If you’ve been even moderately plugged in to literary Twitter (wither, X), Bookstagram, or the writing blogosphere the past couple months, then you have undoubtedly caught a whiff of Alex Kazemi’s controversial debut novel new millennium boyz. Forthcoming from Permuted Press (a kind of quasi-indie imprint distributed by Simon and Schuster), the book has garnered all sorts of attention due to its “dangerous” content, its publishing team’s insistent promotion of said content, and the subsequent backlash to said promotion, all of which has made it pretty hard to avoid.

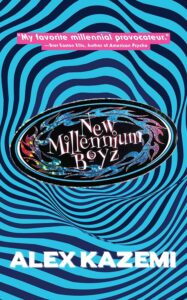

Armed with a gender-baiting dedication “To anyone who was ever born a boy”, an outrage-baiting epigraph from alpha Columbine killer Eric Harris, and a counterculture-baiting front cover blurb from none other than 80’s dirtbag impresario Bret Easton Ellis, the new millennium boyz team proceeded to flood the zone with ARCs (I heard a rumor they sent out as many as 400, further cementing their status as, to quote a writer friend of mine, “indie lit cosplay”), before subsequently pestering several writers who wrote negative reviews to take them down, reportedly making some reviewers very uncomfortable, and just generally badgering everyone else for real-time reactions to their antics. Considering that Kazemi had already been profiled in A-list publications like Vanity Fair and Interview (and decried the indignity of social media self-promotion from their lofty pages), it all felt a little suspicious, as though they were after something other than coverage or cred. It felt like they were crowdsourcing the very outrage they’d wrought – pissing people off just enough to be able to say they “got canceled” without actually getting canceled – retconning what worked, what didn’t, and what they could feed back into their edgelord marketing machine.

That was my initial impression anyway.

I don’t know how much these guys looked into me before asking me to read/review, but as someone who lived through the first post-Columbine school shooting (Heritage High School, one month later to the day, 6 wounded, no dead – I was a freshman – as long as we’re shamelessly self-promoting, I wrote some about it here) in Rockdale County, Georgia (yes, that Rockdale County – I was a sophomore when the Lost Children documentary – directly referenced in new millennium boyz – premiered on PBS. And no, I don’t have syphilis), and recently published his own debut novel, Troll (with actual indie publisher Whiskey Tit Books – I guarantee you 400 copies haven’t even been printed yet) about a 30-something internet troll devolving into media-saturated alienation and psychosis (complete with its own bait-y front cover blurb – “Fight Club for the Twitter generation” – check it out here) I am about as obvious a target audience member for new millennium boyz as a person could be. I am, quite frankly, the bullseye of their target audience. And knowing that about myself is… not a great feeling.

I’m not going to lie here. When I first saw that blurb splashed across that Now That’s What I Call Transgressive Literature! cover art, my immediate, gut-level reaction was abject jealousy. I would give the non-dominant half of any body part I have two of to be Bret Easton Ellis’s “favorite millennial provocateur,” and a lot of other writers I know would too. We might claim otherwise, but deep down, no one spends years of their lives writing 400-page novels about drugs, sex, death, and druggy sex-death, without a little voice in the back of their head whispering “man, how dope would it be if Bret Easton Ellis (or Dennis Cooper, or Chuck Palahniuk, or Ottessa Moshfegh, or take your degenerate pick) reads this someday?” For better or worse (probably worse), “transgressive literature” has become its own robustly defined and commodified subgenre. It has canonized icons, mainstream luminaries, and several tiers of alt-strivers. There is an online community. There are, I would posit, even rules, amidst all the “fuck the rules” posturing. Unspoken expectations of a certain courtesy – a certain good faith benefit of the doubt – rules that, to his legitimate credit, Alex Kazemi (and his team) have found some interesting methods of disrupting.

Fight Club is probably where it all really started going off the rails. Which is not to say that people hadn’t misinterpreted and/or taken the wrong lessons away from transgressive literature before it – that’s a problem as old as literature itself – but rather just that I’ve never met anyone who read Less Than Zero and promptly decided to devote their life to coke. It was siloed before Fight Club. Less mainstream. Less of, as the kids say, a thing. But come 1999, (and through no fault of his own), Chuck Palahniuk activated an entire generation of young men who read Fight Club (or, more likely, saw FIGHT CLUB) and came away viscerally thrilled, but thinking little more than “I should start a fight club!” That book accessed a primal, and deeply suppressed desire in a lot of guys my age to feel something real in an increasingly synthetic world – one hardwired to our basest desires, and growing more adept by the day at selling them back to us before we even knew they were what we wanted (or, more insidiously, before we knew what we wanted at all). Calling out “the corporations” and “the machine” wherever they reared their ugly heads grew into something of a teenage millennial pastime. Wary cynicism became an identity unto itself. And like clockwork, it too was promptly swallowed up, smartly packaged (mostly in black), and retailed for a tidy profit.

If there is one thing new millennium boyz does extraordinarily well, it’s establishing that capitalist fogbank of relentless consumer culture. The “boyz” in question – Brad, Lu, and Shane, three high school seniors circa 1999/2000 – speak with a hyper-specific brand awareness that reads like direct homage to Patrick Bateman, but instead of the power suits and soft rock of the yuppie 80’s, it’s Tommy Hilfiger and Marilyn Manson; Mickey D’s and Mountain Dew; Blockbuster and MTV and Girls Gone Wild. Riding the post-Satanic Panic poptification of occultism and devil worship right into the post-Cobain commodification of depression and “authenticity,” this extremely unpleasant trio of proto-trolls (indeed, with a few narrative tweaks, I could see any one of them growing up into the nameless protagonist of my book) have arrived simultaneously at the brink of adulthood, the turn of the millennium, and the final frontier of exactly what all could be bought, mass-produced, and sold. (Seriously, think about it. After “authenticity,” what’s really left?)

Having been born in 1983 (one year after the boyz) I remembered it all like it was yesterday. I’d guess the book averages between 10 and 20 pop culture references per page, from the horrifyingly ubiquitous (LIT, AMERICAN PIE, Total Request Live) to the hyper-specific (Heather Nova, SoBe, The Ethical Slut), and I rarely had to look anything up (Black Circle Boys was a new one though. Respect). I remembered how kids one day just suddenly started showing up to school in $50 t-shirts with nothing on them but the brand name (“label-strewn conformists” I called them. Yeah, I was that guy). I remembered how much I hated The Backstreet Boys and Britney Spears, not because I actually hated them mind you, but because I was supposed to hate them according to the pre-algorithmic channels through which all music was funneled to us. And I remembered how much I loved Rage Against the Machine and Tool by contrast, as though they were somehow outside those corporate systems, rather than just differently marketed parts of them (have you looked at prices for Rage or Tool shows lately? Lmfao). But most of all, I remembered how much we defined ourselves via those force-fed false dichotomies – between what we loved, and what we hated – and what that said about who we were and how we saw each other. The way we identified ourselves – created our “selves” – through our stuff.

All of this stylized referentiality is hard to read at first. The book is probably 80% dialogue, and as such, some part of your brain naturally resists it with thoughts of “no one has ever talked like this.” But after a while, there develops a kind of rhythm to it – the ratatat pinging of nostalgic brainwaves. The subconscious understanding that your own fond, youthful memories are being weaponized against you; greasing the wheels of empathy. It pulls you into the boyz’ media-saturated world in a way that more realistic teenage dialogue never could. Because of this, they can sometimes feel less like characters than archetypes, but their archetypicality (if that’s a word) is a direct product of the grossly misogynistic entertainment landscape they spend all their time absorbing and reflecting back at one another; living conduits driving their own cultural feedback loop.

It helps that they’re often talking into Lu’s Handycam which, from the vantage point of our 2020’s hindsight, feels almost like a portal to Hell every time it’s flipped open – a retronymic precursor to our present-day social media surveillance state panopticon – a nod to the beginning of the end. The boyz are constantly noting how life is and isn’t like various movies (Gregg Araki? Yay!; SHE’S ALL THAT? Nay!), and likewise constantly performing – for the camera, sure, but also, and probably moreso, for each other; forever endeavoring to bridge the gap between their banal, suburban lives and the gritty, porny, MTV Beach House fantasies they’ve bought into. Lu (the Manson-worshipping sociopath ringleader), spurs on Shane (the clinically depressed Billy Corganite), and Brad (the blink-182-loving little boy lost) to stranger and darker acts of depravity, both on and offscreen, and the toxic triangle that forms between them definitely hits some resonant notes regarding the competitive one-upmanship inherent in virtually all male friendship (especially at that age). Even when they do get real with one another (most affectingly in chapter 74, when Brad and Shane are away from sadistic puppet master Lu and briefly approach something close to poignancy after 200 pages of vitriol), it always comes back to bite them. They operate like a closed triptych of funhouse mirrors – bro, brah, and bruh – variations on a theme of adolescent male isolation, yet wholly incapable of trusting what they see in one another. Vulnerability is weakness. “Caring is so embarrassing.” Feelings are for girls.

And let’s talk about the girls for a minute, because that was easily my biggest gripe with new millennium boyz. Brad has sporadic conversations with a college-age female friend, and exchanges achingly cringey love letters with his homeschooled camp girlfriend (as the majority of my high school dating life was devoted to a long-distance college-age girlfriend, I felt these bits blushingly hard), but neither of these characters is provided much depth, and every other girl in between is little more than a nagging mother or vacuous stereotype. You could absolutely argue that we’re just seeing women the way the boyz would see them, and I’m hardly a subscriber to the pandering modern ethos that all viewpoints must be represented equally in all works of art (the multicultural college brochure approach to storytelling), but the star of new millennium boyz is pretty decidedly the time period it depicts, and the degree to which it flattens the female experience of that time period feels like a missed opportunity. Any time you find yourself arguing that the straight, white, male experience has been somehow marginalized – even if what you’re saying about that experience is 100% true – you’re betraying an inherent privilege. All this shit was bad for girls too. Exponentially so. Suggesting that any of it was somehow exclusive to boys, or worse for boys, is patently absurd.

And indeed, if Kazemi is truly sincere in his diagnosis of what troubles the straight, white, suburban, millennial male – and after reading chapter 82 of this book, as well as several interviews with him, I became convinced that he is – then he’s not exactly off base. But I definitely felt some discomfort upon learning that he was born in 1994, and that his depiction of this time period is the product of meticulous research, rather than lived experience. Poring over MTV archival footage and Delia’s catalogs and old message boards is all well and good in service of the rampant product placement atmosphere he set out to establish, but it makes me a little queasy knowing that this book might well become a touchstone for an era its author never experienced. I’m not trying to say anything as simplistic as “I was there, and it wasn’t like that,” but the nonstop hatefulness of it – the sexism, the racism, the homophobia, the violence – is garish, and concentrated in the extreme. I get that it’s satire, and I appreciate the effect, but it sometimes gives it that afterschool special feel of propaganda – of knowing that someone had an idea in mind before they started writing, and went looking for only the worst evidence in service of that idea. I’m not particularly nostalgic for the 90’s or the 00’s, but I do think there exists a desire in every generation to look back on what came before, and reassure themselves that things are better now. I also think, on the whole, that they probably are, though living through the Trump Presidency, and observing the extreme alienation we’re all continuing to inflict upon ourselves via our various screens and feeds, I definitely wonder sometimes what “better” really means.

And if I’m being really honest (and I swear, I’m trying to be), a not-insignificant part of me is guilty of the same confirmation bias approach of which I just accused Kazemi – of setting out to write this article, this way, before I even read the first page of new millennium boyz (blame that bait-y front cover blurb). This book was literally designed to push buttons. I so wanted to hate it, and much like the boyz themselves, it seemed to want me to hate it too – if only to free it from the overwhelming burden of expectation. And yet, in a move that will likely please no one, I came down pretty squarely in the middle. I went in suspecting it was written in bad faith – that the entire thing was a troll (and that Bret Easton Ellis was working an even deeper troll by attaching his name to it) – but I came away feeling very much the opposite. Or at least, feeling a lot of opposite things at once. I personally didn’t like the shortchanging of the female characters, but Kazemi does a pretty decent job of defending that decision when asked. The ending did not work for me, but I can certainly understand its dramatic impulse. If the book doesn’t quite land with the scathing, satirical force of a FIGHT CLUB or an AMERICAN PSYCHO, it’s only because it seems to want a level of sympathy for its characters that they neither earn, nor deserve. Patrick Bateman’s confessions, by his own admission, ultimately “meant nothing,” but Kazemi seems hell-bent on his characters’ meaning something. Meaning anything in a world supposedly devoid of authentic meaning. Because of this, as its overwrought final chapters all but scream in solidarity with its protagonists that anyone who isn’t suicidal or psychotic is completely full of shit, new millennium boyz struck me as, strangely, a little bit too sincere.

(All that said, I won’t pretend for a minute that I don’t have blind spots of my own, or that anyone, Kazemi included, couldn’t pick up my book tomorrow and find plenty of similarly subjective, sociocultural bones to pick at. I would honestly welcome that. Dark humor is tricky – the darker the trickier – but great satire should strive, first and foremost, to start conversations, not be their final word.)

I’ve touched a lot over my past few years writing reviews on the arguments, pro and con, around separating the art from the artist, and I always come back to a pretty simple maxim: “we all make choices, so don’t judge.” I feel confident there are people – maybe even people in my immediate circle of online literary friends – who won’t like that I spent a week reading this book and another week+ of my time and energy thinking and writing about it. But here we are. I still listen to Michael Jackson. At Alice Glass’s public request, I’ve bid a sad farewell to Crystal Castles. I will rewatch CHINATOWN before the year is out. I haven’t watched MANHATTAN since… well, you know since when. Whatever trouble they caused, the new millennium boyz team didn’t do anything to warrant my dismissing them out of hand. I know great reviewers who feel otherwise (and if anyone comes around pestering me to pull this review, I’ll be the first to change my tune), and I fully respect their decisions not to contribute their attention to this particular economy. Kazemi and company have made it hard to completely separate them from this book, but I’ve tried to judge it on its own merits, such as they are. What I found was literarily uneven, but artistically fascinating, and all the attendant hubbub has, for me, only highlighted the contradictions inherent to a “transgressive literary community” that celebrates assholes like Bukowski, and Burroughs, and Mailer, but still gets up in arms over blurbs and book deals and breaches of internet decorum. We love our rule breakers, it seems, but only when the rules they break aren’t our own.

We all make choices.

Don’t judge.

In closing, as the unwieldy breadth of this article might suggest, new millennium boyz has been infinitely more fun to think and write about than it was to read. I couldn’t help but chuckle when Lit Reactor interviewer Gabriel Hart referred to it as an “endurance piece,” and nod my head in solidarity when Bookstagrammer @BlueboyBookClub suggested the entire thing was some kind of performance art. These strike me as pretty sound accusations. As I said in the intro, there’s been a lot of chatter about both its “dangerous” content, and its “fuck the rules” marketing, and I think all of that was entirely by design. The Anarchist’s Cookbook is dangerous. The Secret and The Game and The 48 Laws of Power are dangerous. The Bible is dangerous. This book is not dangerous. Kazemi has said as much himself. He fought the trigger warning and lost. I suspect if he’d had his way, the n-words wouldn’t be *****ed out either (an especially odd move alongside copious other uncensored racial slurs). These are the decisions of a Big 5 publisher worried about its bottom line, not an indie lit provocateur. I don’t believe writing a “dangerous” book was ever even his goal. But publicly toying with the idea of a “dangerous” book through our present media landscape? Maybe, maybe. As Lu himself notes, in one of the book’s defining quips, “Rumors are always so much more fun than the truth and, you know, the best place nowadays to start rumors is on the internet.”

By the same token, the internet of today is virtually unrecognizable as compared to the internet Lu, Shane, and Brad are dialed into back at the turn of the millennium. We live in a time when Redditors can gang up and hack the stock market, and K-Pop fans will occasionally band together to swing an election. It’s not the wild west anymore. It’s a teeming civilization; a manipulable, and predictably reactive body politic. To think that any marketing team – and especially the marketing team for this book – didn’t understand that, and set out to play a little 3-dimensional chess with all our jealousy and self-righteous outrage, is willfully naïve. Pissing off indie lit Twitter was undoubtedly a calculated move – or at least one they were fully prepared to exploit to their advantage – and I hate to admit it, but they got us. The second we all started talking about them, complaining about them, and oh-so-embarrassingly caring about them, they got us. And who knows? Maybe I’m giving them too much credit, but I for one will remember new millennium boyz forever, and in that way, it is an unqualified success. Its place in the zeitgeist of 2023 is secure. But to say it’s great literature is missing the point. To say it’s vapid and vile is missing it even more. From the very beginning, trying to write anything about it felt like a trap. Whatever we said, good or bad, would only be playing into their hands; either calling out, or participating in the corporate counterculture machine. I’m part of it for writing this. If you’re reading it, you’re part of it too. Brad, Lu, and Shane are part of it now as well. On some level, they knew all along. And that, more than anything, is the point.

Tags: Alex Kazemi, Books, Bret Easton Ellis, Chuck Palahniuk, Fight Club, Lost Chldren, New Millenium Boyz, Permuted Press, Simon and Schuster, Troll, Whiskey Tit Books

No Comments