When fringe characters become a part of the pop-culture mainstream, the danger is that people can forget what makes them unique. This is how a billion dollars gets netted by a Batman movie where Bruce Wayne quits being Batman. (Twice!) Batman doesn’t quit, you dopes. Batman never quits. Superman might consider it, and Spider-Man might consider it, but not Batman, not ever. That’s what makes Batman interesting as a character. If you want to make a movie about a guy who gives up the cape and cowl for a happy ending, you don’t choose Batman, of all superheroes, to star in it.

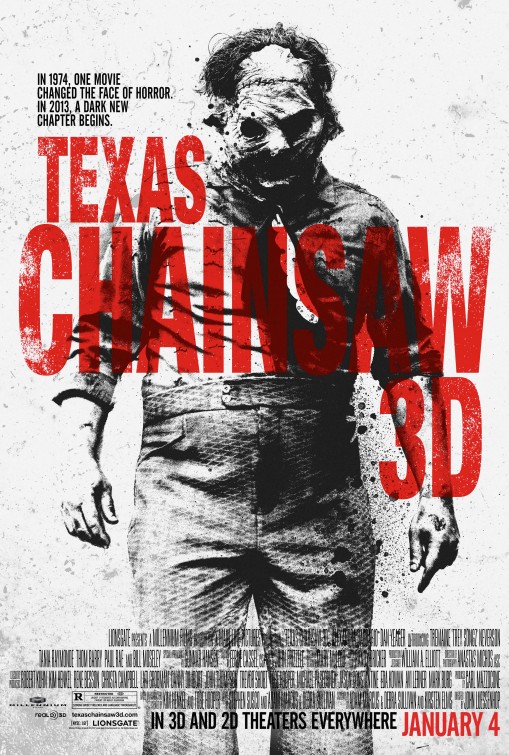

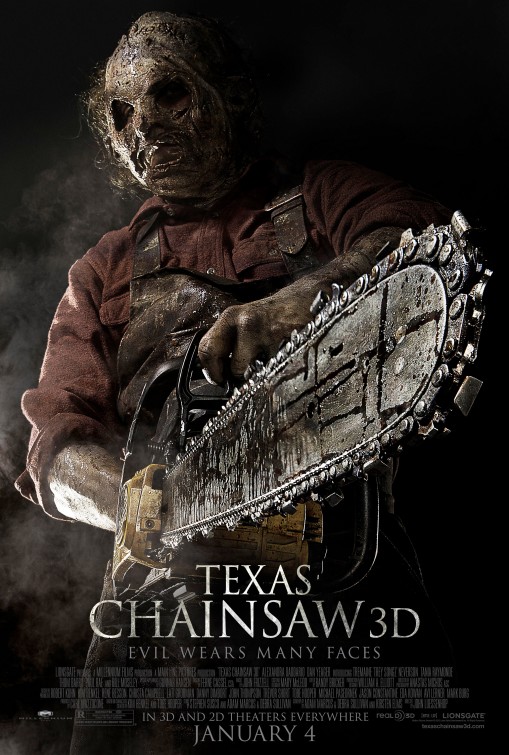

And in much the same way, TEXAS CHAINSAW misunderstands its source material, even as it races around frantically trying to reference and pay tribute to it. If you want to make a routine slasher movie, you don’t turn to 1974’s THE TEXAS CHAIN SAW MASSACRE, which is a genuinely important American film, but not for the reasons the makers of 2013’s TEXAS CHAINSAW 3D seem to think it is. Let’s talk about the original for a minute, before ripping into its purported update.

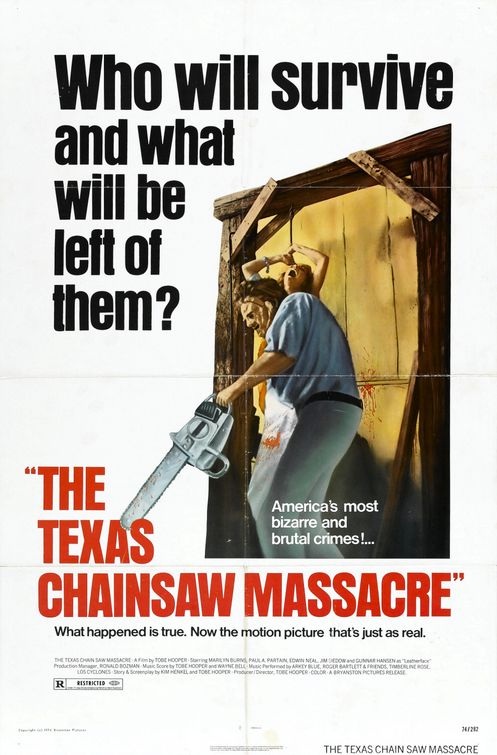

THE TEXAS CHAINSAW MASSACRE was a movie of its time, and it reflected that as surely as any other more prestigious and acclaimed American classic. Movies of the era like THE GODFATHER, TAXI DRIVER, ONE FLEW OVER THE CUCKOO’S NEST, and A CLOCKWORK ORANGE are justly heralded, but THE TEXAS CHAINSAW MASSACRE is equally important as a historical document of the 1970s. The movie arrived in 1974. This was the era of the Vietnam War. The war was still going on when the movie was being made. What director Tobe Hooper and his collaborators did was to capture the anger of the era, obviously without addressing it directly in the story, but most certainly with the ferocious, hopeless atmosphere of the piece.

Five years before THE DEER HUNTER or APOCALYPSE NOW, THE TEXAS CHAINSAW MASSACRE managed to reflect the cultural unease, disillusionment, and nihilism that the war in Vietnam by all accounts engendered in American minds. Note how iconic franchise villain Leatherface carries a chainsaw as his weapon of choice. The chainsaw treats human bodies like inanimate objects – like meat. The chainsaw is more businesslike, less up-close-and-personal than say, the fangs of Count Dracula, or even the knife wielded by Michael Myers. The house where Leatherface dispatches most of his victims is literally a slaughterhouse. Meat lockers line the walls. Bones decorate the setting.

Horror audiences have become inured to this kind of imagery but in 1974, it had significance. Human bodies treated like cattle, hung by meat hooks and clubbed in the head with ruthless efficiency. It’s an impersonal, industrial kind of murder. When the movie does demand an emotional response to the murders, it does so in unusual, script-flipping sorts of ways. Think of Franklin, the wheelchair-bound character – sure he’s disabled but he’s also one of the most intolerable creatures in film history. This is a type which movies normally sentimentalize, yet Franklin is so abhorrent that, if anyone, most audiences end up siding with Leatherface by the time Franklin is sent to his fate. As the film progresses, the murders are purged of sentiment.

People are just meat, ground up by an unintelligible enemy that cannot be reasoned with or dissuaded. Now think again of the Vietnam War. In general terms, the first sentence of this paragraph could be describing the actions of a murderous giant carrying a chainsaw, or that of a lengthy and unpopular overseas conflict which tore apart many American lives. How much of this thematic resonance was intentional and how much was intuitive does not matter as much as the fact that it IS resonant.

What an opportunity, then, for a horror movie released in 2013, to address some comparable sociopolitical subtext. Again America is embroiled in an unpopular war overseas. Unlike the era of the Vietnam War, however, many Americans are not concerned with the details of our current war on a daily basis. Modern war affects some of us profoundly and many of us hardly at all. This is very fertile ground for the kind of veiled commentary and brutal satire which is buried within so many of the great horror films.

It may yet happen. It won’t be TEXAS CHAINSAW 3D to do it. Most of the superficial elements that defined the original film are in there, but the underneath is hollow. These bones ain’t got no meat on ‘em.

TEXAS CHAINSAW 3D begins promisingly, by kicking off with a rehash of the original film, emphasizing its most brutal moments. Sure, we’re just looking at clips from a movie most of us have seen before, but we’re looking at them in 3-D, which does give an engaging novelty to the familiar, while also giving the whole thing as close to an old-fashioned drive-in feel as we’re going to get. So we watch souped-up 1974 footage as Leatherface and his disturbed family murder a vanful of teens, torment the one survivor, and then chase her off as she barely escapes with her life – all that we know. Like THE KARATE KID: PART II, the new TEXAS CHAINSAW movie picks up right where the original left off, acting as a direct continuation of those infamous events.

What complicates matters, of course, is that TEXAS CHAINSAW 3D is not the first movie aiming to serve as a follow-up to THE TEXAS CHAINSAW MASSACRE. I’m far from an expert on this property and I’m sure my colleagues and readers can ferociously enlighten me if need be, but here’s my best version of a roll call:

There was THE TEXAS CHAIN SAW MASSACRE, which we’ve already established. A stone classic.

Twelve years later, there was Tobe Hooper’s own THE TEXAS CHAINSAW MASSACRE 2, which introduced new members of Leatherface’s family, now known as the Sawyers, including fan-favorite character Chop Top (Bill Moseley). As far as I can tell, this film is generally considered part of the canon.

Four years later, there was LEATHERFACE: THE TEXAS CHAINSAW MASSACRE 3 – a reboot – with contributions from the terrific writer David J. Schow, the pioneering KNB Effects Group, the legendary Ken Foree, and a young Viggo Mortensen — all of that, yet no involvement from Tobe Hooper.

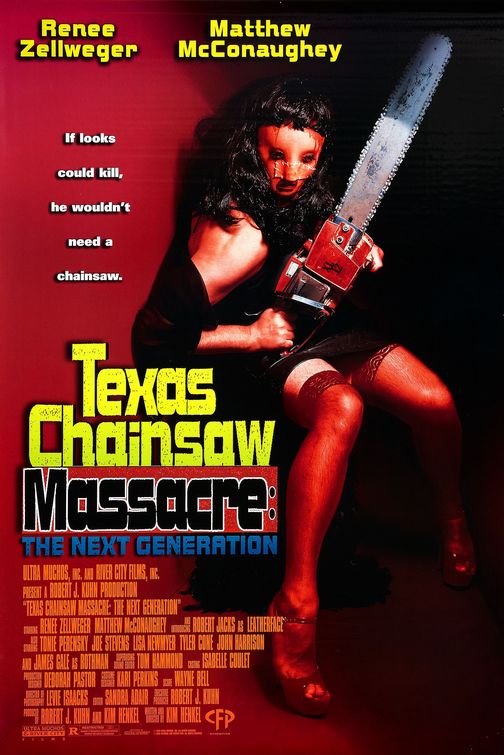

Another four years later, there was TEXAS CHAINSAW MASSACRE: THE NEXT GENERATION, written and directed by Hooper’s original co-writer Kim Henkel. This was essentially a remake of the 1974 film, but again, no Tobe Hooper. Whether for that reason or for several others, it’s not a very popular entry in the series. This is the one Matthew McConaughey and Renee Zellweger would rather we forget.

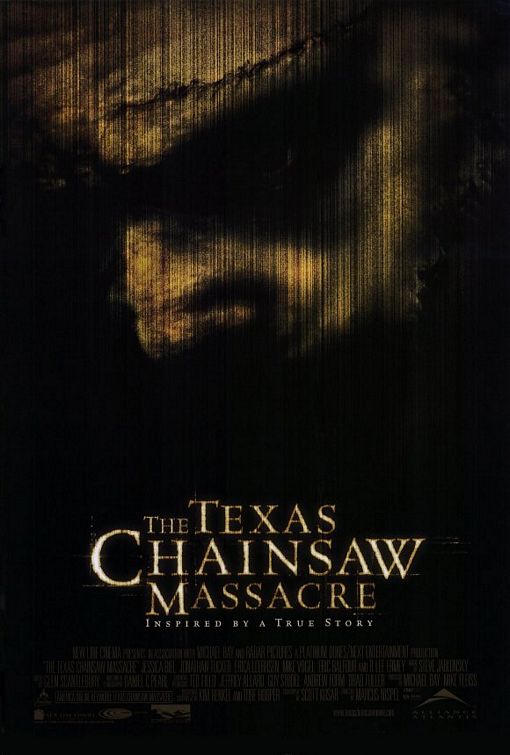

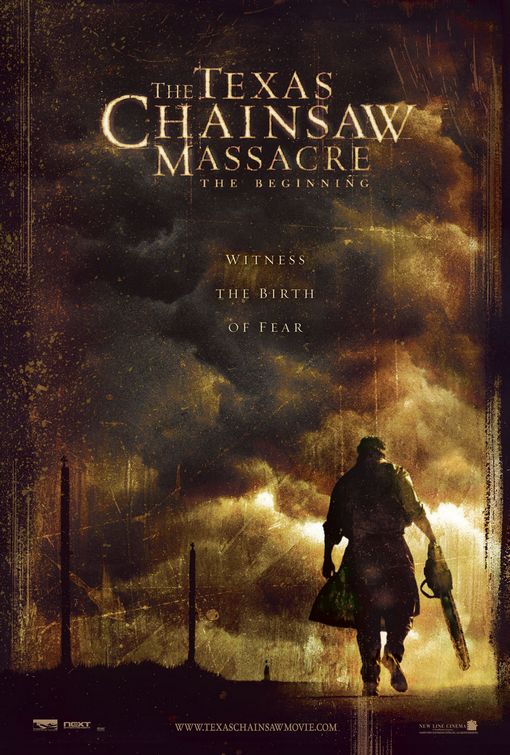

And finally, there were the two TEXAS CHAINSAW movies produced in 2003 and 2006 by Michael Bay’s company, Platinum Dunes. One was meant as a remake of the original film, and one was a prequel to that remake. (Confused yet? I sure am.) Tobe Hooper and Kim Henkel both received producers’ credits on these two films, but by now we have adequate call for concern. The Platinum Dunes movies have their defenders, but it’d be hard to argue that these movies have much more on their minds than pretty photography capturing viciously ugly things happening to very pretty people. If you like that, fine, but again, metaphorically speaking, it’s the same as Batman quitting. What made the original TEXAS CHAIN SAW special was its grimy unpredictability and its surprising restraint. You can’t make this shit pretty. Well, you can, but you’d be wrong to do it.

Now.

The early sequences of TEXAS CHAINSAW 3D, picking up after directly the end of the 1974 film, shows a local sheriff (Thom Barry, a good candidate to play Al Roker in the inevitable biopic) driving up to the Sawyer estate. He’s investigating the claims made by a hysterical young girl that her friends were slaughtered at the house. He finds the entire Sawyer clan holed up in the house, refusing to come out. It’s a standoff. By beginning the way it does, TEXAS CHAINSAW 3D attempts to clear through the clutter but it actually complicates things somewhat. We recognize some of the faces, but there are plenty of new ones, and also, some of the recognizable faces are playing different characters! Grandpa is there. Leatherface is there. Maybe a bit confusingly to longtime fans (and to those like me with a passing familiarity with the franchise) Gunnar Hansen, the original Leatherface, is there – playing a new Sawyer the credits list as “Boss.” Bill Moseley is there, but instead of playing Chop Top, he’s playing Drayton Sawyer, Leatherface’s father, who in Hooper’s films had been played by a different actor. (To be fair, maybe this isn’t confusing at all if you’re coming into the franchise fresh. Or if you’re less prone to overthinking than I am.)

Most importantly, one of the Sawyers, Loretta, has an infant daughter. Loretta slips out the back of the house with the girl when the rest of the townspeople, led by redneck shitkicker Burt Hartman (Paul Rae, resembling Jeremy Renner without as intense a workout program), arrive to roust out the Sawyers. The mob turns violent and starts shooting up the house, massacring — presumably — all of the Sawyers. One of the townspeople finds Loretta and kills her, but takes the baby girl to satisfy his wife, who always wanted to be a mother.

A couple decades pass. How many decades is a question that has been rightfully raised by the critics of TEXAS CHAINSAW 3D. (Chronologically it should be four, unless the film is a 1990s period piece.) The baby Sawyer girl grows up and fills out and becomes Alexandra Daddario, an actress who was in a similarly promising-on-paper and similarly disappointing (to me) horror movie called BEREAVEMENT. Here she plays Heather Miller, an unhappy young woman who finds out from her sloppy parents that she was in fact born Edith Sawyer, and heads off to collect on her inheritance. Heather takes a road trip with her boyfriend Ryan (Trey Songz, best known, by people who aren’t me, as an R&B singer), her best friend Nikki (Tania Raymonde, who I recognized from the TV show Lost), and the best friend’s date, Kenny (a spellcheck-killing actor named Keram Malicki-Sánchez). They pick up a studly hitch-hiker named Darryl along the way, and of course hitch-hikers are a bad omen in this franchise.

So far, there’s not much horribly wrong with TEXAS CHAINSAW 3D. Director John Luessenhop, his stable of writers, genre stalwart composer John Frizzell, and cinematographer Anastas Michos, all manage to wring some real suspense out of the early moments, from the time Heather is given the keys to the mansion by her cartoonishly jumpy lawyer (Richard Riehle, ironically the “jump-to-conclusions mat” guy from OFFICE SPACE) to the time that the kids run around the mansion exploring its seemingly empty corridors. I like Alexandra Daddario as a new-breed scream-queen. There have been some nasty cracks about her physique in many reviews (that’s how you can identify the jerks and the creeps), but I like how her inarguable womanliness offsets her youthful looks. There’s believable vulnerability there, which the genre demands, but also believable steeliness, which the script eventually requires of her. The movie has a protagonist worth caring about, and so I’d say in fairness that there’s a solid twenty-minute passage where TEXAS CHAINSAW 3D felt like it was shaping up to be, if not particularly inventive, an effective thriller. It’s when hell breaks loose in the movie that it starts to unravel with a quickness.

Heather, Ryan, Nikki, and Kenny head into town, leaving Darryl behind at the house. We learn some things. We learn that Burt Hartman, the bloodthirsty redneck, is now the mayor. We learn that Sheriff Hooper still holds his office, due to a tenuous alliance with Hartman, and we meet his deputy, Carl, who is Burt’s son. (Carl is played by Scott Eastwood, who in real life is the son of one Clinton Eastwood Jr., and in fact there is a resemblance to the Clint of the early Rawhide days.) We learn that the local police wear jeans with their uniforms, which isn’t a major plot point but I did notice it. And we learn that Darryl is in fact a thief, who stayed behind in order to ransack the house for valuables. While roaming the dark basement, he comes face to Leatherface with Jed Sawyer, the notorious skin-wearing, cross-dressing, mentally-challenged mass-murderer we all knew was coming from a quick glimpse at the poster. Jed has been locked up all these years in the basement like an inmate or a mad dog. He’s Heather’s inheritance, basically, her family responsibility.

So Leatherface kills Darryl. He kills Kenny. He tries to kill Heather. He kills Ryan (which did not go over well with my audience). He tries to kill Nikki. He kills a deputy who comes calling after Heather escapes and alerts the authorities. None of these are spoilers, I don’t think. All these murders happen throughout an increasingly-garbled chain of events. The narrative is trying to keep track of a variety of plots and in so doing, it loosens control over all of them.

There’s a pointless subplot about Ryan cheating on Heather with Nikki, which seems to exist only to justify their deaths, in a gross throwback to they-deserved-it 1980s morality. There’s the ill-defined character of Sheriff Hooper, a seemingly spineless man who lets Burt Hartman run the town, all the way up until the convenient moment where he makes a different choice. There’s the stock villain of Burt Hartman, a one-note character if ever there was one. There’s the anti-surprise of the heroic-looking Carl turning out to be a bad apple off the Burt Hartman tree. (And the fact that Carl seemingly wanders out of the movie – we never do find out what happens to him. Don’t try to tell me it’s because there are plans for a sequel.)

Messiest of all is the central plot of Heather taking her presumed rightful place amongst the Sawyer family. The fact that the movie’s ingénue goes from potential victim to caretaker of a vicious killer might be interesting, if only it meant anything. What – if anything – is this movie trying to say? That Leatherface is harmless compared to Burt Hartman? That somehow the townspeople are the real villains? The townspeople are pigs but they are not entirely wrong – there are monsters in that house. Leatherface is pretty far from his right mind but he’s still killed a lot of people in pretty horrible ways. But once he and Heather discover their family ties they put on the Tom-and-Jerry red bowties and buddy up – her entirely discarding the fact that he slaughtered her boyfriend and best friend. Is the underlying theme meant to be that family may be crazy but family is still family? I hope not. That’s Batman quitting. That’s not what makes this story so powerful. And I’d be drawing that theme out of vague notions hardly explored in the onscreen text, anyway.

Again, the idea that maybe her ordeal awakened some latent familial insanity in Heather could be an intriguing, unsettling idea in a more capably-rendered film. However, the abbreviated way it plays out feels to me more like Stockholm Syndrome, like caving in to that odd, naïve feeling of closeness that some audiences feel for movie killers. Maybe if I love Freddy or Jason or Michael or Leatherface enough, they won’t come for me. When I was a very little kid and I went into the house of horrors at the amusement park, I remember smiling and waving at the creatures that were trying to scare me. On the off chance that those hellbeasts were real, that is not a practical outlook for life.

I keep looking for meaning in TEXAS CHAINSAW 3D where it’s pretty clear there isn’t any. The writing credits list a couple female names. This made me optimistic that the movie might be the rare horror film to have some feminine, feminist energy. It definitely didn’t. Alexandra Daddario is filmed as a sex object, most notably in the final scenes where she is restrained with tape and chained up by her arms, with her shirt torn open in a way that’s meant to torture no one so much as Mr. Skin and all the other undersexed creeps craning their necks for an angle.

Then there’s the fact that Clint Eastwood’s son appears in a pivotal role, appearing to be a savior but then revealing his truer, darker colors. Is the point that heroism is a myth and no one’s coming to save you, particularly not the guy who looks like Clint Eastwood? Nope. That’s me projecting ideas again. (Also, Clint’s son being in TEXAS CHAINSAW 3D leads me to imagine Clint having to sit down to watch TEXAS CHAINSAW 3D, which right there is a more compelling scenario by far than any onscreen.)

Look, I’m not saying that every horror movie needs to come loaded with subtext. Many of the great ones do, but it’s possible to be more ideologically-streamlined and still have the power to frighten. John Carpenter’s HALLOWEEN is a great example of a brilliantly-crafted scare-machine that I don’t think has much thematic depth beyond what people bring to it themselves. But John Carpenter’s THE THING is about something more than scares. William Friedkin’s THE EXORCIST is about something more than scares. And Tobe Hooper’s THE TEXAS CHAIN SAW MASSACRE is about something more than scares. It is my opinion that if you take something meaningful, as the makers of TEXAS CHAINSAW 3D did with THE TEXAS CHAIN SAW MASSACRE, and you strip it of all its meaning (and humor!), without even adding much in the way of craft, then you have wasted my time, and probably your own.

@jonnyabomb

- [THE BIG QUESTION] WHAT’S YOUR FAVORITE FEMALE ENSEMBLE IN MOVIES? - July 22, 2016

- [IN THEATERS NOW] THE BOY (2016) - January 24, 2016

- Cult Movie Mania Releases Lucio Fulci Limited Edition VHS Sets - January 5, 2016

“Again, the idea that maybe her ordeal awakened some latent familial insanity in Heather could be an intriguing, unsettling idea in a more capably-rendered film.”

YES!