OK, stop me if you’ve heard this one before: There’s a pair of identical twins (or siblings or cousins or clones or pod people or even just some lookalike randos) and one takes over the other’s life for some purpose, nefarious or not. Maybe it’s to inherit money from a dead relative or to escape the law or to escape the confines of the palace or something much more mundane. It’s been done roughly a gazillion times in films and TV episodes because it’s a great hook for a story that digs into some basic questions: What makes us us? If we were to switch places with a doppelganger, would it matter? Would the experience change either of us? Would anyone even notice?

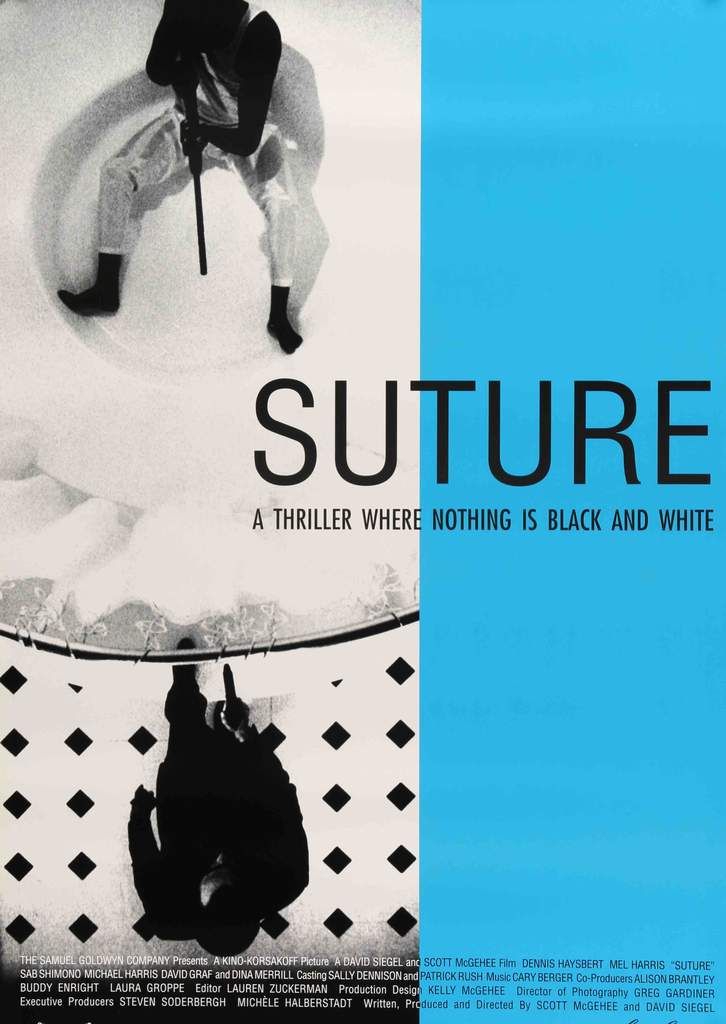

The 1993 neo–film noir feature SUTURE takes that basic, well-worn concept and then twists it into something wholly original. Co-writers and co-directors Scott McGehee and David Siegel start by taking the basic idea but then add a wrinkle. And by a wrinkle, I mean a mountain — one that some viewers might have trouble getting over. (I will admit I had some trouble with the film’s central conceit when I first saw it on video in 1994 or so.) Oh, and beware: There are major spoilers beyond this point because the film can’t really be discussed without them.

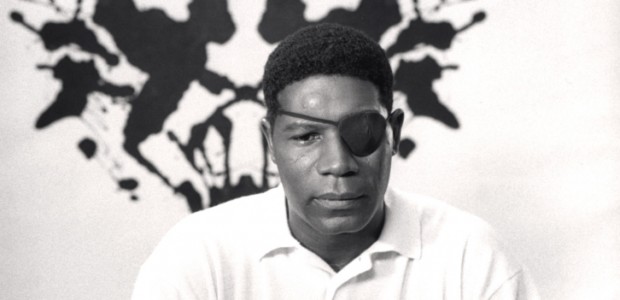

The “twins” in SUTURE — in this case, they are identical half-siblings, just recently discovering each other’s existence at the film’s start, after spotting each other at their father’s out-of-town funeral—look absolutely nothing alike to the viewer. In fact, Clay, who grew up with modest means, away from his wealthy father, is played by a black actor (Dennis Haysbert, probably best known as the president on 24); the wealthy Vincent is portrayed by a white actor (Michael Harris, probably best known … well, for SUTURE, I guess, but he does have the intriguing credit “Naked Man Smoking” in something called OTHER VOICES). There are literally no conditions under which these two human beings could be mistaken for each other in real life. But in the world of SUTURE, they are 100% indistinguishable. And so begins a tangle of lies, patricide, attempted murder, amnesia, and mistaken identity. Underlying it all is the subtext of race.

“How is it that we know who we are? We might wake up in the night, disoriented, and wonder where we are. We may have forgotten where the window or the door or the bathroom is, or who was sleeping beside us. We may think, perhaps, that we have lived through what we just dreamed of. Or we may wonder if we are now still dreaming. But we never wonder who we are. However confused we might be about every other particular of our existence, we always know that it is us, that we are now who we have always been.” —Dr. Max Shinoda (played by Sab Shimono)

Clay arrives in Phoenix by bus and is greeted at the station by Vincent. Although Clay is there on his half-brother’s invitation, Vincent seems overtly hostile and suspicious. Clay protests that he’s not after any part of the family fortune — he just wants to get to know his half-brother. After all, they share “common blood,” as Clay puts it. Vincent has reason to seem stressed out, though; he has a lot more on his mind than just a possible gold-digging relative who’s popped out of the woodwork. That funeral for his father? The old man is dead after being shot, and Vincent, a competitive sharpshooter, is under suspicion by the police for his murder.

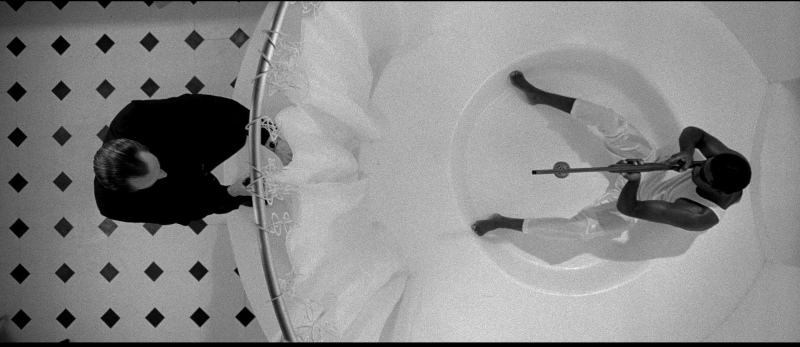

Vincent does a quick makeover for a reluctant Clay, dressing him in an all-white suit that matches his own, and asks Clay to drive him to the airport. But it’s a setup — Vincent is leaving the city under an assumed name, and he’s installed a bomb in the car to kill Clay as he drives back to Vincent’s home. Because no one else knows about the identical brother and Clay is wearing the white suit Vincent is known for favoring, Vincent assumes the authorities will think the dead body in the car is his, and he’ll be off the hook for his father’s murder. Unfortunately for Vincent, Clay doesn’t die; and unfortunately for Clay, he wakes up with complete amnesia.

And so begins Clay’s struggle with his identity. Everyone believes Clay is Vincent, and so project their assumptions on to this tabula rasa. Clay attempts to slide into Vincent’s identity—going shooting, for instance, with his plastic surgeon and love interest, Dr. Renee Descarte (!) (played by thirtysomething’s Mel Harris), and listening to Vincent’s beloved operas. But the persona is a poor fit for Clay, who begins getting flashes of his old life in dreams, which disturb him greatly (and which reminded me of the Dali-designed dreams in SPELLBOUND). Eventually, Clay must confront his brother for the right to continue living a life of (white) privilege.

“Each man has his own jungle. It’s just a matter of understanding it and knowing where one fits in—knowing who are the scavengers and who are the predators.” —Vincent

SUTURE sometimes feels like two different movies that happen to be unspooling at the same time. One is pure film noir, and the script could have been shot with two actors of the same race in the leads and felt quite at home in the 1940s or ’50s with few revisions. And the other is an examination of race and class in America and how they shape the destinies of black and white citizens (and poor and rich and scavengers and predators) differently. The combination is quite unique, to my mind, as well as bracing and powerful. I liked the film when I saw it back in the ’90s (though, as mentioned earlier, I struggled a bit with the idea of nonidentical identical twins); now, though, it seems to me to be an unheralded indie classic.

Director of photography Greg Gardiner (he most recently shot last year’s comedy hit GIRLS TRIP) does amazing work with his (of course) black and white cinematography. Most of the cast is terrific — Haysbert especially. Not that Michael Harris is bad as Vincent, but it’s a much less-nuanced performance. Dina Merrill adds some old-Hollywood glamour as a family friend, and reliable character actor David Graf plays a memorable policeman, Lt. Weisman.

The recent widescreen remaster really makes this film shine — that pan-and-scan VHS transfer I saw decades ago was not nearly as transporting. It’s available on Blu-ray from Arrow Video (featuring a commentary by the writer-directors and interviews with a number of people involved, both from in front of and behind the camera); it’s also streaming in high-definition on Amazon Prime.

Tags: Amazon Prime, arrow video, Blu-ray, David Graf, David Siegel, Dennis Haysbert, Dina Merrill, Fran Ryan, Greg Gardiner, John Ingle, Mel Harris, Michael Harris, Neo-Noir, Sab Shimono, Scott McGehee, Steven Soderbergh

No Comments