Lina Wertmüller defied easy categorization. She was a provocateur in the purest sense: she did not seek out shock or discomfort for their own sakes — she was simply comfortable in a world where many would not be. Even describing her films in pithy blurbs does little to dull their sensibilities. The film for which she would gain the most international attention, SEVEN BEAUTIES, shows us a journey through fascism, with stops in brothels and concentration camps. And yet it was — and remains — funny! This was the film that garnered her an Academy Award nomination, something hard to conceive of today for such a challenging picture. Because of this, however, she is often represented in film history as a factoid — the First Woman To Be Nominated. But that does her a great disservice. She did not measure her accomplishments in prizes won, or the dubious honor of American industry nominations, and neither should we. “Prizes are like butterflies… that fly away,” she told The Hollywood Reporter.

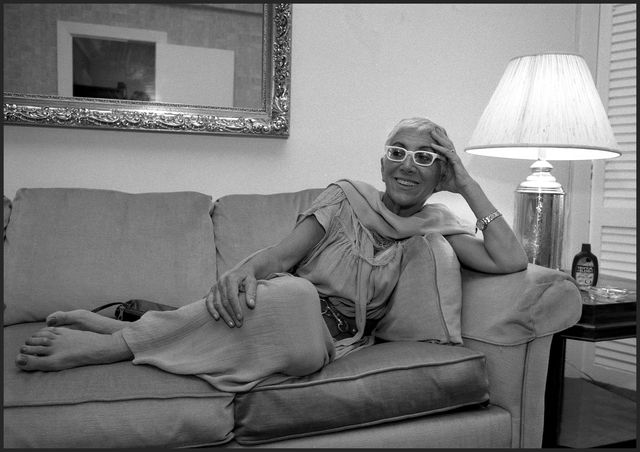

It is best to remember her this way, through her words. The documentary BEHIND THE WHITE GLASSES offers many chances at this, around the occasional stiff academic talking head. The director was eighty-eight at the time of filming and still active in the art world, directing theatrical productions and writing raucous songs (though her last feature film was released eleven years earlier, in 2004). The film’s opening includes one of those songs, though first we hear the sound of typing, and are shown shots of ornate lamps and framed pictures of the director with friends and family. Quickly, the more typical setting for a person of Wertmüller’s age and status gives way to her sensibilities. We hear what she is working on — a delightfully vulgar description of an orgy. “Ass and tits!,” she says, as the music track fades in and we cut to her in a recording studio, singing her writing as an “ode to Bacchus” for the microphone.

Wertmüller began adult education as an acting student, two years too young for the filmmakers’ school. She performed musical comedy initially, and then social-realist plays, saying that within her, “Two souls coexist, a magical comedy one and a socially-conscious one.” Her technical film career began when she applied to be the assistant director on Fellini’s 8 1/2 through a friend. She got the job, though she says, “I was a lousy assistant director, but they overlooked it because I was likeable.” She shot her first film, THE LIZARDS, in that same year of 1963, taking much of the crew from the Fellini picture with her upon completion. Fellini encouraged her to ignore technical advice and tell the story as if at a party, saying that no technical skill would be able to save her if she couldn’t tell a story well.

Men, and chauvinism specifically, interested Wertmüller artistically from the very beginning. Perhaps this was in some part due to her work on 8 1/2, a portrait of filmmaking as masculine neurosis. She talked about Mastroianni (the lead actor) and Fellini’s philosophy on the set, that they treated life as one big party. It’s easy to map this attitude onto characters like the boys in THE LIZARDS or the titular Mimi in THE SEDUCTION OF MIMI. This kind of philosophy takes on a darker turn in much of Wertmüller’s work, though she did also have a fondness for these men and their antics. She was just also aware of how much destruction it could lead to.

Make no mistake: Her style was all her own. Influenced primarily by the rich history of Italian Neo-Realism, Wertmüller knew also to listen to that other side of her soul as well — the comedic one. Neo-Realism was beginning to run its course in Italian cinema for more surreal and expressive works, and her films became stunning examples of this, all about the absurdity of life. They remind me most of when in a group of women, one might share an anecdote about a bit of sexism experienced in life, and we, the other women, will laugh in response. It’s a communal event to purge anxiety about the ways the world we live in mistreats us. It’s cathartic, in a laugh-or-you’ll-cry sort of way. The laugh isn’t a pure one — it’s frustrated, a knowing laugh about the ways of the world. Wertmüller made films that were those frustrated; knowing laughs, expressions of a deeply sexist society mired in recent fasicm. She knew, and expressed through her art, a fundamental truth: if you’re not laughing, you’re crying.

The white-bespectacled Italian auteur was ninety-three when she passed this December.

Tags: 2021, Italy, Lina Wertmüller, Tributes

No Comments