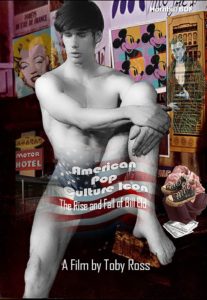

It’s safe to say that we’ve entered something of a Golden Age of streaming documentaries. Between HBO Max’s THE VOW, CLASS ACTION PARK, and THE WAY DOWN, Hulu’s FYRE FRAUD and WEWORK, and myriad other high-gloss, multi-part, deep-dive explorations of everything from true crime cases to lost chapters in pop culture history, there’s no shortage of slick programming for information junkies to gorge themselves to their heart’s content. Quietly issued as an independent release from Hornbill Films in 2020, Toby Ross’ BILL ELD: AMERICAN POP CULTURE ICON, may not have the polish and complexity of the latest streaming release, but it nonetheless emerges as something much more intimate, personal, and compelling than anything money could buy.

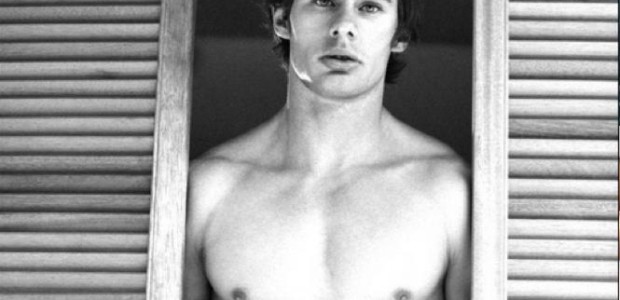

If you’re not familiar with the name Bill Eld, you’re not alone, and that’s quite the point of the documentary: for a generation of queer men coming of age in pre-Stonewall, pre-Harvey Milk America, Eld was a face as readily recognizable as Marilyn Monroe or Jayne Mansfield was to heterosexuals. A fixture of fitness and “physical culture” magazines, Eld’s good looks and bodybuilder physique made him an object of lust and fascination, a reputation he successfully parleyed into a career as an adult film star during the Golden Age of Porn. Yet for as much of a queer icon as Eld became, the life behind the body was a mystery. Virtually no biographical information about him was published during his lifetime, and he drifted around the country with such regularity that he hardly made any lasting connections. Indeed, as we learn in the opening minutes of the documentary, Eld—who died in his early forties under mysterious circumstances—isn’t interred in some family plot but rather an unmarked grave on Hart Island, the infamous New York Potter’s field used as mass-grave at the height of the AIDS crisis. Ross- who knew Eld during two key periods in both mens’ lives- seeks to explore the mystery behind the man while also solidifying his place in queer history and paying tribute to a lost friend.

Viewers used to the million-dollar aesthetics of prestige documentaries will find themselves immediately startled by ELD’s opening moments. A passion project produced at the height of the COVID-19 crisis, the bulk of the film consists of something of a long-form monologue on Ross’ part. Looking directly into the camera from the confines of his home, Ross—himself a prominent 70s queer filmmaker whose films bridged the gap between porn, exploitation, and art cinema— extemporizes on Eld’s life, sharing the few bits of information we know about him, Ross’ memories of their time together, his own theories on Eld’s psychology and motivations, and his place in queer history. While the impact is jarring at first, something remarkable quickly happens: what the documentary lacks in money or slick production values it more than makes up for in Ross’ natural gifts as a storyteller. Alternatively wry, insightful, witty, sarcastic, playful, and sincere, you quickly forget that you’re watching a movie and come to feel that you’re having a video chat or cup of coffee with a beloved grandfather, as Ross’ stories weave in and out of one another and he paints a panorama not only of Eld’s life but gay America in the 1970s. Against expectations, the DIY aesthetic becomes one of the film’s biggest strengths, and more fully immerses the viewer in Eld’s world. Ross establishes this unconventional tone early on with a pair of sequences that help set the stage for what’s to follow:

In the first, he pauses the documentary for something approximating a music video, which takes the form of a montage of images of Eld through his career. Spanning a variety of years, tableaux, and milieus, the montage serves to establish Eld’s prolificacy, pays tribute to his physical beauty (Eld could easily have held his own with the bodybuilders of the 1970s), and, through the use of David McWilliams’ haunting folk rock song The Days of Pearly Spencer, underscores the air of tragedy that followed Eld through so much of his life. It’s an evocative, provocative sequence that—while unconventional—feels more raw and personal than had Ross relied on talking heads as a source of information.

In the second sequence—a tonal whiplash from the first—Ross playfully interrupts his own movie with a “breaking news” segment in which he reveals he managed to track down some of Eld’s last living relatives, one of whom—his nephew—has agreed to be interviewed. It’s a fun, funny narrative conceit that underscores this isn’t so much a documentary as a tribute, love letter, and personal reminisce on Ross’ part.

Indeed, the parts that are the most engaging about ELD are those in which Ross himself takes center stage in the narrative: having briefly worked with Eld in California when they both lived there in the 1970s, the pair fell out of touch, until a chance encounter led to their reconnecting in 1980s New York, where Ross was working an office job and Eld was a virtually homeless drug addict living in a grindhouse basement. What emerged was a sort of GODS AND MONSTERS by way of TAXI DRIVER chapter in the pairs’ lives as Ross struggled to help his old acquaintance get back on his feet and Eld slipped deeper into his vices. As Ross explains in a particularly touching monologue, he actually filmed a brief documentary Eld near the end of his life, an intimate, one-on-one conversation shot on video in a squalorous NYC abode that’s since been lost to time and which this film serves as a spiritual remake of. Breaking down on camera, Ross makes a posthumous apology for not being able to help him successfully beat his addictions, before shifting gears and eulogizing him in a touching tribute that syncretizes Eld with Icarus, another figure who reached spectacular heights only to suffer a final, crushing defeat.

There are other striking moments about ELD- one sequence finds Ross using a photo of Eld as the springboard for a complex psychoanalysis of the real man behind his meticulously crafted public persona, while a mid-film segue finds Ross exploring Eld’s role in the career of postwar homoerotic artist Harry Bush (a mini-documentary of Bush appears as an extra on the DVD.) Some other sequences may prove offputting to viewers—twice, the documentary comes to a halt to showcase two of Eld’s porn reels in their entirety, breaking the narrative momentum. These moments are few and far in between, though, and overall, the film emerges as a fitting tribute to and memorialization of a key figure in the evolution of queer American pop culture. For anyone interested in the world of 1970s and 80s queer cinema and life, ELD is destination viewing.

BILL ELD: AMERICAN POP CULTURE ICON can be purchased at Amazon

No Comments