touch with eliciting tension and suspense that is then paid off with hard hitting action beats. As he did with 2016’s 10 CLOVERFIELD LANE and the BLACK MIRROR episode “Playtest” that same year, Trachtenberg brings a sense of clarity and impact to PREY’s action that seems to stem from modern-day video games. In conjunction with stunt coordinators Jeremy Marinas and Steven McMichael, Trachtenberg furthers his penchant for presenting action in a clean, sharp, and brutal style. There’s nothing balletic to be found here—the Predator’s attacks are shockingly swift, and Naru’s offense is all about outsmarting her foe, the mind games she has to undertake combined with preparation underlines the movie’s exploration of someone hunting while being hunted at the same time.

Ironically, it’s all of this well-crafted, back-to-basics excellence that proves the PREDATOR franchise is far from being on its last legs. While there are a few neat moments in the film that fans of the series will appreciate (such as references to classic lines of dialogue as well as, in one instance, a clever nod to PREDATOR 2) and this movie’s Predator carries some neat new gadgets and weapons that add to the Yautja lore, PREY isn’t just a good sequel, but a great movie, full stop. For that reason, it’s even more infuriating that 20th Century Studios and Disney are dumping it on the streaming service most people refer to as “oh yeah, that one”—if it had been granted a theatrical release, I believe it could’ve done solid business, continuing a summer movie season where films like TOP GUN: MAVERICK demonstrated that franchise films can and should be good movies first, IP torchbearers second. In any case, PREY proves that 10 CLOVERFIELD LANE was no fluke, Trachtenberg’s the real deal, Midthunder can carry a film, and the PREDATOR franchise isn’t so easy to kill. For solid sci-fi/horror/action entertainment this summer, you don’t have to hunt very far.

Tags: Action Film, Amber Midthunder, Claudia Castello, Dakota Beavers, Dan Trachtenberg, Dane DiLiegro, History, Jeff Cutter, Jeremy Marinas, Jim Thomas, John Davis, John Thomas, Julian Black Antelope, Michelle Thrush, Monsters, Patrick Aiso, Sarah Schachner, Sci-Fi, Steven McMichael, Stormee Kipp, The US

No Comments