Does this look familiar? Of course it does.

While THE CABIN IN THE WOODS received something of a mixed reception? upon arrival— some critics adore it, others find it too clever for its own good at best and pointlessly self-reflexive at worst — what is surprisingly lacking in many reviews is the simple recognition of the film for what it actually is. It is not a simple SCREAM-styled commentary on the tired clichés that are firmly planted in the roots of horror cinema. THE CABIN IN THE WOODS is a call to arms. This film is co-writers Joss Whedon and Drew Goddard telling horror audiences that they should expect something more, and telling horror filmmakers that it’s time to start delivering something better.

Much of the most severe criticism of THE CABIN IN THE WOODS aims at the fact that the film is too much of what it is targeting. This line of critique assumes THE CABIN IN THE WOODS to be, in the end, exactly what the critic assumes the film is poking fun at — the “teenagers in the woods” horror film. It’s a plot that has been used by countless horror films dating back at least to Kåre Bergstrøm’s 1958 Norwegian thriller De dødes tjern (aka LAKE OF THE DEAD), in which a group of friends go on a weekend retreat at a secluded mountain spot and find themselves involved in strange, possibly supernatural happenings. While LAKE OF THE DEAD is paced more like Bergman than, say, its Hammer contemporaries, it is easy to see LAKE OF THE DEAD as an early prototype of such films as EQUINOX (1970) and what is perhaps the ultimate “cabin in the woods” horror film, THE EVIL DEAD (1981). In order to offer a critique of this “standard issue” horror film, THE CABIN IN THE WOODS is obliged to actually be one of them on some level.

In other words, if THE CABIN IN THE WOODS took place entirely in the sinister corporate offices where its evil puppet masters punch the clock, what could it really tell us about the horror films it is patterned after? There is one thing that the film points out that is utterly unavoidable: this hoary old setup is, even after countless permutations, still absolutely capable of working on the audience when done skillfully. If the scenes of remote manipulation had been removed, THE CABIN IN THE WOODS would still be a serviceable little horror film. There is comfort in its easy characterization, even though the characters themselves are not entirely comfortable with the parts they must play. The audience is given the characters it expects to see, and that’s the point. If we didn’t get them, we’d feel cheated. Whedon and Goddard go out of their way to fulfill the standards of the “stranded in the forest” horror film, and then point out both why they work and why they are ridiculous.

Why they work: Darkness and nature are scary because they represent the unknown, and things that man cannot control. These are the sort of lizard-brain, caveman fears that underlie every “cabin in the woods” horror film, which Lars von Trier took to harrowing extremes in ANTICHRIST (2009). In that film, von Trier observes that “Nature is Satan’s church,” a place where “chaos reigns.” Send any group of people out into the deepest, most remote part of any forest with the most sophisticated technology to help make them comfortable, and someone will still get totally freaked when the lights go out. The “cabin in the woods” horror film trope always plays on this basic fear, that something is lurking in the dark that cannot be controlled, cannot be understood, and that wants to kill us. Even the most basic horror film can get this right without too much difficulty, because we will always be afraid of the unknown.

The familiar characters of the American horror film have evolved over many years into the stock roles described in THE CABIN IN THE WOODS. These have mostly been defined in terms recognizable to high schoolers or other young people who are still very much in the midst of the rigidly-defined social structures of youth culture. This is, simply enough, because horror films have traditionally been aimed at young people. From I WAS A TEENAGE WEREWOLF (1958) to FRIDAY THE 13TH (1980) on through to the FINAL DESTINATION series, young characters (often students) have acted as the protagonists of horror films and served as these films’ primary audience. Many horror films freely mix characters who would generally never be caught dead with each other in a real high school, and would often offer (typically weak) exposition to explain just how the Jock, the Whore, the Virgin, the Nerd and the Stoner might all end up together on a weekend getaway. When done well, the audience can relate to the disparate group even though it seems odd that they’re all hanging out together — see, in particular, any of the first four FRIDAY THE 13TH films for examples of how this looks when it works best.

In other words, the easily defined, one-dimensional characters are shorthand for all the people the young audience actually knows. They may have direct one-to-one relations with actual classmates, or they may be approximations, but they are easy to hook into and understand. The fact that these films often put characters together who would not spend time together socially creates a pleasant illusion of a social utopia that the young audience members may like to imagine actually exists, although they know it is extremely unlikely.

Which is exactly why they’re ridiculous.

Why they’re ridiculous: “We are not who we are,” observes Marty (Fran Kranz), the Stoner, at a crucial point in THE CABIN IN THE WOODS. When we are introduced to the characters at the start of the film, they do not clearly fall into the roles which they will eventually fill as they are manipulated by the men at the control panel. Dana (Kristen Connolly) is moping around, mulling over a sexual relationship with a professor that has ended badly. Her friend Jules (Anna Hutchison) is taking Dana on a weekend trip with Marty, Jules’s boyfriend Curt (Chris Hemsworth) and Curt’s friend Holden (Jesse Williams). The characters’ definition and their relationships with each other are muddled at first. Dana and Curt have an obvious attraction to each other, and Curt is not a simple jock. Holden actually appears to fill this role at first, stopping in the middle of the road to catch Curt’s errant football pass. Marty’s relationship to the rest of the group is not at all clear until much later.

As the film continues, each character starts to exhibit behavior based on the archetype they are destined to play. Dana is an intelligent young woman comfortable with her own sexuality, but later in the evening she finds herself saying “I’ve never done this” when she makes out with Holden. Curt becomes more and more dense and single-minded, until he is nothing more than a walking hard-on. Jules becomes Curt’s female counterpart, flirting hard with everyone else in the cabin. And Holden inexplicably becomes the Scholar, although exactly how seems more out of obligation than anything else, which makes sense given the explanation at the end of the film. When Dana learns she played the role of the Virgin, she scoffs. “We work with what we’ve got,” explains the Director (Sigourney Weaver in a brilliant cameo). Dana doesn’t fit her role any better than her friends fit theirs.

This is why these immediately familiar characters are ridiculous: no real person fits so neatly into these slots. We recognize them as stock roles, but they are stock roles that we have come to expect to see. The horror audience has been conditioned to pick up a few cues and know who these characters are, and it works every time. However, at the same time, we understand that these are not real people. They are caricatures of people we may believe we know or have known. They are shorthand versions of real people. Marty sees the change in everyone’s behavior and understands that they are being whittled down from their messy, complicated selves to something easier to understand and control.

This latter point is even explicitly underlined by Hadley (Bradley Whitford) when he observes that he knows the Virgin has to go through this ordeal, that she has to suffer, but he finds himself pulling for her to survive. The audience should feel the same way about the heroine of a good horror film, even though they realize she is not a “real” person and that her fate is ultimately inconsequential. Hadley points this out when he interrupts his observation mid-sentence when the party arrives to exclaim “TEQUILA IS MY LADY!” What happens to these quickly-sketched characters, ready-made to fit into audience expectations, really doesn’t matter in the end. They are not “real,” they are off-the-shelf parts, made to plug into any number of horror-film situations and play out their stories. If they were not ridiculous, we could not allow them to be so disposable. We may momentarily care about what happens to them, but as soon as the credits roll or we turn the TV off, it doesn’t matter any more.

As for the primal human terror of the dark, THE CABIN IN THE WOODS again makes an obvious case for this being a totally irrational fear. Technology has advanced to the point where man can control the darkness, even perhaps control those things in the dark that we are afraid of without knowing exactly what it is that we fear. The things we cannot name in the dark can be captured, catalogued and named. We may find ourselves unsettled when left alone in the dark, but we know that this fear is ridiculous. We know that we can turn the lights back on; we can pack up the car and head back to civilization. We go to the movies and we find these familiar characters and we are comfortable in our seats. We watch them make bad decisions and suffer the inevitable consequences, and we go home safe in the knowledge that, should we ever find ourselves in the same situations, we will know better. We have had our cathartic experience through the characters, in which we have gone into the dark and come out alive.

What makes THE CABIN IN THE WOODS such a successful critique of the horror film is that it acknowledges all this — including the fact that it works– and pointedly states that it is time to leave these things behind. Dana is given a choice at the end of the film: kill Marty, survive and fulfill her role as the Final Girl, and appease the dark gods who demanded her suffering in the first place. Or let Marty live, fail to fulfill her role to the note, and the world will end. Thanks to a combination of luck and circumstance, Dana spares Marty and the two share a joint as the sun comes up and the Old Gods return to rule over the Earth. “Maybe it’s time to give someone else a chance,” Dana reflects. The film ends with the literal destruction of the cabin in the woods, a symbolic gesture that also acts as the end of the “cabin in the woods” horror trope. Every monster imaginable has terrorized generations of teenagers at that cabin, and now something unimaginable must take their place.

Many critics have read the Old Gods as us, the viewing audience, demanding that each part be played exactly as expected and damning any variation as a failure. But it makes more sense that the Old Gods are those things that lurk under the surface of horror cinema. When we watch a horror film and get what we expect, we may get some “scares,” but in the end we may feel we have overcome some fear. But what fear do we overcome by watching someone else suffer? Why are some viewers made so deeply uncomfortable when presented with the unexpected and the unusual? These are the things that we are truly afraid of, the things that we cannot name. Any time a film confounds our expectations, it chips away at those surface fears and gives us a glimpse of something beneath, and that is truly unsettling.

Further, THE CABIN IN THE WOODS suggests that these deeper fears are universal, and that the horror cinema of other countries– most notably Japan, in some of the film’s funniest moments– is growing similarly stagnant. Japan’s long-haired ghost girl, once a frightening icon of unknown horrors, is now so familiar and robbed of its iconic power that it can be defeated by a classroom of smiling third-graders. Every culture has its own demons that it uses to safely exorcise its fears through the cinema, but after we see them so often they lose their danger. They become comfortable. THE CABIN IN THE WOODS recognizes this fact as a major failing in the horror genre.

Why do we have to wait until we’ve done a story to death to come up with something new? Why do we have to keep coming back to see the same things happening to the same characters over and over again? When do we finally draw the line where we’ve seen our last group of teenagers at our last cabin in the woods being knocked off by our last flesh-hungry zombies?

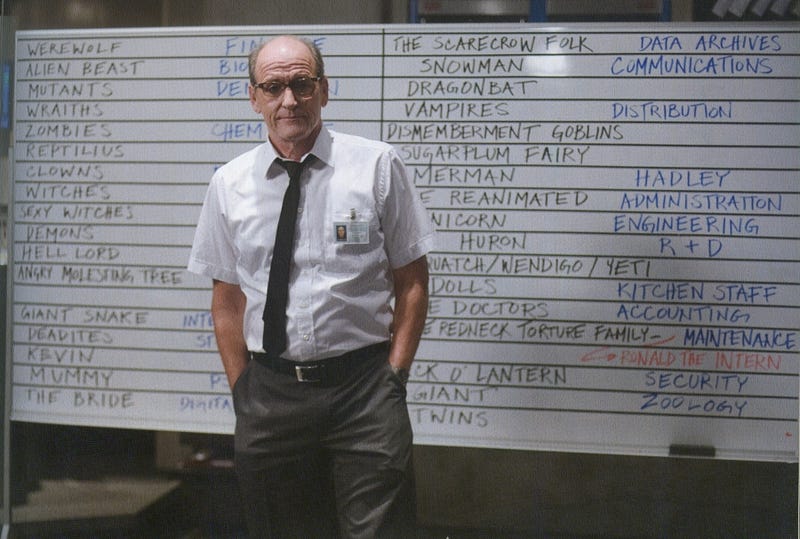

The answer to that last question is “now.” It’s time to stop sending those kids to die in the mountains. It’s time to stop offering them up to “Werewolves,” “Witches,” “Sexy Witches,” “Angry Molesting Trees,” “The Scarecrow Folk,” “Sasquatch/Wendigo/Yeti,” and especially the “Zombie Redneck Torture Family” (among others listed on the film’s infamous whiteboard). It’s time to give some new characters, real characters, to some new creatures or fates as yet unimagined. It’s time to stop leaning on what works and try something new. As anyone who has done exactly that knows, there are few things more scary. That is the challenge issued by THE CABIN IN THE WOODS. Hopefully horror fans and filmmakers are ready to take it.

Time to put these things to bed.

- [CINEPOCALYPSE 2017] FIVE FILMS YOU CAN’T MISS AT CINEPOCALYPSE! - October 31, 2017

- Hop into Jason’s Ride for a Look at the Wild World of Vansploitation! - August 11, 2014

Tags: Anna Hutchison, Bradley Whitford, Chris Hemsworth, Drew Goddard, Horror, Jesse Williams, Joss Whedon, Kristen Connolly, Kåre Bergstrøm, Richard Jenkins, sigourney weaver

No Comments